Analysis

How Danh Vo Rocketed to Market Stardom With Art Designed to Confound Collectors

As his critically acclaimed exhibition at the Guggenheim winds down, a look into what commerce can teach us about Danh Vo's standing.

As his critically acclaimed exhibition at the Guggenheim winds down, a look into what commerce can teach us about Danh Vo's standing.

Tim Schneider

“Take My Breath Away,” Danh Vo’s critically lauded survey exhibition at New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through May 9, suggests that there’s a fair bit of irony in the artist’s rise to stardom in the contemporary art world. Or perhaps it’s more a matter of poetic justice.

With important exceptions, Vo’s practice largely consists of acquiring and re-presenting objects (sometimes without further alteration) that provide a window into the way culture is shaped. His Guggenheim show, for example, includes pen tips used by President Lyndon Johnson to sign the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which authorized US military force in Southeast Asia—a prelude to the Vietnam War and its irrevocable effects on multiple nations and thousands of lives.

This kind of work doesn’t exactly sound like jet fuel for market stardom. But Vo exploded onto the scene during the art-market boom that began in 2011. A certain subset of his works were immediately devoured by major players, from Qatari art collector Sheikha al-Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani to New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Several years later, Vo has grown into a rare breed in today’s hyper-capitalist art industry: a conceptual artist whose limited forays into mainstream-friendly work have attracted consistent demand among collectors, while the majority of his practice challenges convention and enthralls curators and connoisseurs.

From another perspective, his career offers a case study in how the market—particularly the secondary market—can ultimately offer a distorted picture of an artist’s oeuvre if viewed in isolation.

Installation view: “Danh Vo: Take My Breath Away,” at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Photo: David Heald, ©Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2018.

Vo first came onto the auction market in March 2012. It was an auspicious debut: The work, an early version of the American flag rendered in gold leaf on flattened cardboard, sold for $33,750 against a high estimate of just $7,000. (Note: All figures include buyer’s premiums.) His next four pieces exceeded expectations, too, with prices ranging from 26 percent above the high estimate to more than double.

“It rocketed through the stars within the first consignments,” Cristian Albu, a director and senior specialist in Christie’s postwar and contemporary department in London, said of Vo’s market. “It was like a shot of adrenaline running wild through collectors’ brains.”

The commercial adrenaline peaked in October 2015 at Phillips London, when Vo’s VJ Star (2010) set the artist’s world auction record at over $930,000. (According to a recent profile in the New Yorker, Vo’s most expensive work can demand as much as $1 million on the primary market, although others go for much less. Papers from an ultimately settled lawsuit offer a few additional data points: The collector Bert Kreuk claims that in 2013 he agreed to commission three significant Vo works for $350,000, a figure arrived at by tripling the $125,000 price for a sizable Vo piece in 2012, then applying a discount.)

Vo’s art has now appeared at auction 52 times and generated nearly $9 million in overall sales, per the artnet Price Database. Only 11 of the lots offered were bought in—a 79 percent sell-through rate. Healthy as those headline figures are, they disguise a much more complex relationship between Vo and the overall collecting class.

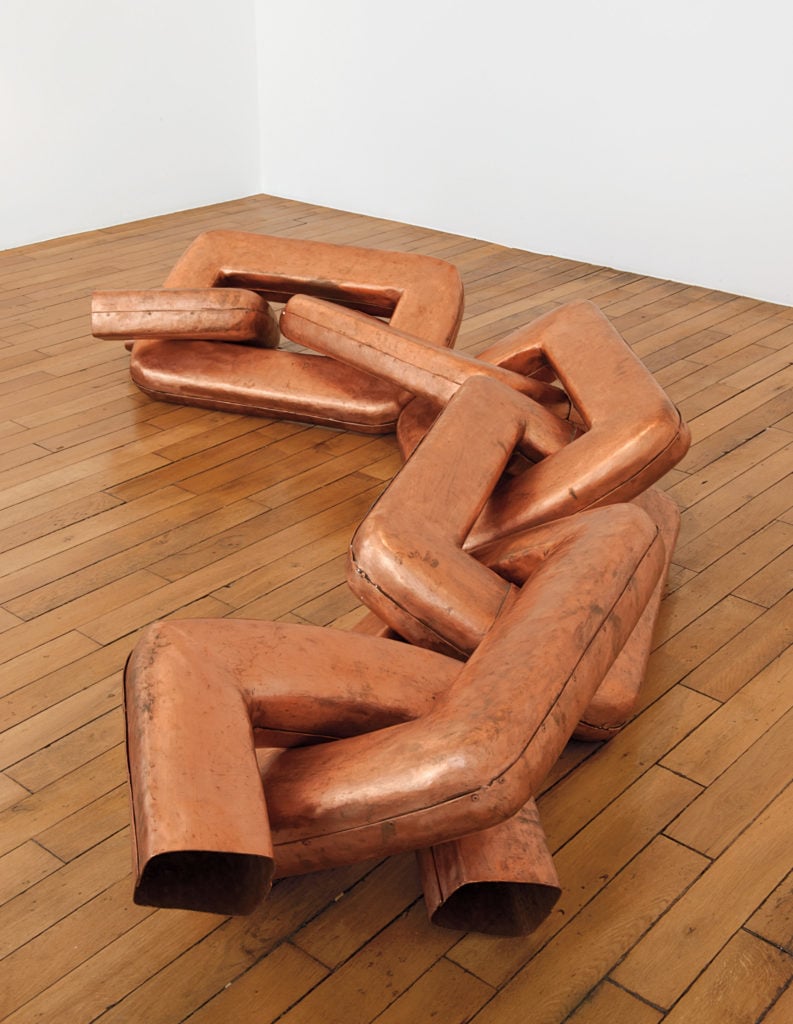

Danh Vo’s We the People (2011). Courtesy of Phillips.

Although the conceptual underpinnings are consistent, Vo’s practice stretches across a variety of materials and forms. However, two bodies of work have emerged as clear favorites in the secondary market.

The first series, titled We the People, consists of more than 300 individual sculptures that, if combined, would create a full-scale replica of the Statue of Liberty. Vo commissioned a foundry in Shanghai to cast the pieces in aluminum, then skin them in a thin layer of copper, just like the (now-oxidized) exterior of Lady Liberty herself.

Some works in the series are instantly legible as representations: fingers, an eye, chain links. Many others, such as segments of the monument’s flowing robes, read merely as abstractions. Aesthetic fluidity becomes a path to symbolic fluidity. As Albu says of the project, “It gave each one of us the opportunity to interpret it differently. It challenged our understanding of freedom and its fragility.”

The highest price paid for a piece in the series at auction is $629,000, set at Phillips contemporary evening sale in November 2014.

Danh Vo’s VJ Star (2010). Courtesy of Phillips.

Another series even more sought-after by collectors, which Vo began in 2009, consists primarily of gold leaf on cardboard. In some of these works, the gold leaf overlays printed logos on shipping boxes for Western products, like Budweiser, that gained a foothold in Southeast Asia. In others, he depicts iterations of the American flag from the era when states were still joining the Union. (VJ Star, his record-setting work, is among these.) Others render individual letters of the Latin alphabet. All bear the weight of history, commerce, and/or colonialism.

The gold leaf works occupied the center of the now-infamous lawsuit between Vo and Kreuk. The collector repeatedly suggested Vo include at least one new gold-leaf-on-cardboard American flag in the fateful commission for a 2013 exhibition of his collection, and sued when Vo only loaned a smaller, existing box. Kreuk, Vo, and Vo’s former gallerist Isabella Bortolozzi settled their various suits and countersuits in 2015.

Vo’s auction history reveals just how much these two series have shaped the public market for his work. To date, 21 of the 23 gold leaf on cardboard works consigned to auction have found buyers, or 91 percent—an even stronger sell-through rate than We the People’s 81 percent. Outside these series, however, only 13 Vo works have appeared at auction. Six were bought in, for a sell-through rate of just 54 percent.

Notably, much of Vo’s other work—like an early performance work where he married, then divorced, two of his friends and appended their last names to his—are far less easily bought and sold.

Installation view: “Danh Vo وادي الحجارة, Museo Jumex, Mexico.” Photo: Abigail Enzaldo and Emilio Bernabé García, courtesy Museo Jumex, Mexico City.

Vo’s loftiest prices at auction have not been among his most recent, which speaks to his career’s broader context and character—as well as the market’s broader evolution in a post-boom era.

As Rebekah Bowling, co-head of Phillips’s contemporary art day sale in New York, notes, Vo’s “highest prices were being achieved between fall of 2014 and fall of 2015.” After that time, “You did see a little bit of a softening [in his market] relative to the softening in the contemporary art market in general.”

As in most other artist’s markets, this activity owes to both the ebb and flow of the wider economy and particularities regarding Vo himself. “There has always been a relatively tight market for the work,” says the art advisor Todd Levin. “Vo isn’t nearly as prolific as some of the other artists of his generation,” but there has been consistent demand. At the same time, “people have seemed to become far more specific and clear about what sorts of works from what bodies of works they would buy.”

In the case of We the People, the “more recognizable” works, such as body parts or chain links, now command higher prices than their abstract counterparts. More free-form pieces from the series sold for roughly $128,000 at Christie’s London last September and $64,000 at Sotheby’s Hong Kong this month. Both went above their respective estimates, but at a fraction of the cost of the $629,000 top seller in 2014.

Danh Vo’s We the People (detail) (2011), so far the highest priced work from the series to sell at auction, at Phillips New York in November 2014. Courtesy of Phillips.

This price dip does not indicate that the artist has lost favor in the art world’s halls of power, however. Vo’s work has been collected by some of the world’s most adventurous and influential buyers, including Thea Westreich Wagner and Ethan Wagner, the Jumex Collection, and the Pinault Collection. As Levin explains, “It’s not that the market has retracted, but that people at first wanted it now, with no regard for economic realities. Now we’re at a slower, more stable secondary market.”

This is not uncommon during periods of exuberance in the art market. When interest on the buy and sell sides coalesces around a young artist, a certain subset of buyers will pay almost any price to be early adopters. But after that eager group has staked its claim, if the artist maintains traction among galleries and institutions, then prices almost always either level off or retract somewhat, while favored bodies of work emerge.

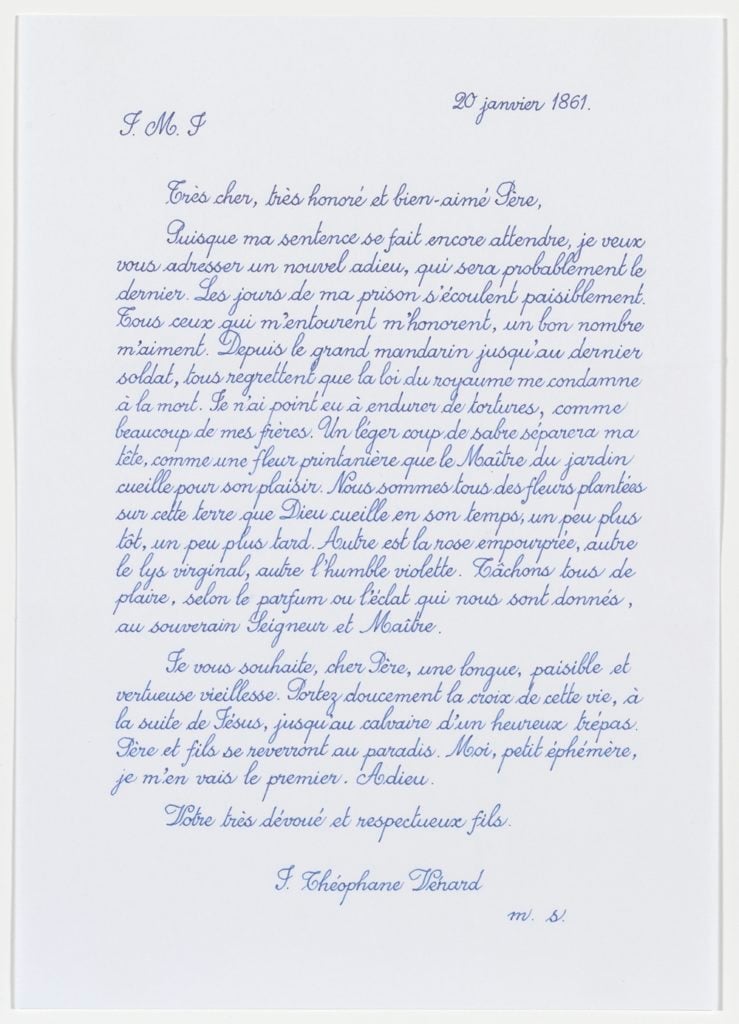

Ironically, however, beyond a few market-friendly series, Vo’s oeuvre seems almost deliberately designed to baffle less connoisseurial buyers. One of his most important pieces is shockingly affordable and effectively unlimited. 2.2.1861 consists of a handwritten copy of a letter by a 19th-century French Catholic missionary named Jean-Théophane Vénard, informing his father of his impending execution for preaching the Gospel in Vietnam. The transcriber is Danh’s father, Phung Vo.

The work is classified as an “open edition” and sells for a scant €300, with proceeds split between Phung, Danh, and the gallery. Vo has claimed that the price will remain constant, and further editions will be available as long as his father is willing and physically able to produce them.

Installation view of Danh Vo’s “Take My Breath Away” at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 9–May 9, 2018. Photo: David Heald. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2018.

Born in 1975, Vo spent only four years in his native Vietnam before his family fled the chaos created by the US military’s departure and a subsequent war between Cambodia and China. They eventually resettled as refugees in Denmark, where Vo would come of age.

After entering the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in 1998, he attended Frankfurt’s more conceptually driven Städelschule. Still, it took time for Vo to unlock his creative voice. “Good Life,” his first major solo gallery exhibition, opened at Isabella Bortolozzi in Berlin in 2007, the year the artist turned 32.

But judging by the number of solo exhibitions, few artists have been as in demand as Vo since that time, especially institutionally. The Guggenheim survey is his 26th solo show with an arts nonprofit in the past 12 years—and his 30th if you include installations of individual We the People sculptures.

How do we square this wave of activity with Levin’s statement that Vo “isn’t nearly as prolific as” some of his peers, then?

First, Vo tends to favor (extremely) minimal installations. Second, what fills his exhibition spaces often deliberately neutralizes the average viewer’s expectations. Roberta Smith described her initial reaction to “Take My Breath Away” by writing, “Not much looks like art, even by today’s standards. At times the museum feels almost empty, like the tail end of some deeply eccentric yard sale.” (The introduction pivots into a positive review.)

Beyond these tendencies, Vo also knowingly complicates the question of authorship in “his” exhibitions. “Almost all of his works possess some form of collaboration between his work and other people’s ideas or practices,” Albu explained. Even in his most collectible work, “the gold applied on his boxes is done by craftsmen in Thailand.”

Fittingly, the Brussels-based gallerist Xavier Hufkens, who started working with the artist in 2013, says he first encountered Vo’s work through the lens of another artist. In 2010, Vo was invited to re-install a retrospective of Felix Gonzalez-Torres at the WIELS in Brussels. “I was captivated by Vo’s understanding of Gonzalez-Torres’ work, his sensitive approach to the scenography and carefully created juxtapositions or dialogues,” Hufkens said.

Along with Hufkens, Vo now works with five other dealers worldwide, although only Marian Goodman represents him in multiple regions. (She declined to comment for this story.)

Danh Vo’s 2.2.1861 (2009–). Photo: Kristopher McKay ©Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundatino, NY. © Danh Vo.

How does the average buyer process Vo’s many exhibitions as hybrid curator-artist? How do you value an artist who has shown the capacity to make conceptually charged yet beautiful collectible objects while simultaneously operating most often as a harvester of sociocultural readymades?

Based on what we know, the answer may be that “the average collector” need not apply. Outside his two friendliest bodies of work, the pieces take on either a scale or a conceptual bent that removes them from the mainstream of private buyers.

So even as Vo continues to mount a slew of prestigious institutional and gallery shows, he remains somewhat of a limited proposition to buyers not inclined to prioritize concept over visual appeal and livability. This leaves more work for institutions and connoisseurs. And in a sense, this self-selectivity among true believers may be the greatest compliment Vo can receive as an artist—and the greatest endorsement for his long-term importance.