As usual, David Zwirner’s stand at Art Basel was swarmed during the fair’s VIP vernissage on Tuesday, with collectors and other market players jostling each other to get better views of the blue-chip works on offer—including a $20 million Gerhard Richter painting that sold within the first few hours. What was less usual, however, was that at the same time the scrum was playing out in the booth, a similar—though arguably more interesting—frenzy was taking place in the parallel dimension of the internet, where for the first time the gallery had inaugurated an online “booth” to coincide with the fair.

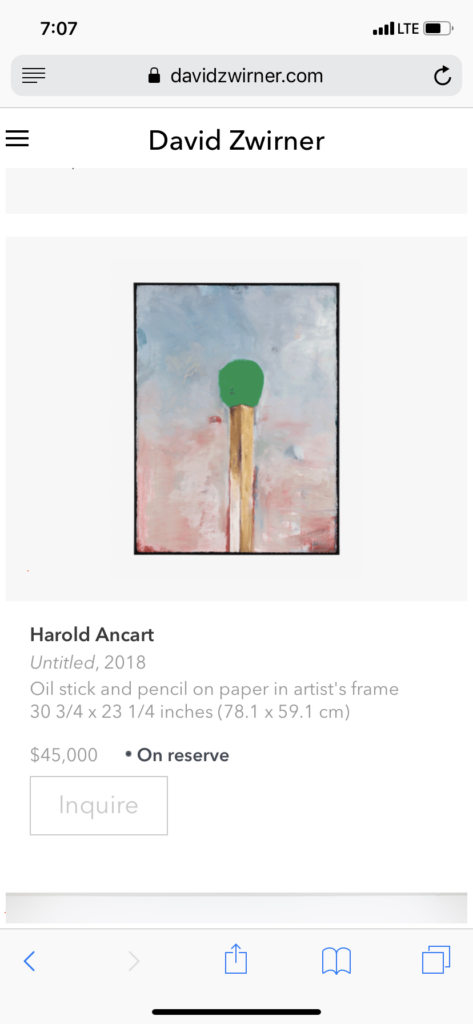

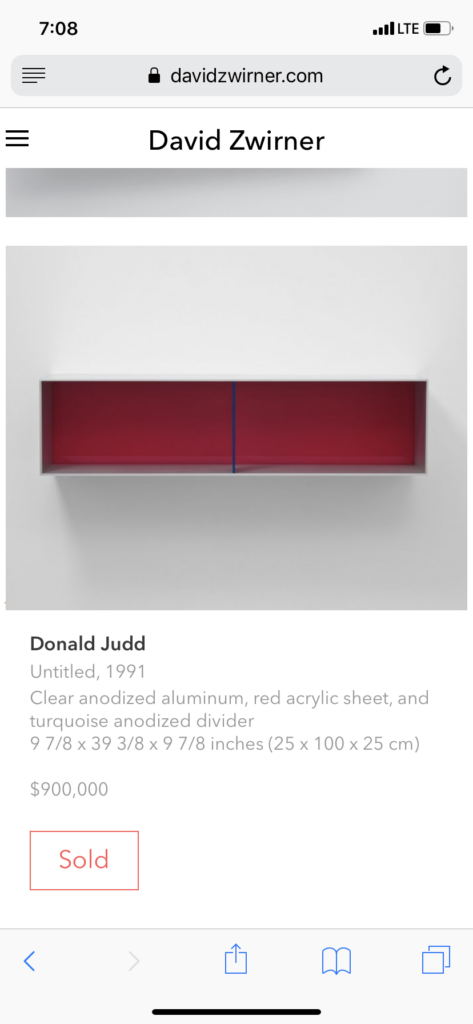

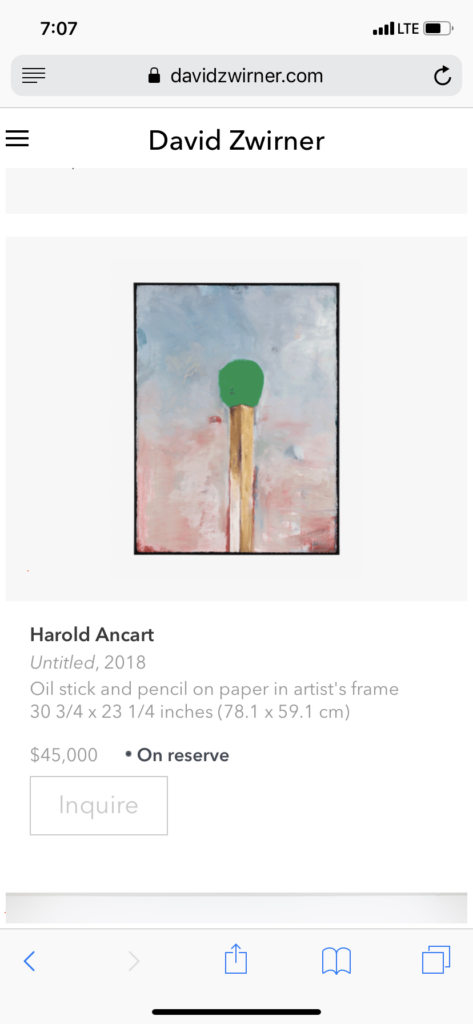

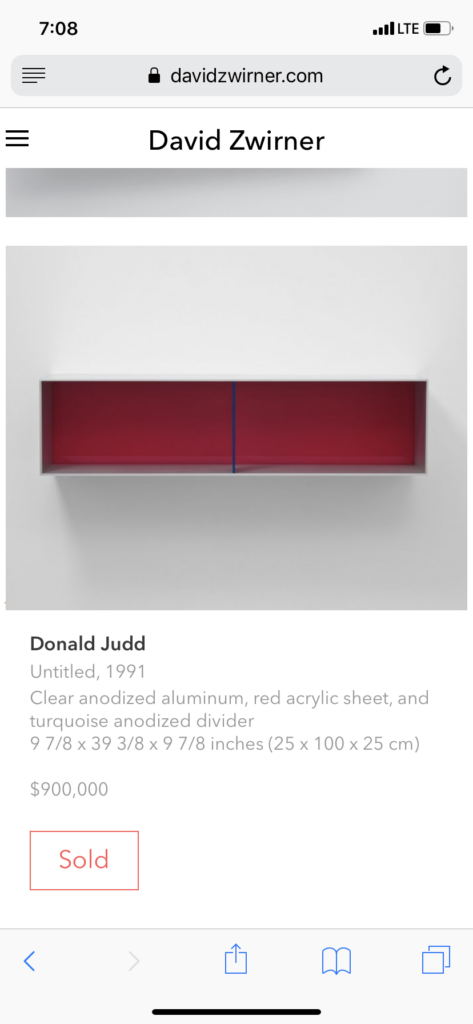

Called “Basel Online” and hosted on Zwirner’s own website, the virtual presentation was an effort of the gallery’s online sales director Elena Soboleva, based on the theory that a curated selection of first-rate pieces would find an eager web audience, scattered around the world (and not at the fair) and willing to pay top dollar sight-unseen. It worked. On opening day, a $1.8 million stainless-steel Yayoi Kusama pumpkin sold to a Russian buyer abroad. Someone in San Francisco jumped on a cherry-red Donald Judd box from 1991 for $900,000. A collector in Houston purchased a $200,000 Carol Bove sculpture. Meanwhile, a dreamy painting of a matchstick by art-market darling Harold Ancart went to Tokyo, where the online-retail billionaire Yusaku Maezawa—famous in art circles for buying a record-breaking Basquiat painting for $110 million in 2017—snapped it up for $45,000, all without having to fly to drizzly Switzerland.

The Kusama pumpkin. Screengrab from the Zwirner website.

All told, by dinnertime on Tuesday evening, eight of the 20 works offered digitally had sold to bring in $3.3 million, with five additional works totaling $1 million labeled as “on reserve.” (The total value of the works in the selection, the prices of which are listed on the website, is $5.6 million.)

Soboleva, who roamed the physical booth with an extra-large iPad to monitor the virtual action, was grinning from ear to ear. Having worked in the online sales arena before joining Zwirner last summer, she knew all too well the challenges that art e-commerce has faced to date. Now, at the gallery, she may have, to some extent at least, cracked the code. Traditionally, buyers are wary of making high-dollar art purchases—above $50,000, say—online without seeing the work in person. Here, the Zwirner gallery name, the famous reputations of the artists on offer, and the truly representative nature of the works (none of which was an oddball or unusual example) likely did much to carry collectors across that price threshold.

The painting Yusaku Maezawa bought. Screengrab from the Zwirner website.

The selling process remains a “hybrid model,” however, Soboleva explained: after providing an email to access “Basel Online” (therefore valuably growing the gallery’s mailing list), a potential collector could view the works in a rich but uncluttered multimedia display and then click an “inquire” link to be connected to a gallery sales director, who thenceforth would screen the buyer “just like if they were to walk into our booth at the fair.” In other words, Zwirner benefits from its existing strengths in customer service, while preserving the vetting process so important to its artists.

Meanwhile, the gallery has approached the virtual booth with the same care as if it were a physical one, working closely with artists and estates to get their best work, with Ancart and Jordan Wolfson providing pieces straight from the studio. “The key to the idea is that we bring works of very high caliber,” Soboleva said. “It’s all about getting the right inventory.”

The Judd sculpture. Screengrab from the Zwirner website.

While Soboleva has used the online viewing room—which founder David Zwirner has begun referring to as his “sixth gallery space” since it first launched in 2017, and which he has staffed and resourced accordingly—to do shows of lower-priced works before (like one of Josh Smith’s monotypes that sold out), the “Basel Online” effort represents a new level of seriousness in the gallery’s virtual approach. Its success, however, chimes with the gallery’s e-commerce findings so far: that over 50 percent of online transactions go to new clients, and that the 10 highest-priced sales before Basel had gone to collectors in cities where Zwirner doesn’t have an outpost. “For new collectors, it’s an opportunity to educate themselves,” according to Soboleva. “We try to represent a cohesive picture of the program.”

Soboleva said “we don’t have firm plans yet” about whether an online complement will become standard fair procedure for Zwirner from now on, but “given the success of this, we’ll definitely want to explore further.” What’s certain is that this new sales model isn’t going away, with a program of virtual “gallery” shows—one featuring work by Oscar Murillo, one by the photographer Stan Douglas, and then one of Franz West’s furniture—coming down the pike.