Art Fairs

What Can We Learn About Art Fairs From Liste, Basel’s Platform for Emerging Talent? Here Are Four Lessons

Liste, the world's premier fair for emerging contemporary art, can teach fair organizers and exhibitors a few things.

Liste, the world's premier fair for emerging contemporary art, can teach fair organizers and exhibitors a few things.

Tim Schneider

Despite continued agony over the subject, it doesn’t require a particle accelerator and a PhD in chaos theory to deconstruct the recipe for a healthy emerging-art trade fair. Just combine thoughtful young galleries, compelling little-known artists, and an open-minded public in an environment that allows for genuine conversations. Then make sure everything is priced reasonably from both sides—meaning, both the artworks on offer to the buyers and the spaces on offer to the exhibitors—and a small economy evolves as if by magic.

Sounds simple, right?

Sure. But a universe seems to separate an on-paper understanding of these elements and the skills to actually manifest them in the world. What makes the Liste fair Europe’s—and arguably the world’s—premier event for discovering new contemporary art is its ability to achieve this feat. Now in its 24th edition, the fair opened to VIPs on Monday morning, showcasing 77 galleries from 33 countries. And based on conversations with a cross-section of exhibitors from around the globe, it has lived up to its reputation once again while making enough tweaks to remain fresh.

Here are four lessons about fair presentation that we can learn from Liste’s continued success.

LISTE in Basel. Courtesy LISTE – Art Fair Basel. Photographer: Daniel Spehr.

Anyone who has never attended Liste would be hard-pressed to envision the level and variety of challenges posed by its building. In contrast to the numbing cubicle-farm setup that defines most fairs, experiencing Liste’s five levels often feels like the art-world equivalent of exploring a once-vacant castle commandeered by an international coalition of art rebels. (Go ahead, Google Street View it.)

In a conversation with artnet News on Thursday morning, the fair’s new director (and former gallerist) Joanna Kamm said that one of her first orders of business after winning the job last fall was to do a full walkthrough of the building with Fabian Nichele, Liste’s head of construction. Her original instinct was that she “would really love to open this up, to have more daylight and fewer walls.”

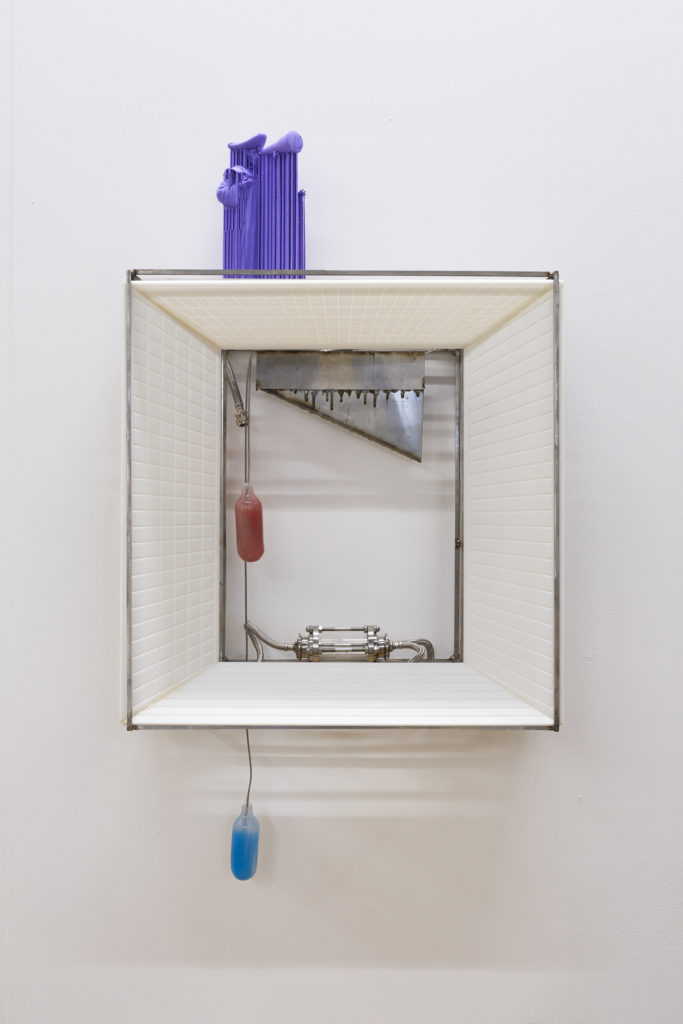

Installation view of Isaac Lythgoe’s works by Super Dakota, at Liste 2019. Photo:Isaac Lythgoe. Courtesy of Super Dakota, Brussels.

But just as important was to find ways to spatially highlight the art. As a result, many rooms are now organized around “a central point or theater” from which visitors can see each gallery’s full presentation.

Fairs normally subcontract this process to architects—a tendency that Jason Hwang, co-founder of Paris’s High Art, says “makes no sense” if you stop and consider it. “Architects don’t think about space the same way gallerists do,” he said.

The shifts sound minor on paper. (Returning gallerists gushed, for example, about wider hallways leading back to their stands.) But the cumulative effect seems to have been greater than the sum of its tweaks. Paul Soto, founder of Los Angeles and Brussels’s Paul Soto / Park View, described the environment as feeling more “art-fair proper” than the looser, scruffier “festival” vibe of his first Liste showing last year.

Hun Kyu Kim, Hunter’s Choice, 2019. Courtesy of High Art, Paris.

Despite the focus on Kamm’s ascension to the director’s chair, both she and the participating galleries highlighted the importance of Liste co-founder Peter Bläuer’s continued presence. Although he retired as director this spring, he remains vice president of Liste’s board and, according to Kamm, a willing but never imposing resource. “He never asked, ‘What are you doing?’” she said. But “every time I called him and asked how things were done before or told him about my ideas… he was always supportive.”

His support extended through opening night, when Bläuer and Kamm teamed up to take collectors on joint walkthroughs of the fair. One of them, Marian Ivan of Bucharest’s Ivan Gallery, noted the power of seeing the co-founding director and his successor working together in such genuine mutual regard.

Another type of continuity was important to returning gallerists. High Art chose to bring its stand full circle by contextualizing work by rising art star Max Hooper-Schneider, which the gallery presented during its first year at Liste, alongside that of Hun Kyu Kim, a young painter the gallery recently began working with whose works depict delirious scenes of cartoonish violence and discord between anthropomorphized animals.

“If you want people to care and follow you in the long term, the only way we’ve found to do it is to create a narrative that carries over the years,” said Hwang, who sought to draw a parallel between Hooper-Schneider’s installations of decaying or polluted ecosystems and Kim’s imagined melees.

The strategy seems to have paid off. According to Hwang, Kim’s paintings, which were priced at €8,000 ($9,025) to €10,000 ($11,280), “had no market” before the fair opened on Monday morning. (“Not even one person said, ‘Thank you for the preview,’” in advance of the fair, he said.) By Wednesday afternoon, the gallery had to put together a waiting list for Kim’s works. High Art also placed multiple pieces by Hooper-Schneider in the €25,000 to €50,000 ($22,565 to $56,410) range.

Anca Benera & Arnold Estefan, Debrisphere, 2019. Photography by the artists. Courtesy of the artists and Ivan Gallery, Bucharest.

It’s nearly impossible to read about Liste without seeing a reference to its unique model. Ownership of the fair transitioned to a nonprofit foundation after Bläuer’s retirement, and under his 23 years of leadership, the fair implemented numerous policies solidifying its identity as something approaching a sacred site for emerging galleries and artists across continents.

Yet those policies tend to amount to enlightened nudges rather than seismic reinventions of the art fair format. To spur more solo presentations, the fair charges exhibitors CHF 1,000 ($1,007) less if they show only one artist—a strategy that Kamm says has proven time and again the best way to introduce new talent. The combination of modest financial savings and sound market logic motivated this year’s 77 galleries to feature 38 total solo presentations, equivalent to about half the fair.

Then there is Friends of Liste, a patronage fund into which collectors contribute every year, with 100 percent of the money being passed along to participating galleries. While intelligent and admirable, the program’s practical benefits are relatively modest. In 2018, the Friends of Liste lowered stand costs for 10 galleries by CHF 2,000 ($2,014) each. This year, 11 exhibitors received funding through the initiative.

However, part of what defines Liste is the way its subsidies are distributed. Ambitious projects, particularly by single artists, tend to be rewarded.

Take Paul Soto / Park View as an example. In its second year at Liste, the gallery is presenting Dylan Mira’s 밤시각 Night Vision (2019). Projected onto a hanging sheet of Plexiglas with a holographic coating, the jittery, nearly unedited video chronicles the artist’s “epistemological journey” through her ancestral home on Jeju Island, part of the Demilitarized Zone between North and South Korea. While watching, viewers breathe in an herbal infusion Mira concocted with the guidance of a Korean herbalist, listen to an ambient soundtrack of field recordings collected while she slept, and are soothed by mist generated from electronic equipment hidden in a series of buckets.

In short, this is not the type of work normally championed at a commercial art fair. Yet Soto is enjoying his second year as a recipient of a Friends of Liste contribution. Priced at $8,000 to $10,000, editions of the piece were still available on Wednesday afternoon.

Isaac Lythgoe, Defend, 2019. Photography by Isaac Lythgoe. Courtesy of Super Dakota, Brussels.

This lesson may be cold comfort to other fairs, as Liste benefits from decades of its own success, as well as the incredible magnetism of Art Basel and the city’s world-renowned museums. As Damîen Bertelle-Rogier, founder of Brussels’s Super Dakota, put it to artnet News, “In terms of conversations and meetings, Basel is the Mecca” for contemporary art today, and within that construct, “Liste is the place to be.”

Super Dakota is among the 21 galleries showing at Liste for the first time this year, and the gallery went the single-artist route. Their stand focuses on young artist Isaac Lythgoe, who synergizes traditional and cutting-edge sculptural techniques into thematically dense works addressing everything from timeless systems of power to the evolution of mythology. (Mount Olympus has given way to Disney and Hollywood, if you were wondering.) Lythgoe’s works attracted both institutional and commercial attention, with four sculptures selling in a range between €6,500 ($7,330) and €18,000 ($20,300) by Wednesday.

Marian Ivan of Ivan Gallery contrasted his experience here at Liste with Frieze New York, where the gallery has exhibited since 2013. While they have found success in the Frieze tent, they have a “very specific audience” there—one that is almost uniformly American and prone to make a decision on works “in the first hour” due to the high level of competition.

Liste offers something else. “It’s a context where we can come with projects that are less commercial,” Ivan says. “The audience is much more open to experiencing works at a deeper level.”

Installation view of Patrick Godddard’s works in the booth of Seventeen, London, at Liste 2019. Courtesy of Seventeen, London.

It’s not just about sales, either. David Hoyland, founder of London’s Seventeen, enjoyed both institutional and commercial success. The gallery focused its stand on Patrick Goddard, who Hoyland describes as a “punk” multimedia artist whose work focuses on class anxiety and how artists become “the broom that sweeps through the warehouse to be gentrified.”

The gallery placed Bin Juice (2019), an installation of 200 lead fish mostly scattered across the floor of Seventeen’s booth, with a “very good” German collection for £10,000 ($12,680). But a curator also offered Goddard a museum show in the opening days of the fair based partly on the strength of the booth.

Still, the most fitting symbol of Liste’s DNA may be Hoyland’s reaction to visitors’ interactions with Bin Juice. Clearly, the fish had been laid to make visitors perpetually anxious about kicking the artwork. Hoyland gleefully said that, by Wednesday, “there [were] no un-kicked fish.” But with so many works and so many people coming through, had anyone tried to simply pocket one?

“If none of them have been stolen by the end of the fair,” Hoyland said, “Patrick and I will be disappointed.”