The possible use of A.I. for authenticating artworks is a topic that has made headlines in recent years but has, so far, had next to no real-world applications within the art market. Last month saw the very earliest signs that this may be changing at the market’s periphery, with Germann Auction House in Zurich pioneering the use of A.I. authentication to back the sale of three artworks by Louise Bourgeois, Marianne von Werefkin, and Mimmo Paladino.

“This is a groundbreaking moment where A.I. has directly influenced a real market transaction, enabling the sale of a piece [by von Werefkin] that lacked a traditional authenticity certificate from an expert—something that, not long ago, would have rendered it ineligible for auction,” said Carina Popovici, founder of Art Recognition, the Swiss start-up providing the A.I. authentication service. She added that other auction houses have already expressed interest since the sale.

A.I.-powered authentication has certainly captured the art world’s attention, but this has not always been for the best reasons. When in 2021, Art Recognition declared that its A.I. algorithm had found Rubens’s Samson and Delilah at the National Gallery in London to be a fake with a probability of 91 percent. The news made a splash but, in the end, the bold assertion could not be backed up and was easy for the museum to dismiss.

In what was quickly dubbed the battle of the A.I.s last year, two different A.I. algorithms came to opposing conclusions about whether the same painting could be by Raphael. The incident showed that A.I. is by no means an objective measure and its accuracy is heavily affected by how it is made, including the quality, diversity, and detail of its dataset. The significant complications that come with building effective A.I. authentication tools are covered in greater detail in a new episode of The Art Angle podcast and my book A.I. and the Art Market (Lund Humphries), out in the U.S. on February 13, 2025.

With all the potential roadblocks, what is the case for A.I. authentication? While human expertise remains key to contextualizing an artwork to determine its likely attribution, A.I. has the upper hand when it comes to analyzing formal details on the picture plane and comparing these with other examples from the same group (the same artist, for example) or counterexamples (works by a different artist of the same style/period, perhaps).

Mimmo Palladino, Lo Spirito della Foresta (1981). Image courtesy of Germann Auctions.

Sometimes, A.I. spots patterns that humans can’t perceive, a skill known as “pattern recognition.” Its effectiveness partly relies on the computer’s vast memory, which allows it to “see” every inch of many images at the same time. By comparison, a human connoisseur studying one artwork at a time and entrusting what it sees to the infamously fallible human memory has obvious limitations.

The answer, therefore, is surely to combine A.I.’s strengths with our own, and other scientific methods like pigment-testing, to build a more robust approach to authentication. However, this very high-stakes process can have millions of dollars riding on its outcome so, as well as building reliable tools, proponents of A.I. authentication must win the trust of art-market players and gain credibility with insurers and legal experts.

Germann Auctions’s pilot run of the new technology doesn’t appear to have put off potential buyers. During its sale of works collected by Swiss curator and museum director Martin Kunz on November 23, an Art Recognition-certified, untitled ink drawing made by Bourgeois in 1945 sold for CHF 28,000 ($31,600), falling just short of its $34,800 low estimate. Additionally, Lo Spirito della Foresta a 1981 collage by Italian artist Mimmo Paladino sold for CHF 19,000 ($21,500), again short of its $23,200 low estimate.

The authenticity of both these works was already backed up by the artists’ respective archives. Paladino is also still alive, further alleviating any doubts about his authorship of the collage.

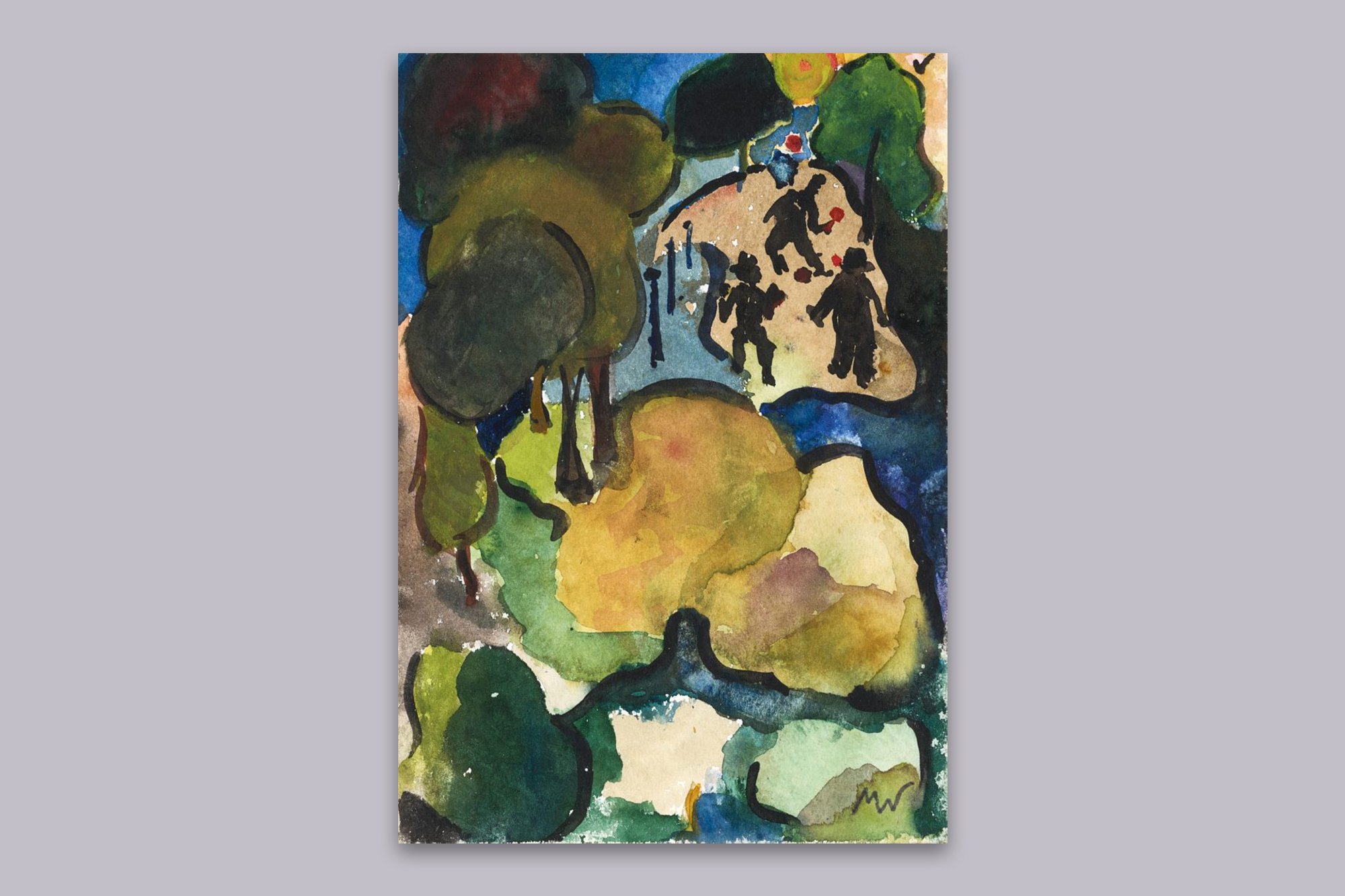

The untitled, undated watercolor by von Werefkin, a Russian artist associated with German Expressionism who has recently received institutional attention, was offered two days later on November 25. It fetched CHF 15,000 ($17,000) over a high estimate of $9,300.

This latter work, according to Popovici, “lacked any prior evidence of authenticity, such as expert certification. This made it a pivotal test case to gauge how the market would respond to the idea of selling an artwork authenticated solely by A.I. As we have seen, the outcome was a resounding success.”

Germann Auctions decided which three works would be backed by Art Recognition. Though the A.I. did not on this occasion offer a percentage indicating the likelihood of authenticity, Popovici said that this figure was high in all three cases.

“Authenticating art with A.I. is significantly more efficient and cost-effective compared to traditional methods, which require physically sending the artwork to an expert for inspection,” said Fabio Sidler, CEO of Germann Auctions. “Since A.I. only requires a photograph, there are no further costs associated with transportation and insurance.”

Since the days of its controversial judgment on Rubens’s Samson and Delilah, Art Recognition has made strides in improving its credibility. It has brought on board a scientific advisor, Eric Postma, professor of A.I. at Tilburg University in the Netherlands, with whom Popovici has co-authored two peer-reviewed papers outlining the company’s methods. Art Recognition offers its authentication services at a charge of around $2,200 per work, with the price subject to the level of detail offered about the A.I.’s judgment.