Artnet News Pro

‘He’s Like a Puppet-Master’: How Frank Bowling Is Directing the Production of His Art—and His Market—in His Twilight Years

Bowling's market is expected to reach new benchmarks as he debuts with mega-gallery Hauser & Wirth.

Bowling's market is expected to reach new benchmarks as he debuts with mega-gallery Hauser & Wirth.

Naomi Rea

Frank Bowling was tired.

The artist, considered among the greatest proponents of British abstraction, has been knighted by the Queen; elected to the Royal Academy; and the subject of an extraordinary retrospective at Tate Britain in 2019. At the age of 87, he has just opened a two-city exhibition with mega-gallery Hauser & Wirth, and the gallery says early sales at prices ranging into the multimillion dollars have been “exceptional,” with major paintings being sold into prominent international collections.

It wasn’t always this way. When I visited Bowling at his South London studio in 2020, I congratulated him on all the recognition. “It has been a long and arduous journey,” he said.

The making of Western art history is not a particularly organic or meritocratic process. And Bowling entered the London art scene in the 1960s with the deck stacked against him. His ascension was stymied in turn by racism, his oscillation between London and New York, and the art market’s disinterest in abstract painting.

The rise of Bowling’s star in his twilight years now reflects a mainstream art world that is slowly coming to terms with centuries of neglect toward non-white, non-male artists. Many of them did not live long enough to see their work recognized. But witnessing such a dramatic shift in fortunes can be wrenching in its own way.

“It was staggering for somebody, who has worked every day since 1958,” the artist’s son Ben Bowling told me when I visited the studio. “Sixty-two years of continuous labor, and for decades he was not selling anything, not being shown, not being respected. For it to all happen now is essentially quite traumatic.”

As the artist’s health declines, he is thinking hard about his legacy. He cut ties—and waged a bitter legal battle with—the gallery that helped steer his rise to fame, and joined forces with a mega-gallery that has expertise in the big business of artist estates.

This drama is a heightened version of one that affects many artists who gain renown late in life. Who do you trust when art market vultures begin to circle overhead? And what remains of one’s legacy once the bones are picked dry?

When I visited Bowling’s studio, nestled in a cobbled Victorian yard amid weavers, silversmiths, and woodcarvers, he had just returned from a two-month hospital stay.

Using a wheelchair and suffering from severe back pain and lack of sleep, he was desperate to get back to work. The canvas in progress was something he had begun painting in mind’s eye on the hospital ceiling. Bending down, I noticed the pic-line from his IV drip gelled onto it.

These days, physical limitations mean that Bowling directs his studio assistant—his grandson Frederik—using a laser pointer. He’s usually working on multiple canvases at once.

“I’m just trying to decipher what he says, and sometimes I get it right,” Frederik told me. “It’s a bit of a struggle and sometimes it’s kind of nerve-wracking… because you don’t actually know what you’re doing. He’s controlling just like a puppet master, really.”

A studio session can last anywhere between 90 minutes and three hours, and a 10-foot painting takes about a month to complete. During my visit, recent paintings glimmered in the afternoon light. His son and grandson said they had been joking about Bowling going a little heavy on the pearlescence. But their respect for the artist’s vision has always left him in control.

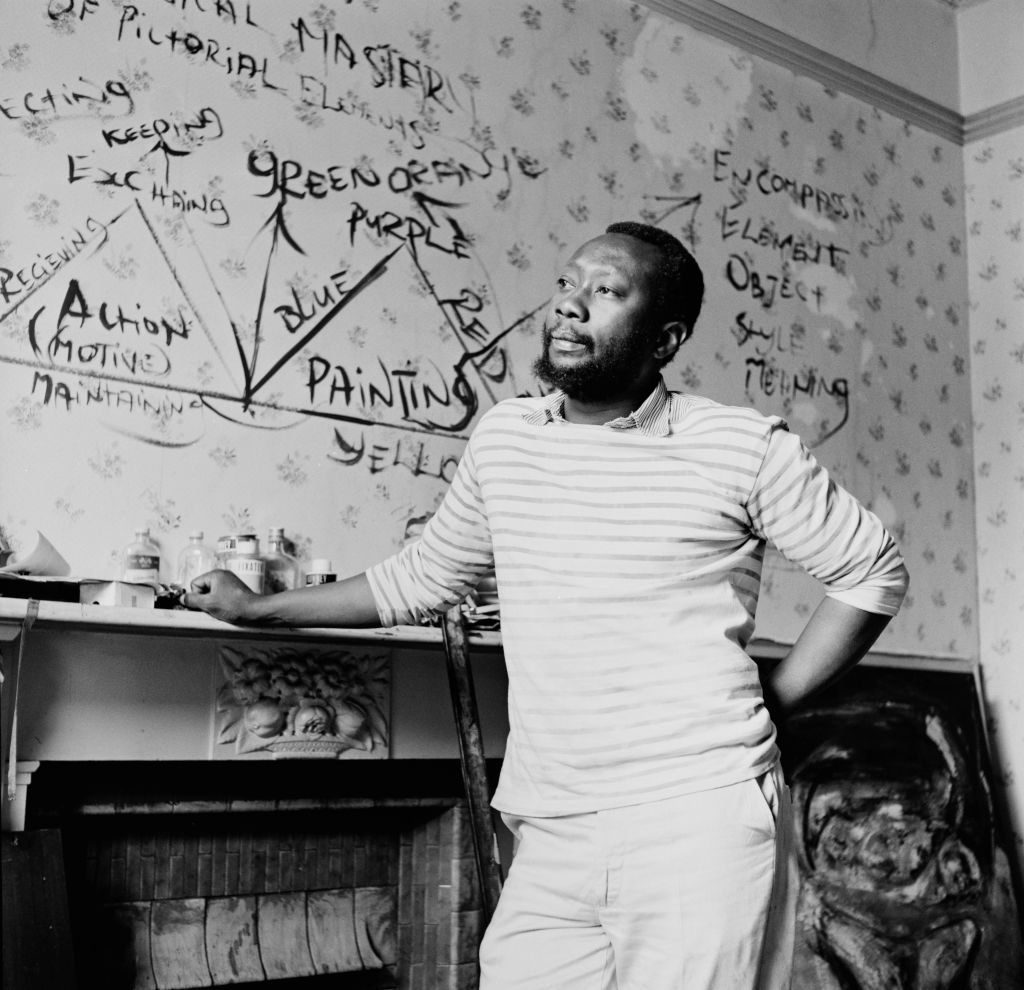

Frank Bowling in a studio, London, 1962. Photo by Tony Evans/Getty Images.

Frank Bowling was born in Bartica, Guyana, in 1934. He came to London during the Windrush Generation with aspirations to become a poet, but by his own account ended up getting “hooked on painting” and earned a scholarship to the prestigious Royal College of Art.

After he graduated in 1962, Bowling became an active part of the emerging London scene. But as his (white) peers like David Hockney, Derek Boshier, and R.B Kitaj began to attract considerable buzz, he struggled to find commercial gallery representation.

Bowling’s hard-to-categorize paintings of people and animals were out of fashion in an art world that was falling in love with Pop and Conceptual fare. And then there was the matter of race. Bowling recalled one emblematic incident in 1964, when the then-director of the Whitechapel Art Gallery told him openly: “England is not ready for a gifted artist of color.”

This came as a shock to an artist whose native Guyana was still at that time a British colony and who very much considered himself to be British. As time went on, Bowling consistently resisted attempts to pigeon-hole him as a Black artist. He reluctantly entered his work into the inaugural Festival of Negro Art in Dakar, Senegal, in 1966—and felt conflicted when he won. “He felt… he went from being considered a very young promising artist to just being looked at as a Black promising artist,” said Tate curator Elena Crippa, who organized the 2019 retrospective of Bowling’s work.

Frustrated with his reception in the U.K., Bowling left behind his first wife and three sons to move to New York. There, he fell in with a group of other Black artists, including Al Loving and Jack Whitten, who were staking a claim for abstraction at a time when white male artists were dominating the conversation.

It was in New York that he began to produce—and gain near-immediate recognition for—his “Map” paintings, which present fields of color stenciled over with different continents. The series was the subject of a solo exhibition at the Whitney in 1971.

Over the next few decades, Bowling secured sporadic recognition—barely enough to keep him engaged with the art world when many others might have been driven to quit. (London’s Serpentine organized a solo show of his work in 1986; Tate acquired a painting the following year, its first-ever acquisition by a living Black British artist.)

Commercial success was even harder to come by. “During the 1980s, there was this idea that painting was dead and there seemed to be little interest in abstraction among collectors and not everyone really understood what Frank was doing,” the artist’s son Ben Bowling told me. In fact, the artist had no commercial representation in England at all until the early 2000s, surviving on piecemeal sales from international dealers.

The neglect he suffered did not stop him from returning to the studio day after day. When I met him there, he joked about how people from the Southern hemisphere have a “bug about working” and explained that, like his mother who earned the nickname Chrissie after she was born on Christmas, he doesn’t do weekends or holidays off.

Instead, Bowling pushed himself toward constant reinvention. The maps and the poured paintings of the 1970s gave way to a new, more tactile body of work that incorporated gels and the detritus of his own life.

“In some ways, not having the recognition for my work that I did in the 1980s and 1990s did me a favor,” Bowling said. “Instead of having to deal with the froth, I was just able to get on with making the very best work that I could.”

The turn of the century brought the first major sea change in Bowling’s stature. In 2003, a group of his map paintings were shown during the Venice Biennale, and he had his first commercial gallery show in England since the 1970s.

The artist benefitted from a wave of rising curators more interested in excavating neglected art histories than talent-scouting the next big thing. “It was the beginning of that moment where, particularly for the Venice Biennale, it was about going back and recovering,” Tate curator Crippa told me.

Then, in 2005, he was elected to the Royal Academy, an institution that had been snubbing him since his early masterpiece, Mirror, was the talk of its 1966 Summer Exhibition but failed to sell. Six years after that, art historian Mel Gooding published the first comprehensive monograph of Bowling’s work, and a group of his poured paintings were shown at Tate in 2012.

“The institution had no interest in Frank Bowling prior to that moment,” Courtney J. Martin, the curator who organized the display, said. While she had initially proposed a full-scale exhibition of Bowling’s work, the idea received pushback from the marketing department, which did not feel that the exhibition would sell enough tickets.

Meanwhile, Bowling’s long-stagnant market was beginning to stir. He had benefitted from sustained support from a number of Black dealers, including Terry Dintenfass, Peg Alston, George N’Namdi, and Rush Arts Gallery. But he did not find a permanent home until he settled with Hales Gallery in 2011. The stable commercial support marked a major shift for an artist who had once worried about being able to afford to buy his paint.

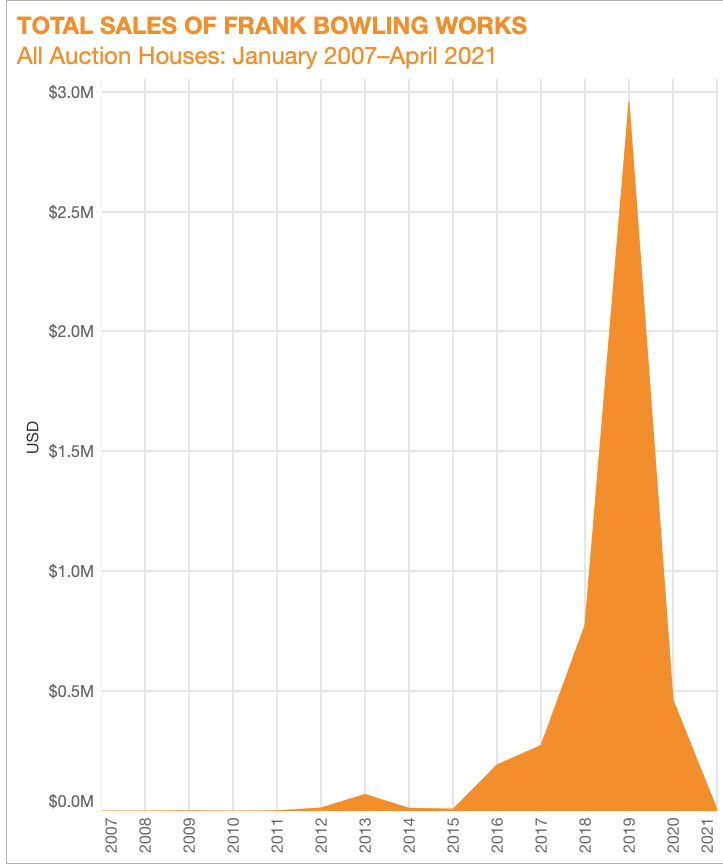

© Artnet Analytics

Then, what has become a dynamic familiar to many late-in-life artistic achievers began to unfold. Institutional recognition led to measured commercial success, which propelled even greater institutional recognition. That, in turn, fueled even more frenzied commercial success. And just like that, most institutions and all but top collectors were priced out.

As Hales toured his work to international art fairs and held exhibitions deep diving into particular series, private collectors like the American philanthropist Pamela Joyner began to take notice.

The tide shifted more dramatically in 2017, with the opening of a major exhibition organized by the late curator Okwui Enwezor at Haus der Kunst in Munich and Tate Modern’s “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963–1983.”

Between then and now, Bowling’s work came to auction 46 times. Paintings from the 1960s and ’70s swiftly began achieving six-figure sums. Bowling’s current auction record stands at £695,000 ($872,000), achieved at Christie’s around the time of his 2019 Tate retrospective. According to Angus Granlund, Christie’s head of Modern British art evening sale, 10 clients from four different continents duked it out for the 1963 work, Beggar No. 3, evincing its “truly global appeal.”

At the time, dealer Paul Hedge told Artnet News that the artist’s smaller canvases were priced around $250,000 to $500,000 on the primary market, while large canvases were selling for upwards of $1.5 million. Bowling had also secured formal representation in the U.S., showing with Alexander Gray Associates for two years. (Gray declined to comment for this story.)

The loans for the long-awaited Tate show, Crippa said, largely came from private collections—reflecting the growth of Bowling’s market over the preceding five years and exposing the “shocking reality” of just how poorly his work was poorly represented in U.K. museums.

In the decades leading up to the Tate show, Bowling had bonded with his adult sons, who speak fondly about discovering their father’s love of verbal jousting and good whiskey. He also reconnected with and eventually married an old friend from art school, fellow artist Rachel Scott, whom he involved in the production of his work as well as the management of his business affairs.

In 2001, his eldest son Dan died suddenly at age 39. Beset by that unexpected tragedy and against the backdrop of his own growing profile, Bowling began to think seriously about estate planning. He involved his family in the conversation early.

“We had all heard horror stories about artists passing away and leaving their family to sort out a terrible mess, and we realized that could be avoided with a certain amount of careful thought,” Ben Bowling told me.

In 2018, Hales Gallery introduced the family to the Institute for Artists Estates (IAE) in Berlin, and Bowling sent his two surviving sons to take a crash course in estate management.

“There, our eyes were opened to the amount of work involved in managing the relationships with museum curators, collectors, academics, in addition to the work with commercial galleries,” his son Ben said. “We learned about art law, financial management, archiving, and the importance of a catalogue raisonné. It was wonderful to be part of a group of artists’ relatives all of whom were facing a similar situation to ourselves.”

A report commissioned from the IAE became the blueprint for Bowling’s family to create a fully functioning studio team, including studio managers, assistants, researchers, and an archivist.

Loretta Würtenberger, who founded the IAE after inheriting the estate of a Bauhaus artist, said it is rare for artists to be so proactive. “The best way to avoid dispute is if an artist leaves clear instructions,” she said. “To be able to do that, he must stand up to dealing with his own death, and you must be quite brave to do that.”

As their understanding of the machinery of estate management grew, Bowling and his family became aware of the inevitable role the market has to play in any conversation about legacy. Careful placements in prominent collections provide new avenues for visibility; careless ones can do harm.

“There’s no point talking about maintaining your place in art history if the work just disappears,” Ben Bowling said, adding that his father had lamented not being taught about the market in art school. “Frank has said on numerous occasions… ‘These paintings are like my children and I want them to be out in the world,’ which is great. But out in the world does not mean in some storage vault in the world of some speculator, who is going to flip it in a couple of years.”

As he faced the reality that his studio would one day become an estate, Bowling began to consider what his family, and his legacy, would need from a gallery. His rising fortunes were giving him access to more powerful dealerships, like Pace and Hauser & Wirth, than he’d ever had access to before.

After taking advice from various sources including art historians, writers, and market players, Bowling decided to terminate his relationship with Hales Gallery, citing an alleged breakdown in trust. As one might imagine, breaking up with a business that had invested time and energy into growing his profile did not go smoothly.

A statement from Bowling’s legal representation seen by Artnet News at the time cites “serious breaches” of their agreement, including the gallery’s failure to account for art-sale proceeds and the location of specific works.

In February 2020, Bowling filed a £30 million lawsuit against Hales in London’s High Court, accusing the gallery of withholding from him 110 artworks (valued at £14 million) and £1.8 million in cash. The suit demanded the gallery provide “a proper account of all its dealings and transactions relating to the sale of his artwork.”

The East London gallery fired back, counter-suing for up to £14 million in lost commission and damages for terminating their deal, and accusing Frank’s sons in court papers of poisoning the gallery’s relationship with Bowling and trying to wrest control of the artist’s legacy from his wife, according to the Evening Standard.

As of this writing, the dispute has been resolved behind closed doors, and both the studio and the gallery are keeping quiet about the details. In a joint statement given to Artnet News, both parties adopted a far more chipper tone than they had during the dispute, noting that are “pleased” to have found a “mutually agreeable” resolution.

They declined to specify whether a financial settlement has been made or clarify the status of the more than 100 paintings cited in the lawsuit. (Notably, works by the artist are still listed as “available” on Hales Gallery’s website.)

“Hales had the pleasure of working with Sir Frank for many years, successfully bringing his work to the attention of both private collectors and public institutions through various projects and exhibitions,” a spokesperson for Hales Gallery said. “The importance of Bowling’s artistic legacy is undeniable, but sadly it has not always been recognized as such. We are delighted to have played a part in the process of bringing this groundbreaking career to a broader light and are thrilled to see this process furthered even more today by our colleagues across the industry.”

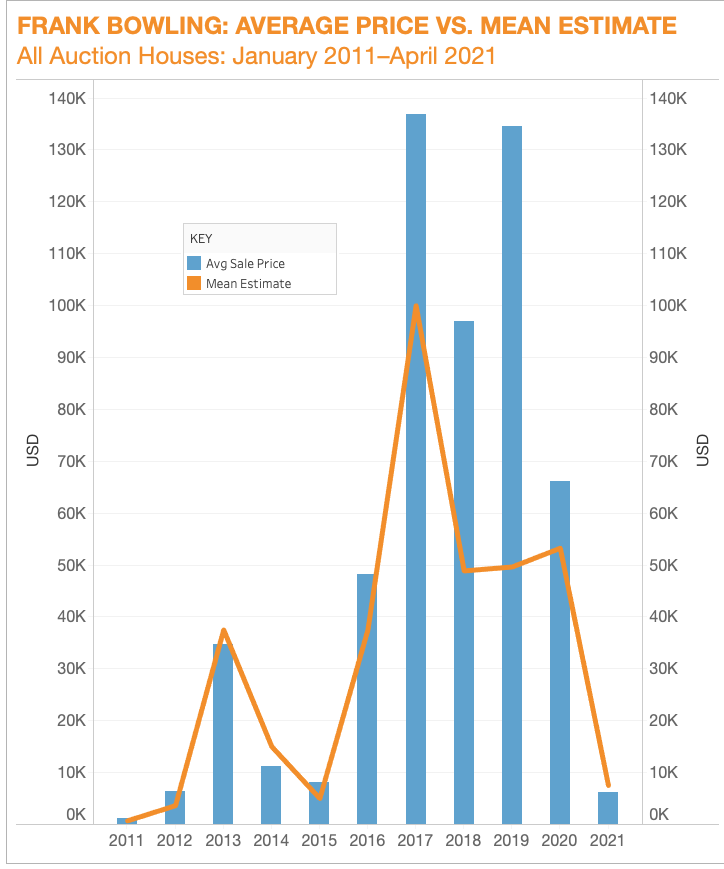

© Artnet Analytics

Eight months after filing suit against Hales, Bowling announced that he had joined Hauser & Wirth. He was swayed in part by the mega-gallery’s experience managing nearly 40 other artist estates—not to mention its extensive resources and willingness to involve him in preparations for the future.

Neil Wenman, Hauser & Wirth’s senior director, credited Hales with laying the groundwork for Bowling’s stardom. “I think they were absolutely central to [his rise to recognition] and in many ways they did a great job.” Wenman said.

What Bowling described as a “breakdown in trust” with Hales raises important questions about the role the simple matter of trust plays in the big business of artist estates. A breach of trust resulted in a gallery that had recognized his worth (relatively) early losing out on the fruits of that labor. Meanwhile, a gallery that swooped in as his market was flourishing will likely end up profiting from it long after the artist is able to.

Now embarking on a new chapter of his career, Bowling has unveiled a career-spanning exhibition on view across Hauser & Wirth’s New York and London locations, which includes major loans as well as works for sale.

The gallery plans to continue the strategy set out by Hales, focusing on museum exhibitions and new scholarship, albeit with a more global platform. The five-year vision includes a major exhibition of new work at the Arnolfini in Bristol this summer and other exhibitions in the U.S., Europe, and Asia. The gallery will be focus on teasing out areas of the practice that have been overlooked, such as his writing and later work.

Christie’s Granlund confirmed that the scarcity of Bowling’s work from the 1960s always keeps it in high demand, while the vibrance and texture of his 1970s poured paintings consistently resonate with buyers. But tastes may already be evolving: three paintings executed in the past 15 years figure into his top 10 prices at auction.

Installation view, “Frank Bowling – London / New York,” Hauser & Wirth New York, 22nd Street, 2021. ©Frank Bowling. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo by Thomas Barratt.

Considering Bowling’s age, Wenman said that organizing exhibitions quickly is a priority. It is a lesson he learned from working with one of Bowling’s peers, Jack Whitten, who joined the gallery in 2016 and died before he was able to see several major exhibitions come to fruition.

“It’s important for us … to try to make as many moments as possible occur for [Bowling] so he too can appreciate them and, and see that recognition and that adoration of his work himself,” Wenman said.

When it comes to sales, the gallery is doing its best to avoid speculators by controlling placement, introducing right of first refusal agreements where necessary, and prioritizing institutions. Prices for the works still begin at around $250,000 for the smaller canvases but now go into the multimillion-dollar range for large works.

Hauser is also playing a long game. They are encouraging the family to build a core collection of top-quality works from across Bowling’s career and working to ascertain the whereabouts of those that are missing. To keep the auction market under control, they are considering purchasing back works headed to the block and asking Bowling to hold back others from sale entirely, including the series he is working on now.

“It may well be that in years to come, we will look back and say that the last 10 years of his work is his most important,” Wenman said.

Part of the challenge of controlling supply is that, contrary to popular belief, there isn’t that much work left. “Even during the ‘90s, when his commercial representation wasn’t at its greatest, works were still being sold and placed,” Wenman said. “And there aren’t even that many kept by the family.”

Outside of the regular strategy session with his family and the gallery, however, Bowling is keeping his eye on the canvas. “I paint as I’ve always painted,” he said. “That’s what career is about for me—making paintings.”

His family, meanwhile, are beginning to feel the weight of a legacy on their backs. Today, Bowling’s work is in more than 50 institutions worldwide, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Royal Academy. “The opportunities that are appearing at the current moment are extraordinary and almost overwhelming,” Ben Bowling said. “It is incredibly exciting in terms of options, but we have still got a huge amount of work to do to bring our dad’s work to the attention of the general public.”

Installation view, “Frank Bowling – London / New York,” Hauser & Wirth New York, 22nd Street, 2021. ©Frank Bowling. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo by Thomas Barratt.

Frank Bowling’s extraordinary career illustrates how the market and the museum contribute to shape an artist’s legacy—one rarely evolves in isolation. And evolution is the only constant.

“Art history is alive, it is always growing, always changing,” curator Courtney J. Martin told me. “When I was trained as an art historian, the idea that you fixed living people was not done. And so I think that… what we will one day think about Frank versus what we think about him right now could be radically different.”

While Bowling is laying the groundwork for the reception of his work in the future, he recognizes that there will come a point when he must relinquish control.

“What people say when I’m not in the room doesn’t concern me,” Bowling told me. “I’d rather that people ask me directly, but I’m quite happy when I hear my wife or my sons talking about my work because I am seeing my work through the eyes of my family. Sometimes they see things that I don’t see. And then I tell them, ‘You are ahead of me here…'”

“Frank Bowling—London/New York” is on view at Hauser & Wirth, New York, 542 West 22nd Street, May 5–July 30, 2021, and Hauser & Wirth London, 23 Savile Row, May 21–July 31, 2021.