Art & Exhibitions

Freaks and Geeks Dominate Matthew Marks Survey of Alternative Artists Since the 1960s

A worldly, if jarring and unruly, show.

Courtesy of Matthew Marks.

A worldly, if jarring and unruly, show.

Christian Viveros-Fauné

Jim Nutt, I’m Wet (1969) and Karl Wirsum, Chairy Blossom (1969).

Courtesy of Matthew Marks.

Visit Chelsea’s Matthew Marks’s galleries on 22nd Street during the next few weeks, and you’ll encounter contemporary art’s version of the Island of the Misfit Toys. On view simultaneously at Marks’s three spaces, the exhibition titled “What Nerve!” highlights the work of several groups of artists the gallery claims constitute “an alternative history of American art since the 1960s.” In the lingo of televised X-Mas specials and Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, this tripartite show celebrates birds that swim, boats that can’t stay afloat, and trains with square wheels.

Organized by independent curator Dan Nadel, “What Nerve!” reprises a larger version of a show seen last fall at the RISD Museum in Providence. Though the loosely installed RISD exhibition featured additional artists (among them Christina Ramberg and William N. Copley), Matthew Marks’s more pristine display underscores the same canon-busting argument: a geographically scattered, raunchy counter-narrative exists as a foil for New York’s less-is-more postmodernism. Exhibits one through four include raucous works made by several crucial coteries of “regional” creators. These are, in chronological order, the following outsiderish groups: Chicago’s Hairy Who (active from 1966 to 1969), California’s Funk artists (active around 1967), Ann Arbor’s Destroy All Monsters (active from 1973 to 1977), and Providence’s Forcefield (active from 1996 to 2003).

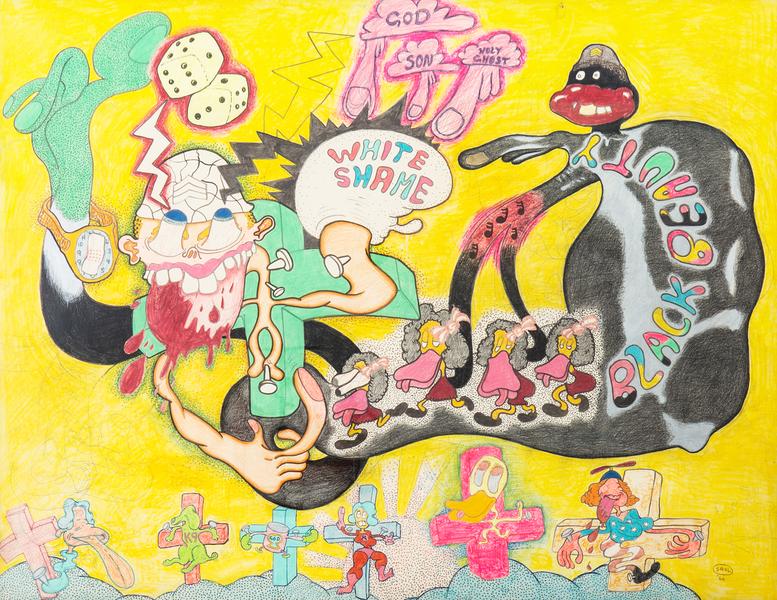

Peter Saul, Black Beauty White Shame (1966).

Courtesy of Matthew Marks.

If you’re an artist, the go-along story goes: it pays to live in New York City. Among the alternatives to the Gotham-centric plan is the currently impoverished notion that staying local can help draft alternatives to the mainstream. Unlike music’s more diffuse influences (Seattle Grunge and Philadelphia Soul are but two of many local musical genres to go national and, eventually, global), visual art’s regionalist arguments have lost ground since the anti-modernist days of Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood. That’s just one reason “What Nerve!” makes such a weird impression. There’s the shock of having missed aesthetic affinities hiding in plain sight, and also the realization that alienation is still the Krazy Glue joining many artists and rockers together. As Nadel writes in the show’s press release: “When confronted with a system that seems impenetrable, outsiders tend to band together.”

An unruly set of neatly arrayed paintings, sculptures, drawings, posters, film, books, fanzines and other ephemera, “What Nerve!” kicks off with an ear-splitting bang: Forcefield’s 11-minute visual and auditory earthquake Tunnel Vision. A film extravaganza that begins with the group’s members (Mat Brinkman, Jim Drain, Leif Goldberg, Ara Peterson) dressed as torch-bearing medieval creatures inside a sewer setting fire to an organ, the projection advances through swirling abstract patterns and a high-decibel score to reach a sensory-pummeling crescendo. Dark and nonsensical, the film is predicated on being as subtle as a jackhammer. Similarly, Forcefield’s eye-catching “shrouds” (knitted garments the group wore in films and performances) and “dudes” (life-size mannequins in psychedelic get-ups) depend heavily on noise-band discord for their loud, color-clashing aesthetic. (Unsurprisingly, these sculptures were standout objects at the 2002 Whitney Biennial, the short-lived collective’s last outing before this show.)

Robert Hudson, Inner-Mission (1965). Courtesy of Matthew Marks.

Another group to adopt the kick-out-the-jams ethos of non-NYC musicians—think The MC5 and The Stooges—were native Michiganders Destroy All Monsters (Mike Kelley, Carey Loren, Jim Shaw, and the mononymous Niagara). Though they never exhibited as a collective, the members formed a band and collaborated intensely on the group’s records and zines. Several Cary Loren photographs in the exhibition feature the late Kelley and Shaw in B-movie getups—both figures eventually crossed over into the art mainstream. Another work that embraces kitsch vernacular is Shaw’s The End Is Here. A mimeographed booklet the wolfish artist modeled after scavenged bible thumper tracts, this piece of copycat proselytism shares a title with the artist’s upcoming October solo show at the New Museum.

Funk, curator Nadel tells us, is the one group included in “What Nerve!” whose origins were not self-selecting. It sprung, instead, from the title of a 1967 exhibition assembled by curator Peter Selz. According to Selz’s alt-history, Funk’s members (Jeremy Anderson, Robert Arneson, Joan Brown, Peter Saul, Roy De Forest, Robert Hudson, Ken Price and Peter Voulkos) provided a “hot” Bay Area reaction to the reigning “cool” of Los Angeles finish fetish. But whether Selz identified a full-fledged movement or a passing trend, Funk artists excelled at the opposite of Light and Space purity. At Matthew Marks, Peter Saul’s incendiary drawing Black Beauty White Shame gives a master class in non-conformity. Made in 1966, this piece of Boschian iconoclasm appears ever ready to take on all comers—minimalism, corporate America, voting-rights opponents, and just about every other champion of the status quo.

Ken Price, Red Egg (1968).

Courtesy of Matthew Marks.

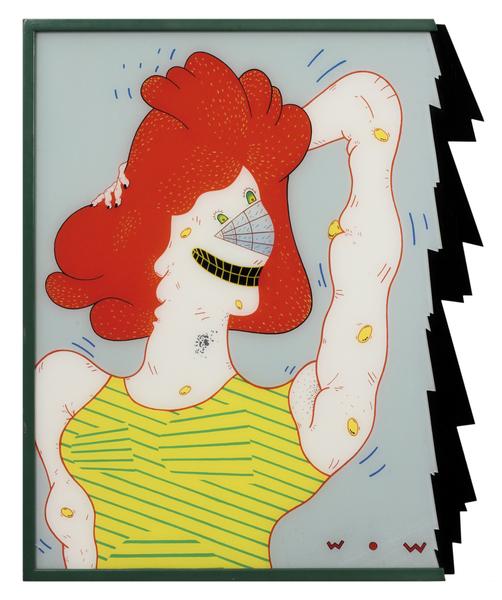

In fact, Saul’s jarring, manic, cartoony style is an apt bridge to connect to this exhibition’s cornerstone movement: the Hairy Who. Besides devising the original furry freak template for outsiders the art world has come to love, the group’s six Art Institute of Chicago grads (James Falconer, Art Green, Gladys Nilsson, Jim Nutt, Suellen Rocca, and Karl Wirsum) enacted some of contemporary art’s weirdest, most enduring visual disturbances. For all of the talk about the group’s reliance on low urges and lumpen sources—common conformisms like comics, advertising, and skin mags—what really sets these artists apart is their insistence on grinding against the grain. In time, that determination produced secret histories and oddball lineages. To use the ironic title of one of Gladys Nilsson’s awesome Plexiglas paintings, the artists in this and other sections of this excellent show were very worldly indeed—just rarely in the way that good taste or the art world demanded.

Roy De Forest, The Young Wordsworth (1963).

Courtesy of Matthew Marks.

Robert Arneson, Untitled (Binoculars) (1965).

Courtesy of Matthew Marks.

Jim Nutt, Wow (1968).

Courtesy of Matthew Marks.

Cary Loren, Mermaid and Angel (Niagara on Set) (1975/2011).

Courtesy of Matthew Marks.

Related stories:

Jeffrey Deitch’s “Coney Art Walls” Exploits Artists for Real Estate Ploy

Doris Salcedo’s Uncanny Installations at the Guggenheim Capture Unspeakable Horrors

Will the Havana Biennial 2015 Be a Bonanza for Cuban Artists?

MoMA Curator Klaus Biesenbach Should Be Fired Over Björk Show Debacle