Art Fairs

Art Dealers at Frieze Masters Are Hustling to Make Sales Despite a Low Supply of High-Quality Works

The fair's VIP preview signaled a cautious moment in the art market.

The fair's VIP preview signaled a cautious moment in the art market.

Julia Halperin

“What brings you here?” a well-dressed man asked Ari Emanuel, the CEO of entertainment behemoth Endeavor, in the aisles of Frieze Masters in London on Wednesday morning. “You know, we own this,” Emanuel replied, arm extended for a handshake.

One might have forgiven the Hollywood executive for skipping the VIP opening this year. Less than a week ago, Endeavor—which owns a 70 percent stake in Frieze’s parent company—abruptly postponed its highly anticipated initial public offering for the second time this year.

But nevertheless, Emanuel was in attendance alongside well-heeled collectors and art-industry veterans including Princess Eugenie of York, actress Keira Knightley, artist Tracey Emin, and curator Tom Eccles.

The scene at Frieze Masters. Photo: Noami Rea.

Aisles were bustling in the first few hours of the fair, but collectors were generally loath to pull the trigger in a moment characterized by uncertainty and caution thanks to Brexit jitters, political tumult in the United States, and unrest in Hong Kong. Another major challenge is supply: both in the London auctions this week and on the private market, there is simply “not that much good material right now,” notes one dealer.

Soon after the doors opened on Wednesday morning, Hauser & Wirth announced the sale of a Cy Twombly oil-and-chalk work on paper from 1968, priced at $6.5 million. Meanwhile, Annely Juda Fine Art sold a petite 1966 bronze by Naum Gabo for £50,000 from its booth dedicated to Russian Constructivists; Galleria Continua sold a 1947 work by the Italian graphic designer Armando Testa for €90,000; and Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert sold works by Peter Phillips, Allen Jones, and Peter Blake for around £100,000 each. Gisèle Croës Gallery sold a pair of large cast-iron basins, Japanese screens, and several other works for prices ranging from €60,000 to €400,000.

At a time of circumspection, “people are looking for work that’s rare, high quality, and correctly priced,” says Nick Olney of Kasmin. The gallery brought one of the more expensive works on offer at Frieze Masters: a lyrical abstract painting by Lee Krasner, Moontide (1961), priced at $10 million. It is one of the few paintings by the American artist that remains in the collection of the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, which consigned it.

Cy Twombly’s Untitled [New York City] (1968). © Cy Twombly Foundation. Courtesy the foundation and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Timothy Doyon.

Plus, because fewer major estates on the order of Rockefeller or the travel magnate Barney Ebsworth are coming to market, dealers and auction-house executives alike are scouting for works piecemeal, often competing with one another for inventory.

“All this museum giving is taking a toll on the quality level” of art available on the private market, says Franklin Parrasch, who sold a sculpture by the late West Coast minimalist Tony DeLap for $85,000, as well as a work by Dennis Hopper, whose paintings the gallery now exclusively represents, for $45,000.

The impact is being felt most acutely at the top end: Total auction sales of works over $10 million dropped by 35 percent in the first six months of this year compared to the first half of 2018, according to the fall 2019 artnet Intelligence Report.

Six- and seven-figure works on offer at Frieze Masters included a Botticelli portrait, said to be the last in private hands, at Trinity Fine Art, priced at $30 million; an embroidered map by Alighiero Boetti that is reproduced on the cover of the artist’s catalogue raisonné for €2.5 million at Tornabuoni Art; and five of the 27 existing works from Joan Miró’s masonite series, priced at $2.5 million each at Nahmad Contemporary.

But perhaps as a result of the supply squeeze, many of the most memorable presentations at the fair are of works that have long been underestimated or overlooked by the mainstream art world, rather than ‘B’ material by familiar blue-chip names. This segment of the market is a specialty of the fair’s Spotlight section, which has been organized this year by Laura Hoptman, the director of New York’s Drawing Center.

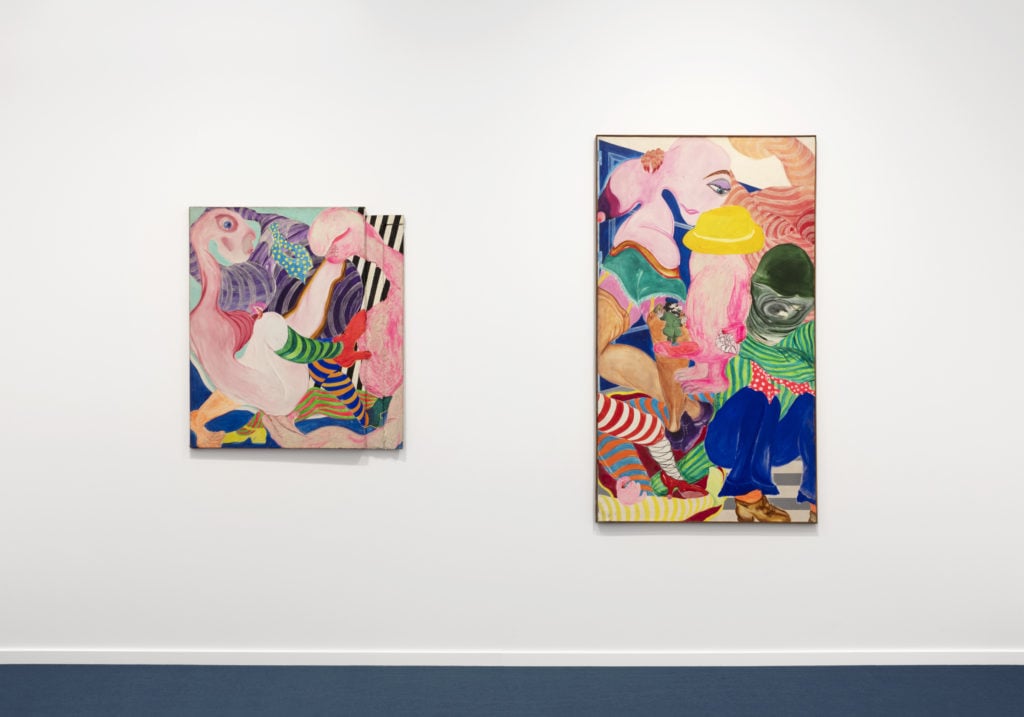

Works by Jacqueline De Jong at Frieze Masters. Photo courtesy of Pippy Houldsworth Gallery.

A solo booth of exceedingly atmospheric black-and-white photographs by the American artist Ming Smith is a particular highlight. Although the artist was the first black female photographer to have a work acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1975, she was largely ignored by the art establishment in the ensuing decades, and does not currently have formal gallery representation. (The Frieze Masters stand is presented by Jenkins Johnson gallery of San Francisco, which also won the Frieze Stand Prize for its display of the artist’s work at Frieze New York and will show her work at Paris Photo next month.)

Another high point is the work of Jacqueline De Jong, an 80-year-old Dutch painter and activist whose irreverent paintings of tangles of stockinged legs and lumpy faces look as if they could have been made last year, rather than in the ’70s. The artist had a solo exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam earlier this year, and her first UK solo show opens next month at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery in London. Her paintings are on offer at the gallery’s Frieze Masters stand for prices ranging from €24,000 to €45,000.

Nam June Paik at Gallery Hyundai at Frieze Masters. Photo by Mark Blower, courtesy Gallery Hyundai.

And although his work is hardly unknown, the late video-art pioneer Nam June Paik offers one of the most heart-pumping presentations in the fair. A solo booth organized by Gallery Hyundai serves as an appetizer for a full retrospective of the Korean-American artist’s work opening at Tate Modern later this month.

Buzzing, towering sculptures assembled from television sets, musical instruments, and other cast-off materials are available for as much as $1.5 million—but Patrick Lee, the gallery’s director, insists the artist’s market has plenty of room to grow. In what could be considered Frieze Masters’ unofficial slogan, he said people may be somewhat familiar with the work—but “he’s under-appreciated still.”

Additional reporting by Naomi Rea.