Market

How Does a Super-Collector Shop at Frieze London? We Tagged Along With Jupiter Artland Patron Nicky Wilson

The Scottish collector takes a surprisingly down-to-earth approach to the art fair.

The Scottish collector takes a surprisingly down-to-earth approach to the art fair.

Javier Pes

Nicky Wilson’s ambitions for art are nothing if not giant-sized. In person, however, she is so down to earth that few would realize that she is one half of a power couple running Jupiter Artland, near Edinburgh, a privately owned sculpture park that welcomes thousands of visitors each year.

For the past decade, the Wilsons have been commissioning leading artists to create site-specific works on the grounds of their home, which is open to the public from spring to autumn, and strives to welcome every school child in Scotland. They even host their own summer music festival, Jupiter Rising.

When collectors are at that level—the Wilsons have their very own, fabulous Joana Vasconcelos swimming pool in their backyard, unveiled this summer—what on earth might they want at Frieze London? artnet News spent a happy few hours visiting the fair with Wilson to find out.

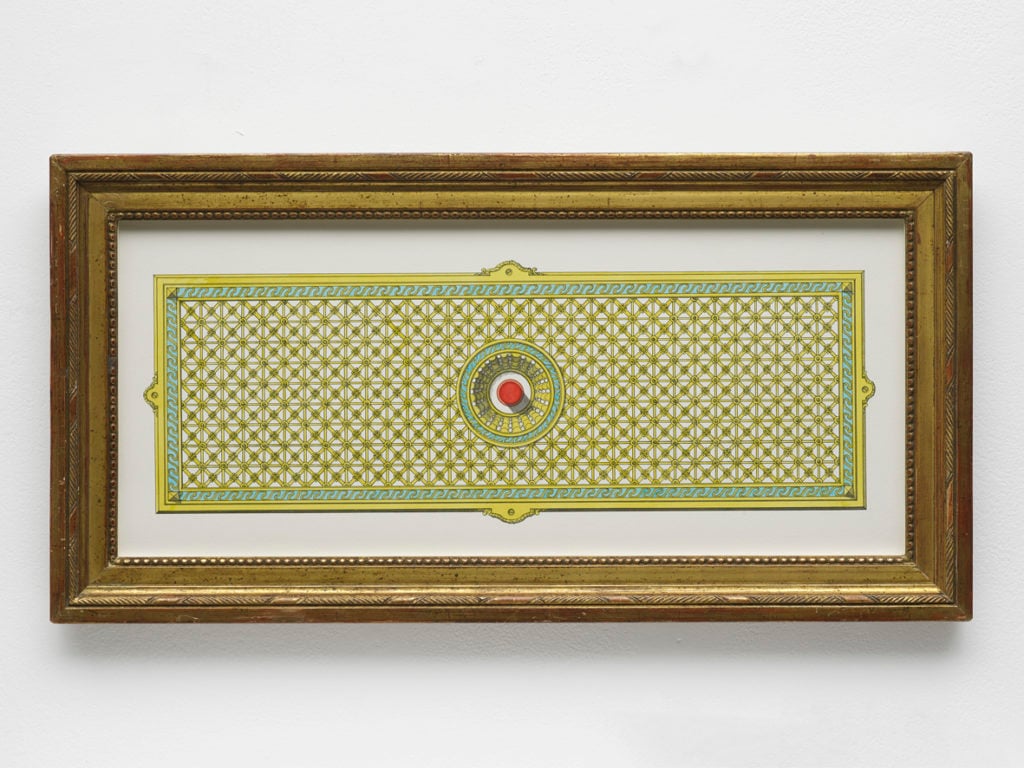

“Art has got to hit me in the solar plexus,” Wilson says, as we arrived at our first booth, Herald St. of London. Pablo Bronstein’s Panic Button in Russian Style (2019) catches her eye, so much so that we go looking in the gallery’s backroom for more by the artist. “There is always something in the gallery’s backroom,” she says.

Pablo Bronstein, Panic Button in Russian Style (2019). Courtesy the artist and Herald St, London. Photo by Andy Keate.

The Wilsons know the Argentina-born artist well. They commissioned his splendid Rose Walk for Jupiter Artland, a delicate Gothic-meets-Chinoiserie structure that houses an actual rose garden. Next stop is Modern Institute of Glasgow. “I’ve got to support Scotland,” Wilson explains. The gallery represents the Scottish artist Jim Lambie, who has transformed an outhouse turned shop at Jupiter Artland by cladding it in aluminium with multicolored trim. It looks irresistible and alien in a friendly way.

The Wilsons want the artists they chose for their park to create not necessarily their biggest work, but rather help them create one of their best works. Those who also risen to the occasion include Charles Jencks, Andy Goldsworthy, Cornelia Parker, and Lambie, as well as a host of artists lesser known on the international stage, such as Tania Kovacs, Laura Ford, Nathan Coley, and Peter Liversidge, showing their independent streak.

Nicky Wilson (left) with the artist Phyllida Barlow in 2018. Image by Anna Kunst courtesy Jupiter Artland.

Jupiter Artland’s highlights also include Phyllida Barlow’s first permanent outdoor work, a monumental piece that towers in the sculpture park’s woodlands. Barlow taught Nicky Wilson when she was an art student at Camberwell College in South London. The artist says Wilson was “a wild one.”

Mid-morning we bump into another of Wilson’s friends, also a former tutor: the artist Cornelia Parker. She has two works at Jupiter Artland.

The impromptu gathering is something of a reunion. We’re at the booth of Edinburgh gallery Ingleby, and gallerists Richard and Florence Ingleby have known the Wilsons since they arrived in Edinburgh 20 years ago. There is much talk of children, A-level results, an offspring’s first job in the art world, and so on.

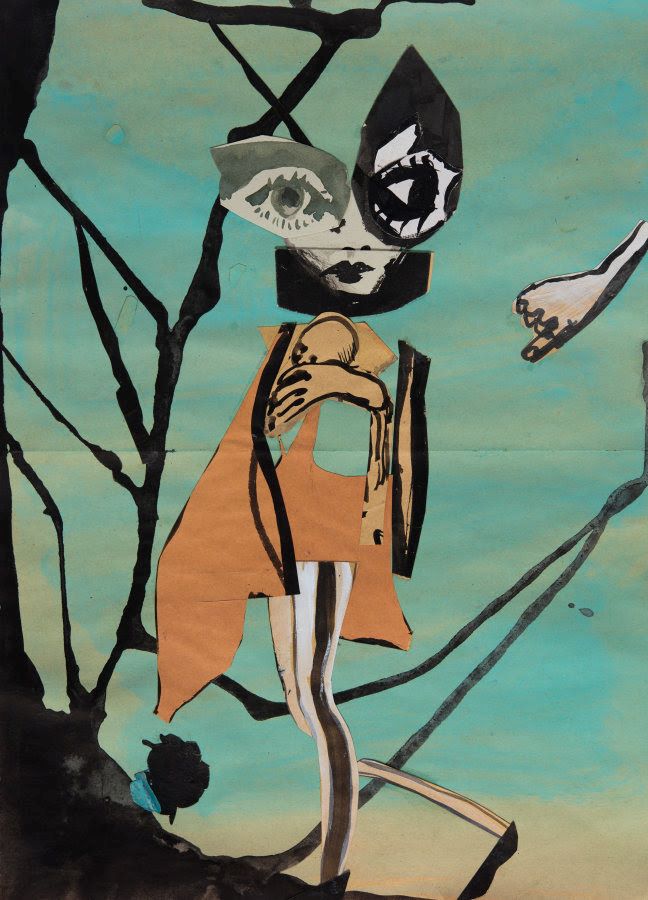

Moyna Flannigan, Tear 54 (2019). Copyright the artist, courtesy of Ingelby Gallery.

At the Ingleby booth, the Scottish artist Moyna Flannigan’s new painted collages are an instant subject of conversation between gallerists and collector. One new work in particular, showing a mother and child, titled Tear 54 (2019) and priced at £3,500 (£4,300), impresses Wilson partly because it signals a change in the artist’s work, which she knows well.

Indeed, Wilson reveals that Flannigan, who seems to be enjoying a happy mid-career, has already painted her portrait—albeit in a startling way. “I am shown breastfeeding a donkey,” she says, raising her eyebrows.

The symbolism may be opaque, but the anecdote conveys Wilson’s sense of humor and love of colorful, off-the-wall art—and her longstanding support of female artists. She makes a beeline for Virginia Overtones work at White Cube. (You can feel a major commission over the horizon.) At Hauser & Wirth, Wilson lingers before a wall of paintings by Louise Bourgeois. “In my dreams…” she says with a sigh. The Nicky and Robert Wilson have been ploughing the profits from their homeopathic medicine business into their art collection but some works at the fair are beyond their price points.

As art museum directors and their trustees on both sides of the Atlantic talk about about tackling gender bias, the Wilsons have been walking the walk for years. The sculptor Laura Ford, whose work was on show at Frieze Sculpture last year, says they backed her to the hilt when she proposed a series of “Weeping Girls” for Jupiter Artland. Ford’s melancholic figures seem like lost souls in the woods.

“We were mainly British but as we are opening up to more international artists,” Wilson explains. “What remains the same is our interest in women.”

Italian artist Lara Favaretto is the latest to draw her eye. She has works in Ralph Rugoff’s main exhibition at this year’s Venice Biennale, which Wilson has come from seeing. At Frieze, Favaretto’s swirling sculpture made from carwash brushes catch Wilson’s eye at Turin’s Franco Noero.

Lara Favaretto TABOO (2017) at Galleria Franco Noero. Photo by J. Pes.

“There is something mesmeric about them,” Wilson says. She is interested in the ideas behind the work, TABOO (2017), as well as practical details: “Do you get replacement brushes?” A gallerist explains that you do, and the two browse the artist’s similar works on an iPad.

Frieze seems to be for browsing not snapping up works. The Sunday Art Fair is also on her schedule this week. Still, Nicky and Robert Wilson usually buy something during Frieze week, typically for their “private” collection of indoor pieces for their home at the heart of Jupiter Artland.

Hence her interest in Bronstein’s new work, or another artist whose work they already own, the increasingly in-demand Zanele Muholi. A striking new photographic self-portrait of the South African catches Wilson’s interest on the busy Frieze London booth of Stevenson of Cape Town and Johannesburg. (Prices start at $9,000.)

The booth of Stevenson Gallery at Frieze Art Fair 2019, London, UK. Photo by Nylind, courtesy Frieze Art Fair.

Yet art fairs can also be the start of a conversation that pays off later, Wilson says. After we part, she is due to meet one of the doyennes of the London art scene, dealer Maureen Paley, to talk about possible major commission. When it comes to initiating such a new major commission, Wilson says, “gallerists usually just say ‘get on with it.'”

Zanele Muholi, MuMu XIX (2019). Copyright the artist. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York.

Many of the artists that the Wilsons have selected over the years are now friends of the family. These include the hot-as-Hades Swiss artist Nicolas Party, who has just joined the roster of Hauser & Wirth. The New York- and Brussels-based artist designed Café Party at Jupiter Artland. Unveiled in 2017, the Wilsons joke they would be unable to afford it now given the way that the artist’s prices have skyrocketed.

We checked out Party’s new sculptures of a giant head (at Xavier Hufkens of Brussels) and reclining body (at Modern Institute, Glasgow), both of which are the subject of much collector and institutional interest. I wondered how Wilson felt about collector-investors clamoring to jump on the Party bandwagon.

“His market value is irrelevant,” she says. “I am really pleased at his good fortune. He is more than capable of coping.”

Joana Vasconcelos Gateway (2019). Image by Allan Pollok-Morris. Courtesy Jupiter Artland.

Even amid the glamorous frenzy of Frieze, Wilson’s thoughts are never far from home—in particular because she has spent the past three weeks in Venice visiting the biennale along with her small dog, Daphne. (“She went everywhere. We were normalized,” she says.)

In fact, her thoughts were already turning to the weather back in Scotland. “There is a storm coming,” she says. As Frieze gets into full swing down south, Jupiter Artland is going into winter hibernation: Vasconcelos’s funky pool needs draining, Marc Quinn’s sculpture needs protecting, and no doubt a hundred other things need sorting.