Everyone knows that an online art fair can never fully replace the real thing. But no matter how much analysis a journalist does from a distance, nothing could reveal the strengths and shortcomings of the attempt more vividly than a two-hour screen-sharing experience with a veteran collector on opening day of the first-ever Frieze Viewing Room.

Fortunately, Chris Birchby was game for the virtual ride-along. Now known as the San Diego-based founder and CEO of COOLA LLC, a flourishing organic skincare empire that contains the upscale COOLA and accessible Bare Republic brands, Birchby entered the first online Frieze week hoping to thoughtfully expand his collection of more than 100 works. His journey to accomplishing this goal gave Artnet News a view of how much—and how little—changes when a premier art fair is forced to pivot to an online-only existence.

The good news for the art market? For dedicated collectors, a virtual art fair can still create the sense of competitive urgency that drives many transactions at physical fairs, and UX (user experience) design doesn’t have to be flawless to chisel away any remaining obstacle to transacting remotely.

The less good news? Speedy communication with clients needs to be considered a much higher priority by fairs and exhibitors alike if the format ever hopes to hit escape velocity at scale. And the current virtual infrastructure offers only a shadow of the sense of spontaneous discovery that keeps open-minded buyers roaming the aisles at live fairs.

Carrie Moyer, Neapolitan Projection, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and DC Moore Gallery, New York.

Early Engagement

Although Birchby didn’t know exactly what to expect from a top-tier virtual fair—he’d skipped the online sales platform rolled out to replace Art Basel Hong Kong in March—he did know exactly how he wanted to approach the event. He’d assembled a budget and targeted a handful of artists in the lead-up to the fair based on PDF previews, but he also held out hope for serendipitous additions, especially by emerging young painters—though he stressed that tactic was absolutely not about any financial motivation.

“I’m not out here to pick stocks,” explains Birchby, wearing a Bare Republic t-shirt in his home office. “I want to support the artist while they’re trying to break into the art world and make a career. There’s a mission-based quality [to my collecting] that I enjoy.”

Birchby understands the young artist’s struggle firsthand. After earning an MFA from ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena in 2001, he funded years of striving as a painter in downtown Los Angeles largely by excelling at online poker. (A fragment of one of his own canvases is visible behind his task chair in the Zoom window.) And while his painting practice eventually took a backseat to more classical entrepreneurship, his past experience in the studio and his deep knowledge of the medium’s history continue to guide his collecting today.

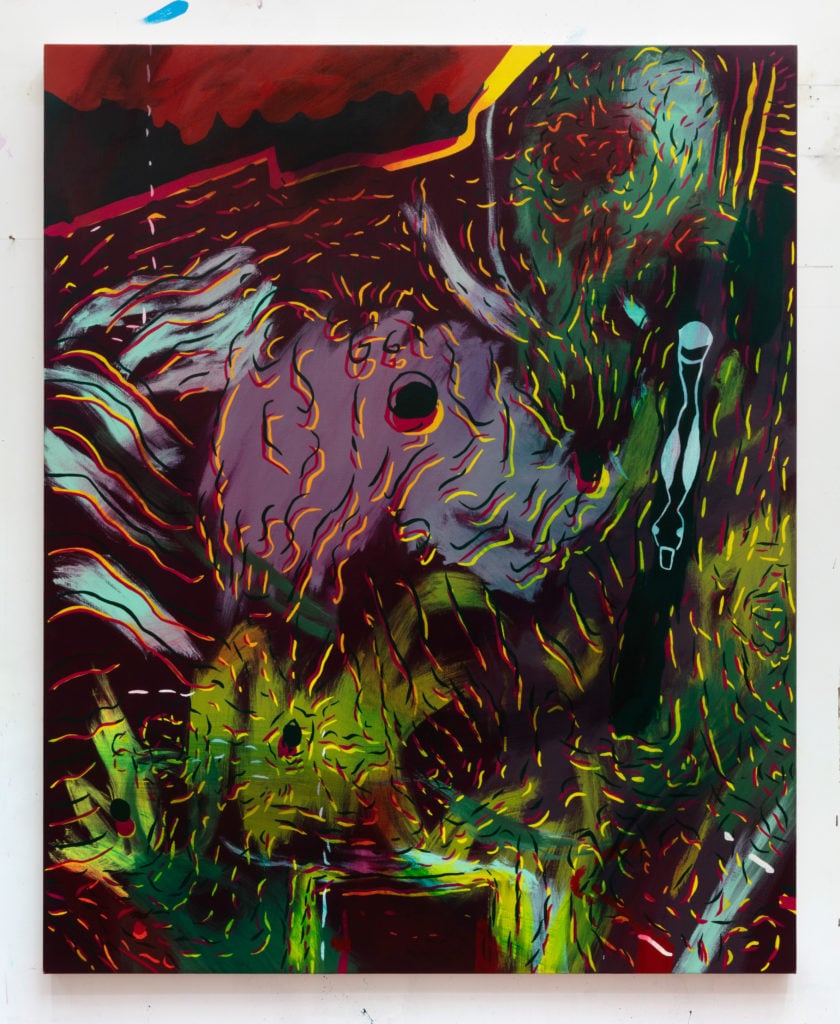

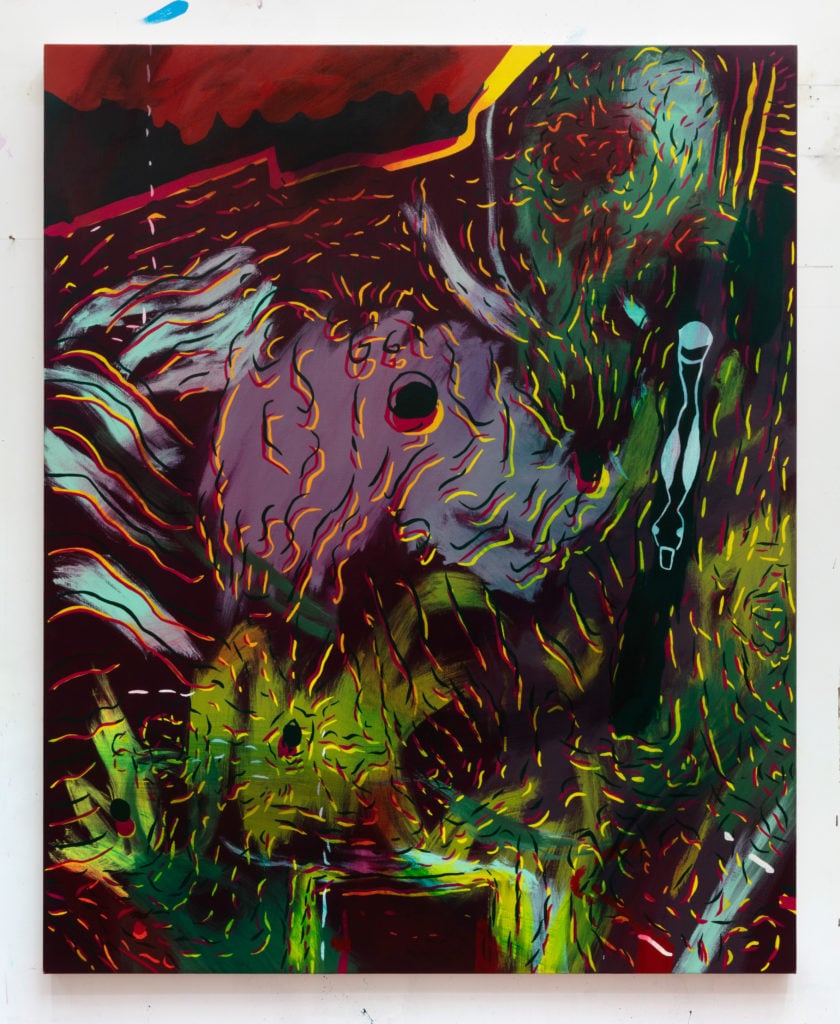

Birchby proves as much with his first acquisition from a Frieze exhibitor—a deal that confirms pre-selling has very much survived the fair sector’s transition to online-only. In a call with Artnet News three days before the viewing room opened to VIPs, he’d signaled a strong interest in the new Carrie Moyer paintings that would be shown by DC Moore Gallery because the artist had been “very influential” to him in his own painting career. Shortly after reconnecting on preview day, he announces that he already reached out to the gallery and acquired Neapolitan Projection, a lush canvas melding hard-edged abstraction with streaks and imprints recalling coral lifeforms, priced at $65,000.

After logging into the viewing room, Birchby clicks into DC Moore’s digital booth to scroll through and admire Moyer’s works again. “I’ve been looking for the right [piece] of hers to live with for a while,” Birchby says. When Neapolitan Projection arrives, he plans on installing it in his home near works by Katharina Grosse, Bernard Frize, and Joanne Greenbaum to “tell a nice story of non-representational painting.”

From DC Moore, Birchby clicks over to Various Small Fires, the innovative Los Angeles and Seoul-based gallery he knows well. Here, too, he’s finalized two acquisitions prior to VIP preview day: Joshua Nathanson’s Fight or Flight, a quietly hallucinatory oil-on-canvas that floats between figuration, landscape, and abstraction, priced at $24,000; and a small photorealist painting by Calida Rawles depicting a young girl in a white dress eerily suspended underwater, priced at $15,000.

His pride in his new purchases is palpable through the software. But with the pre-existing deals now covered, it’s time to venture into the digital unknown.

Joshua Nathanson, FIGHT OR FLIGHT, 2020. Courtesy of Various Small Fires, Los Angeles and Seoul.

Two Steps Forward, One Step Back

Birchby returns to the Frieze Viewing Room’s main galleries page and scans through the exhibitors somewhat at random, as much to get a feel for the online architecture as to see what other works might interest him. A few days earlier, he’d wondered how robust the user experience would be. He’d even mused about the future potential for a game-ified virtual-reality art fair where collectors would have to outpace each others’ avatars to secure first dibs on prized works.

Now that he’s merely free-scrolling through an alphabetized grid of galleries, though, his brow furrows. “I don’t really see how this is any different from browsing a normal website….”

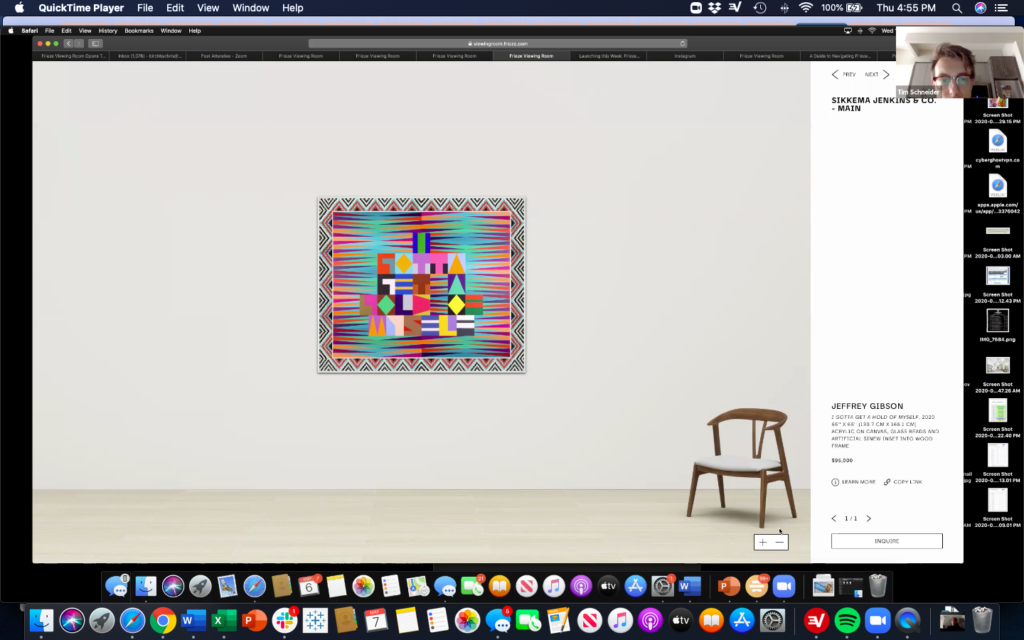

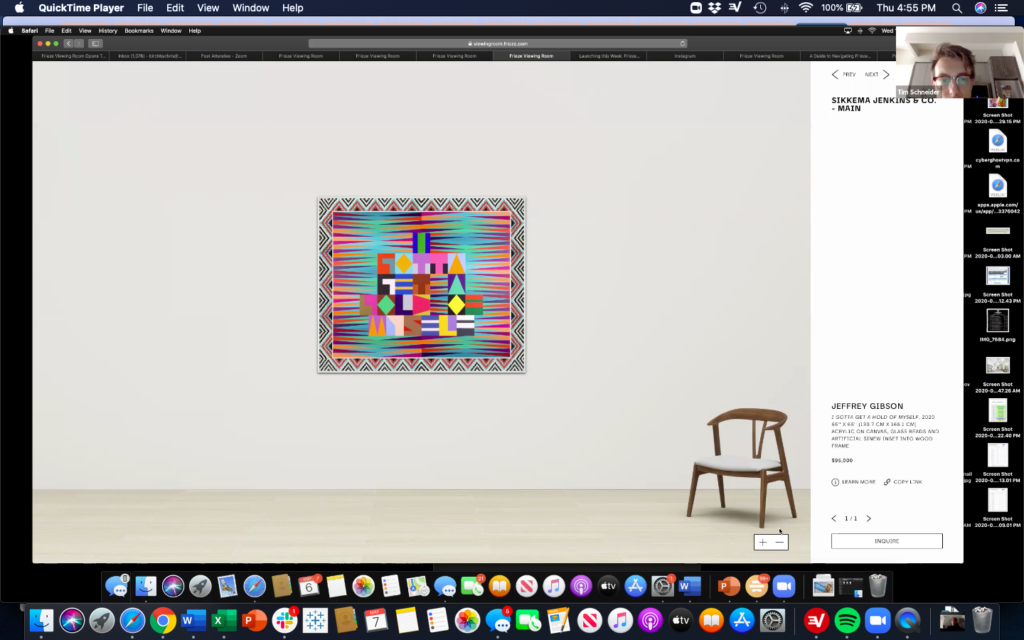

However, he brightens a bit upon encountering a vibrantly colored text painting by Jeffrey Gibson. Since this is the first time he’s fully clicked through to a single work—he only reviewed his early acquisitions within the grid view of available pieces on each gallery’s individual page—it’s the first time he’s seen the “to-scale” view in Frieze’s online interface. Here, the piece appears on a white wall with an empty modernist chair in frame as a size reference.

The shared screen experience of the Frieze Viewing Room, featuring a scale view of a Jeffrey Gibson painting at Sikkema Jenkins & Co. Courtesy of Chris Birchby.

“Oh, beautiful that it comes up like that.” He zooms in on the piece using the site’s controls. “They just Photoshopped that all in [on the wall]—you can see how even it is on the edges there,” he says, a line meant as an appreciation of the execution, not a criticism. Here, at least, is something he can’t get in a PDF.

Birchby also commends Frieze and the exhibitors willing to openly display pricing and availability for the works on view, noting that dealers are “usually a closed book on that front” at live fairs. But a bit of confusion bubbles up when he tests out the fair’s search function. After filtering out all works except those in the price bracket between $20,000 and $50,000, he notices some paintings that carry no listed price at all, as well as a few others that merely reiterate the price range he’s selected in the menu.

“Just $20,000 to $50,000? That’s a big range,” he says. With a grin, Birchby uses a comparison to explain why he sees price ranges as self-defeating to sellers in any context. “In California real estate, if a house is listed at $1 million to $1.25 million, you just say, ‘It’s a million-dollar house.’” Good luck trying to get a buyer to go higher.

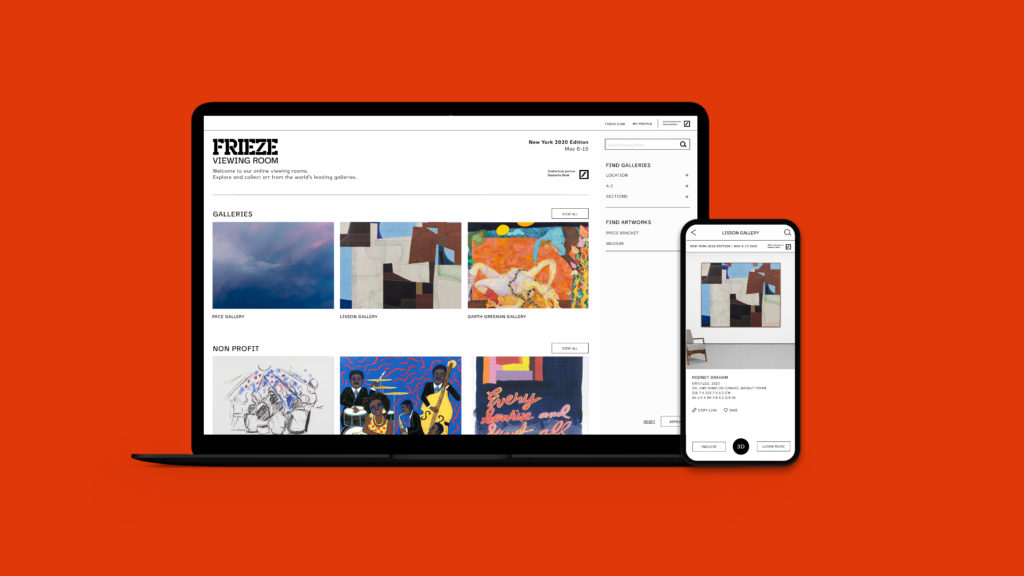

Courtesy of Frieze.

Real Life Asserts Itself

Although Birchby states that he’s not looking to buy more beyond his three pre-fair acquisitions, he continues exploring what Frieze has to offer, including works at PPOW and the fair’s nonprofit sections benefiting public-health causes. He has a bit of flexibility thanks to a savvy recent business move.

While COOLA and Bare Republic’s shared foundation is organic sun-protection products—a category poised to decline due to the global collapse in travel and outdoor activity in the social-distancing era—the “new normal” compelled him and his team to whip up Bare Hands, a quick-drying hand sanitizer made with natural ingredients, in a small fraction of their normal product-development timeline. Sales of the new item have been strong enough that Birchby has even been hiring new staff instead of having to cut back during the crisis.

Despite a mission to keep browsing, though, Birchby’s energy is starting to wane after an hour of click-and-scroll. “I don’t know if my patience is here to spend as much time as I would at the real fair,” he admits. “I can hear my kids in the other room, and I know I have work to do.” It is, after all, the middle of a Wednesday.

Most likely, he says, he’ll “come back and click around at night with three or four other [browser] windows going, so it’s not total focus.” This is a natural, and perhaps insurmountable, hurdle for a live event that has suddenly had to transform into an e-commerce platform beamed into home offices everywhere.

Another such hurdle emerges when Birchby grins and looks away from his screen toward the tiny voices rising in volume over the Zoom connection. “Oh, the kids found me!”

What ensues is the toughest negotiation Birchby encounters during his time in the Frieze Viewing Room: with his diaper-clad son, Wilder, bouncing on his lap, his not-quite four-year-old daughter, Bellemy, tries to convince her dad to give up on the art fair so she can watch My Little Pony.

Delighted but not deterred, Birchby instead tries to interest Bellemy (who, it turns out, has used markers to apply Ziggy Stardust-like streaks of bold color across her eyes) in the onscreen grid of works by emerging painters. “Which of these is your favorite?” he asks.

“None of them!” Bellemy exclaims, gesturing at Birchby’s second monitor. “My Little Pony!”

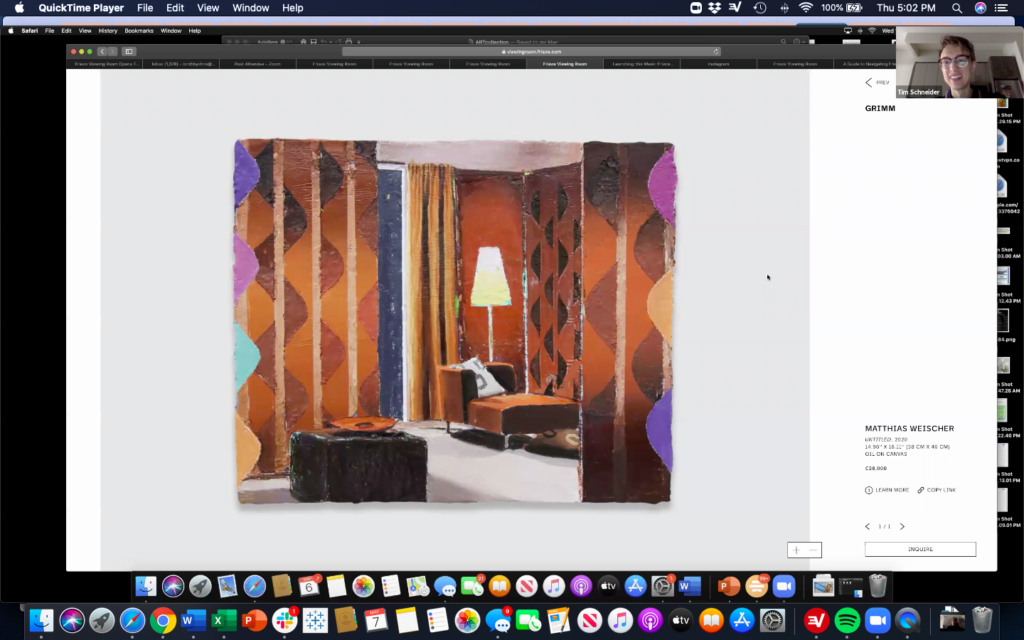

The shared screen experience of the Frieze Viewing Room, featuring work by Matthias Weischer at GRIMM. Courtesy of Chris Birchby.

Winding Down

Although AJ, Birchby’s wife, soon retrieves the kids—and stops to admire a small, texture-heavy painting of a retro home interior by Matthias Weischer at GRIMM—it’s clear the collector is nearing the saturation point. He browses for a while longer, including using the site’s messaging capabilities to inquire about young figurative painters Sedrick Chisom and Trey Abdella with Matthew Brown and T293 Gallery, respectively. (All of Abdella’s works are already marked as sold or reserved by then, but the Chisom canvas appears to still be available.)

However, responses aren’t forthcoming from either gallery. Birchby laments the absence of a real-time chat function like you now find on nearly every e-commerce or customer-service website outside the art market. The problem isn’t just the inconvenience; it’s also the way it turns the social, dynamic aspect of meeting a dealer inside a booth or gallery into an impersonal, closed-ended query. In this setting, you’re unlikely to be led from your interest in one work to your interest in something completely different through the magic of live conversation.

“This is the stage at a real fair where I’d be looking for a sandwich or a cocktail,” Birchby says with a laugh just after passing the two-hour mark. He’s ready to sign off, but he’s satisfied. After having seen so much other work, he says there’s nothing he would have wanted more than the three pieces he acquired before the viewing room opened.

In a later email exchange, however, Birchby confirms that he did in fact return later on in the preview. While he was disappointed that he still hadn’t received a reply from either Matthew Brown or T293 by noon Eastern Time Thursday (the former did eventually write back with apologies that the Chisom had already found a buyer), he had discovered a delicate but humorous painting of the grim reaper beckoning to a disobedient dog by Sanam Khatibi at Rodolphe Janssen overnight. After the gallery responded to his inquiry, he was delighted to quickly finalize the acquisition, proving that small discoveries aren’t completely off the table even when fairs are forced to go digital—and even when Death himself, however whimsically rendered, is directly involved.