People

‘I’m Always in a Recession’: A Day in the Life of Collector-Provocateur Stefan Simchowitz, Who Feels Just Fine Doing Business During Lockdown

Simco takes Artnet News along for the ride as he wheels and deals from home in LA.

Simco takes Artnet News along for the ride as he wheels and deals from home in LA.

Naomi Rea

Days start early for the controversial art collector and cultural entrepreneur Stefan Simchowitz.

On a recent Wednesday at the end of April it is even earlier than usual. He is roused at 3 a.m. when his son crawls into bed between him and his partner, Rosi Riedl. It is already a full house. Sandwiched together with two stubborn rescue dogs, Benji and Sambuca, he struggles to get back to sleep. The art collector-slash-dealer-slash-patron has a lot to think about.

His reputation for flipping young artists at auction has made Simchowitz—Simco to those in the know—a thorn in the side of the art world establishment. But these days, he says he’s not concerned with selling art. His venture instead hinges on the production of work by young and emerging artists, on whom the public health situation has had an outsize impact. Many are struggling to make rent or keep their studios running, and he is busy coordinating to keep them afloat.

“I think it’s inappropriate to try and sell art right now,” he says. “First of all, clients don’t pay for work on a regular basis, which is no help to artists who need cash. And secondly, everyone is under pressure, so it’s a very difficult thing to call a friend who owns a restaurant and ask them to buy art. It’s ridiculous.” Besides, he says, the people who are buying right now are only interested in assets that are speculatively of monetary value, which isn’t generally the case for young artists with no established market.

Rosi Riedl, Morris, dogs Benji and Sambuca, and baby Harlow, the child of Lisa Marie Pomares and Oscar Murillo. Photo courtesy Stefan Simchowitz.

I’m tailing Simchowitz remotely, to get a fly-on-the-wall perspective on his daily life. Surprisingly little has shifted in his day-to-day since Los Angeles was ordered to shelter in place in March. “Even when I was in the movie business, my office was my home, it’s my comfort zone,” he says.

As the art world’s resident enfant terrible, Simchowitz tends to eschew the industry’s usual protocols. He’s not one to get invited to gallery dinners, nor does he jetset with the fashionable set. When he would go to art fairs, he would routinely upset gallerists by stomping around asking for big discounts.

As for the economic impact of the current crisis, Simchowitz is not too perturbed. “I’m always in a recession,” he says. “In a week I give $10,000 to artists, to buy their work and keep them alive.”

He takes the opportunity to sound off about the poverty of working capital for artists in the traditional art market system. “As much criticism as I get for sometimes selling a work at auction”—in February, he sold a painting by the 35-year-old Ghanaian artist Amoako Boafo at auction for more than 10 times its high estimate—“I support artists all over the world who have no markets on a consistent basis and it makes a huge difference,” he says.

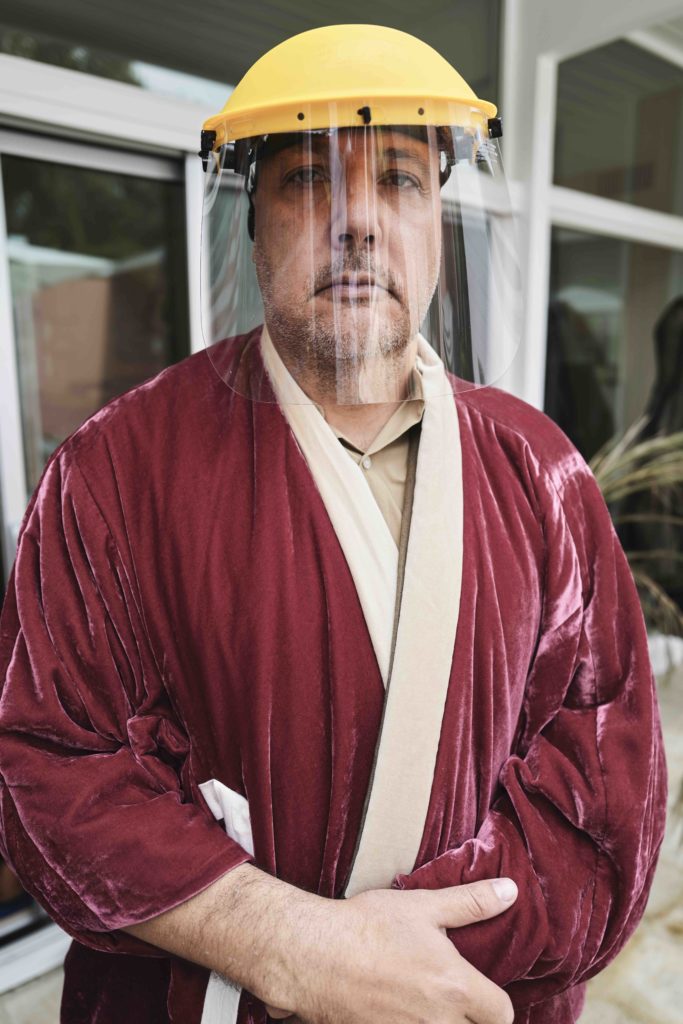

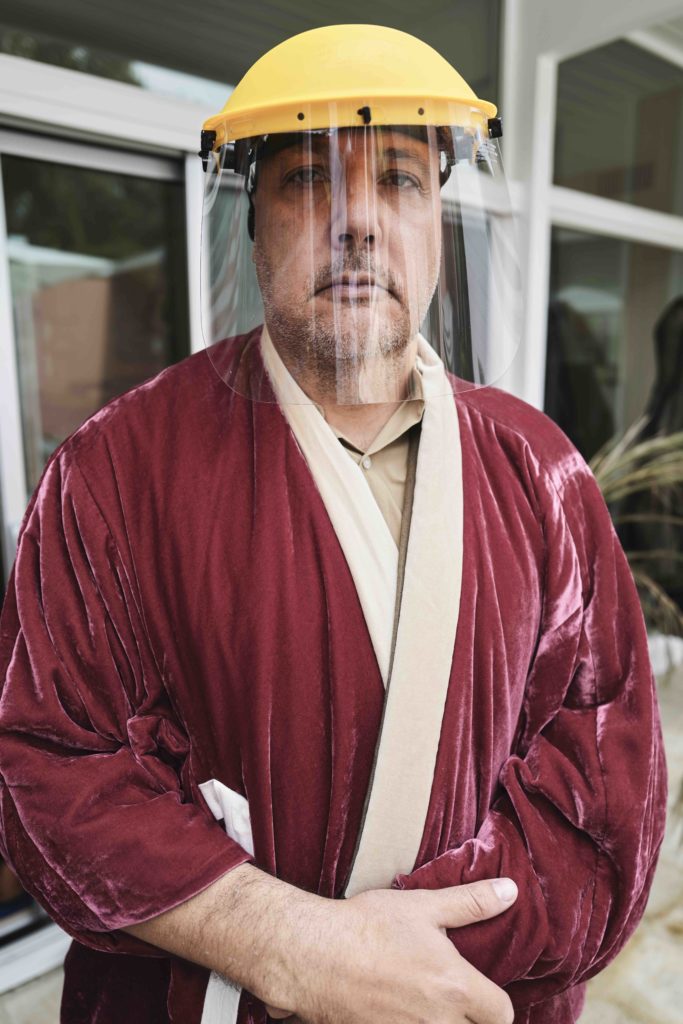

Stefan Simchowitz walking. Photo courtesy Stefan Simchowitz.

After a few hours of tossing and turning, Simchowitz decides to give up on sleep. It might be 5 a.m. in Los Angeles but there are plenty of time zones that have been up and at ‘em for hours. He brushes his teeth—the 49-year-old never eats breakfast—and washes down his morning vitamins (a Vitamin B12 spritz, a D3 + K2 complex, and something called Elysium, which he tells me “supposedly makes you younger”) with a bottle of San Pellegrino.

Then he dons one of the many headsets that are scattered around his house and goes for a walk around his neighborhood in Malibu West, which he calls “deep Malibu.” Walks are an important part of the Simco ritual. Inspired by the Greek philosopher Socrates, who was known for his walking-and-talking approach to philosophy, he tells me earnestly that he has averaged six miles a day over the past five years. “If you ever have a meeting with me, I’ll tell you to wear tennis shoes, because we’re going for a walk.”

First up, he calls an artist he works with in South Africa. While Simchowitz tends to favor artists who are prolific producers, she is struggling to monetize her inventory, as there is a lot of unpaid for work that has been consigned to different galleries. They discuss her career, and Simchowitz agrees to send her $1,000.

After that, he speaks to a couple of friends. One is stuck alone in Paris, another in London. Then, he gets on the phone with New York; there is a show by Petra Cortright, an artist who Simco “discovered” and purchased many works from early on, at Team Gallery that needs to be taken down, and with limited movement during the lockdown, and 100 huge printed sheets to be deinstalled, the logistics are challenging.

Stefan Simchowitz’s house. Photo courtesy Stefan Simchowitz.

Back home, after crawling back into bed for a bit, he goes on Instagram to promote a talk he has planned for later in the day. Simchowitz was an early adopter of social networks as a tool for business, and he spends between two and three hours a day on the photo-sharing app. “You’ll never hear me say ‘I need to get off social media,’” he says.

There are other items of business to attend to, some of which are overseen by his partner Rosi, but there is another important “member of his tribe,” as he puts it: his right-hand woman, Lisa Marie Pomares. The former model and her newborn baby girl, Harlow, is quarantining with them. Simchowtiz is the child’s Godfather, and the father, art market darling Oscar Murillo (who is one of the artists Simchowitz is known for buying early and cheap) is in Colombia.

Stefan Simchowitz’s house. Photo courtesy Stefan Simchowitz.

The house, which Simco bought at the end of last year, is filled with art. On one side of the living room is a bookshelf, decorated among other things with some artwork by Jonathan Edelhuber. A gorgeous table by the architect and furniture designer Mira Nakashima, daughter of 20th-century American furniture designer George Nakashima, is in the center of the room. Tripping around a mess of empty delivery boxes is another of Simchowitz’s adoptees, a former alleycat named Smokey.

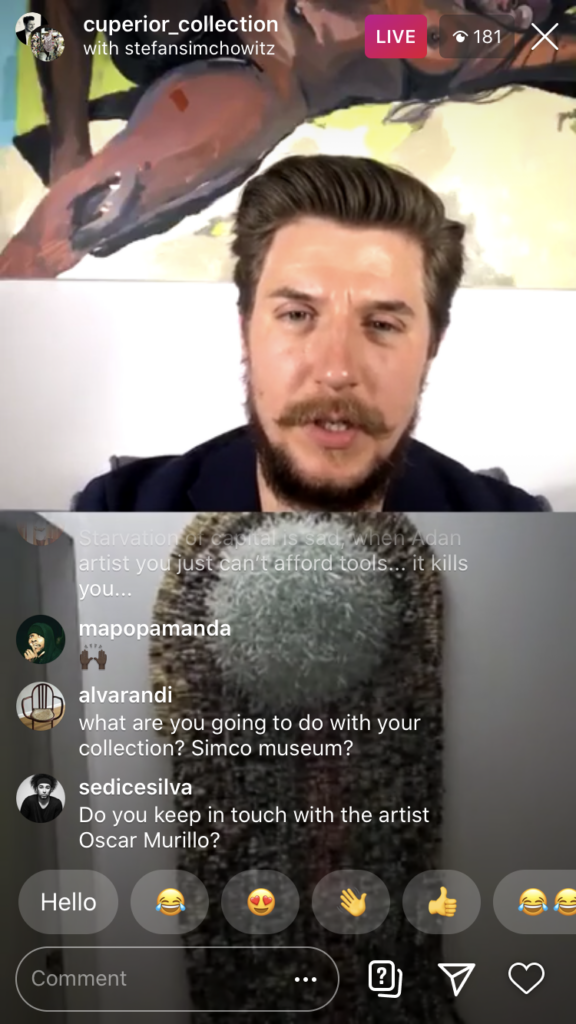

At noon, Simchowitz goes live on Instagram with Oliver Elst, the German car designer and art collector behind the Cuperior Collection.

In the nearly two-hour conversation, Simchowitz spends most of the time shouting out his artists and proselytizing to his followers about his collecting philosophy. He has around 83,000 of them on Instagram, and there are consistently some 200 concurrent viewers.

Screen shot of Stefan Simchowitz and Oliver Elst on Instagram Live.

When asked, he reveals that he has no plans for a “Simco Museum,” but will leave his extensive collection to existing museums. He says he has already given $10 million of work to museums, listing off the Brooklyn Museum, MOCA, MCA Chicago, the Pérez Art Museum Miami, and the Tang Museum, among others. And his advice to young artists? “Number one: be good. Number two: call me.”

Ken Taylor in studio. Photo by Stefan Simchowitz.

Lunch is a vegetable burrito with guacamole from Lily’s, and a cold brew from the fashionable LA coffeehouse, Blue Bottle.

Then, Simchowitz drives out to visit his own residency program in Pasadena, where the artist Ken Taylor is on an extended residency, and Jesse Edwards is doing a ceramic residency (the residency has three kilns on site, as well as a giant hand loom).

Sayrle Gomez in his studio. Photo by Stefan Simchowitz.

After leaving Pasadena, Simchowitz swings by the studio of Marc Horowitz. Then, he pays another studio visit to Sayre Gomez—a California artist who shows with François Ghebaly—and takes a portrait of the artist wearing a mask.

“I have a big passion for photography, on every level,” Simchowitz says. The hobby surprises some people because he doesn’t fit into most people’s “moral idea” of what a good photographer should look like, he says.

Inspired by artists like Deana Lawson and Wolfgang Tillmans, he makes time to take photographs every day. “Even if my life is quiet and banal, it is my experience,” he says. “The job of every photographer is to photograph your world.” (Los Angeles dealer David Kordansky has expressed interest in Simchowitz’s work.)

Stefan Simchowitz’s bookshelf. Photo courtesy Stefan Simchowitz.

The evening is fairly quiet. Simchowitz eats nothing for dinner, except a bag of Rusty’s salt-and-pepper chips, which he deems the “best in the world.”

He didn’t go out to fancy dinners or parties even in the “before time,” so you won’t catch him on the art world’s favorite online hangout, Houseparty. The only special occasions are Friday nights, when he will have Shabbat with his family (lately they’ve been doing it over Zoom).

Instead, he spends his evening reading books. He dips into a series of essays about the political economy of art edited by the art historian Julie Codell. He is also taking an online course on the ancient Chinese philosopher Confucius, and is studying the Analects, Confucius’s daily teachings, which were recorded by his students.

By the time he falls asleep at 3 or 4 in the morning, he has a lot to think about.