The Gray Market

How to Avoid the Worst Traps of the A.I.-Assisted Artwork Debate

Our columnist consults with two visionary artists on the hottest topic in art and tech: what is the future of A.I.-assisted artwork?

Our columnist consults with two visionary artists on the hottest topic in art and tech: what is the future of A.I.-assisted artwork?

Tim Schneider

Every Wednesday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, sledding the uncanny valley…

In the borderlands between art and tech, no single development has sucked up more oxygen since late spring than the rise of DALL-E and other A.I.-driven text-to-image generators. Once a fringe experiment whose results were more interesting for their flaws than their fidelity, algorithms like these have dramatically escalated in quality, speed, and public reach in 2022.

But while resistance to their use is mounting in domains ranging from the foreseeable to the surprising, it’s increasingly clear that many opponents of the technology don’t understand what, exactly, they’re protesting against. Worse, the dust being kicked up by the conflict has made it harder to see the most important ways A.I. is already pushing the process and business of image-making across borders it’s unlikely to ever retreat behind again.

If your media intake has been inundated by either straightforward news stories on DALL-E and its ilk or the actual madcap imagery they can create from prompts like “U.S. founding fathers parkour tournament,” skip the paragraph after this one. If you need a primer, well, here we go.

Text-to-image-generators work by being “trained” to analyze, construct, and deconstruct images tagged with descriptive terms through extreme repetition (meaning datasets made of hundreds of millions of reference points). Over time, the underlying algorithms have become powerful enough to produce high-fidelity, high-precision outputs from users’ written prompts in seconds. The result? Even novices now have an unprecedented ability to conjure up as much custom imagery as their time and budgets allow.

The true step-change in the rise of text-to-image generators has been in their uptake. Last month, OpenAI, the Microsoft-backed startup behind DALL-E, expanded from a waitlist-only limited release to full public accessibility. The company stated at the time that the software’s 1.5 million users were leveraging it to generate two million images a day. Hundreds of thousands or millions more daily visuals are also being churned out by users of publicly available competitors Midjourney and Stable Diffusion, as well as more tightly guarded rivals from Google (Imagen), Meta (Make-a-Scene), and (it’s rumored) Amazon and Apple, to name just the headliners.

The totality of this output raises a stunning prospect: humankind seems to be on pace to regularly produce more images with A.I. assistance than without it—if we haven’t passed the tipping point already. The shift applies to more than just static images, too. Several startups and tech giants alike are powering up algorithms to generate high-quality video and 3D-rendered animations from text prompts. (Algorithmic outputs for music and natural language, a.k.a. writing and speech, are even further along.)

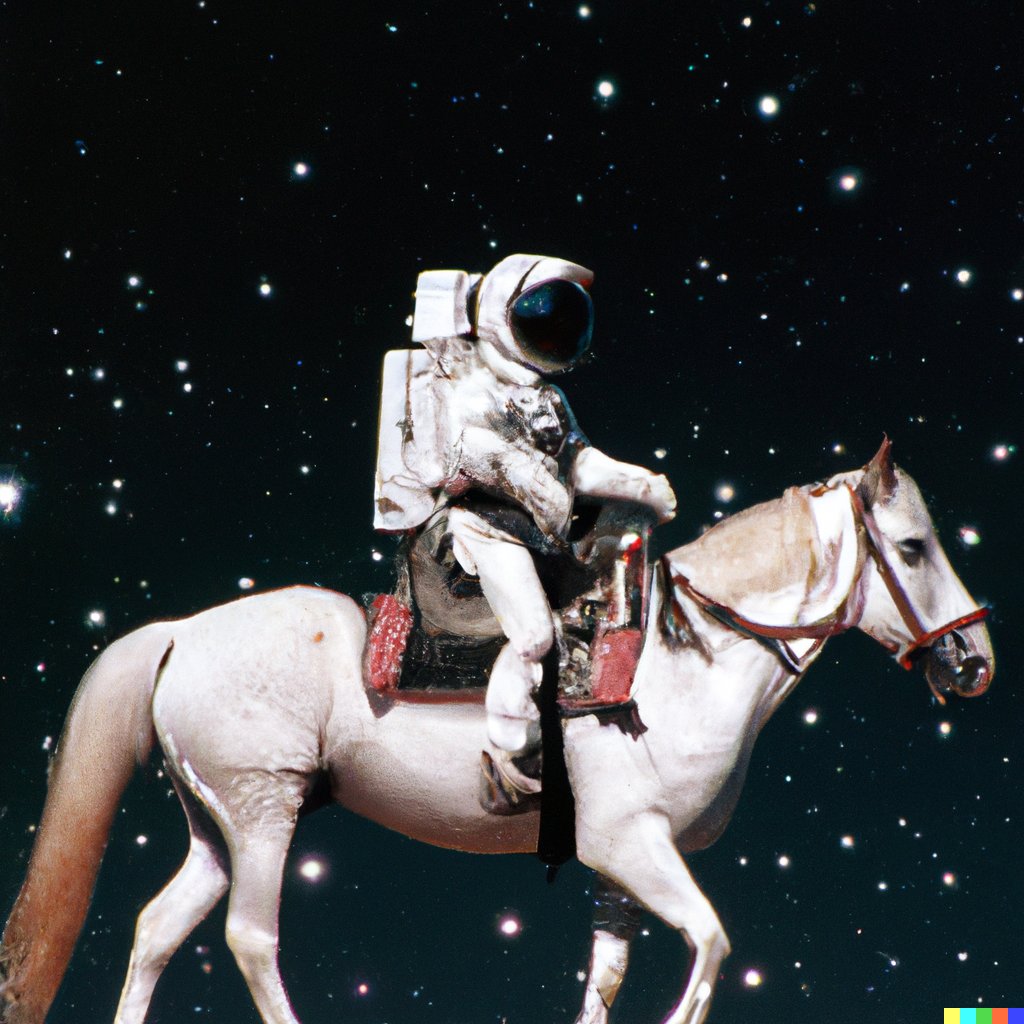

An image generated by the AI program DALL-E 2. Courtesy of OpenAI.

No matter which side of the tipping point we’re on, the march of A.I. image production is being met with more and more pushback. Getty Images, the sprawling subscription-only photography and illustration library relied on by thousands of publications, announced a ban on content made with text-to-image generators only days before DALL-E became publicly accessible. A handful of dedicated online art communities have recently blacklisted all content made with A.I. assistance. The same is true for the Reddit forum on Frank Herbert’s sci-fi classic Dune. Critics have lashed out at even smaller targets, too, ranging from the jury for an art contest at the Colorado state fair to a lone tech-and-culture writer at The Atlantic.

The issues motivating the actions above are varied, real, and complex. How do you protect the copyright of image-makers whose works could be (and probably are) scraped as reference points by hungry algorithms whose parameters are proprietary? Setting aside the legal ramifications, what should be the ethical boundaries in this nascent relationship between art and tech? Where do the outputs from text-to-image generators land on the spectrum between “low-effort” content (as the Dune subredditors called it in their scarlet-lettering of A.I.-assisted imagery) and legitimate creative achievements? Who gets to decide?

The answers are still going to be contested years from now. What I want to do in this column is to try to chalk the lines on the playing field with the help of two artists who have been wrestling with the questions long before DALL-E and company made landfall on the public consciousness, primarily by investigating the space between two sets of opposing views.

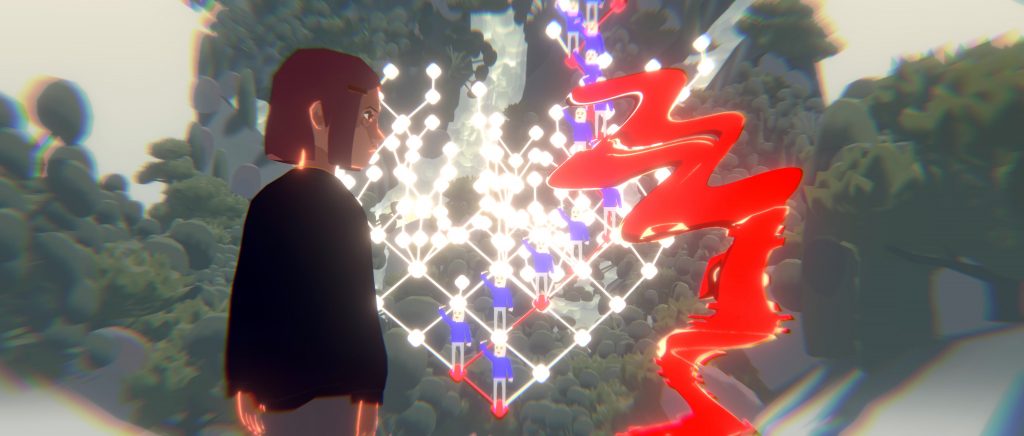

Ian Cheng, BOB (Bag Of Beliefs) (2018-2019), detail. Courtesy of the artist.

While there are differences between the various bans and backlashes mentioned above, one crucial shared trait is that they all concern images presented as final artworks even though the human users basically just followed the manufacturer’s instructions. In other words, they typed in a description of the visuals they wanted the software to produce for them, then submitted the output to a contest, online forum, or database with no further intervention.

Where I tend to part ways with some other critics of this process is how to classify its endpoint. To me, it’s not fraud, larceny, or heresy. It’s just research and development—a conclusion I came to partly thanks to Ian Cheng.

Cheng has become arguably the art establishment’s best-known, most-acclaimed creator of A.I.-driven artwork. In particular, his specialty is agent-based models, in which algorithms learn how to adapt their behavior in response to an unstructured environment rather than a single programmer-determined goal. Although this is a different branch of A.I. from text-to-image generators, his experience in the former gives him a clear perspective on the value of the latter.

“In terms of process, I can see A.I.-assisted image generation being like a concept artist sitting next to me to instantly flesh out half-formed ideas, or A.I.-assisted text generation eventually being a cheaper, faster kind of writer’s room. I can see it suggesting details of a world that hadn’t been worked out yet, or parts of a world that just require a good-enough pass,” Cheng said.

In other words, DALL-E and company excel as a waypoint on a longer creative process. But if the waypoint is presented as an endpoint, with the user either literally or symbolically building nothing else on top of what the algorithm produced from their prompt, the merits need to be evaluated differently.

This also means the greatest promise of A.I.-based image generators isn’t that they will create incredible finalized artwork; it’s that they will create efficiencies that can help level the playing field between blue-chip artists’ studios and up-and-coming talent. Cheng put it this way:

“In the end, I think all of these tools will enable an individual artist to do much more with less energy, time, resources, and personnel, in ways that begin to rival larger-scale productions. This sort of pressure on high-quality cultural production is a good thing. It means what’s truly interesting and of value to us as a culture gets further clarified.”

One key word in his answer above leads us to the next debate about A.I.-assisted image-making.

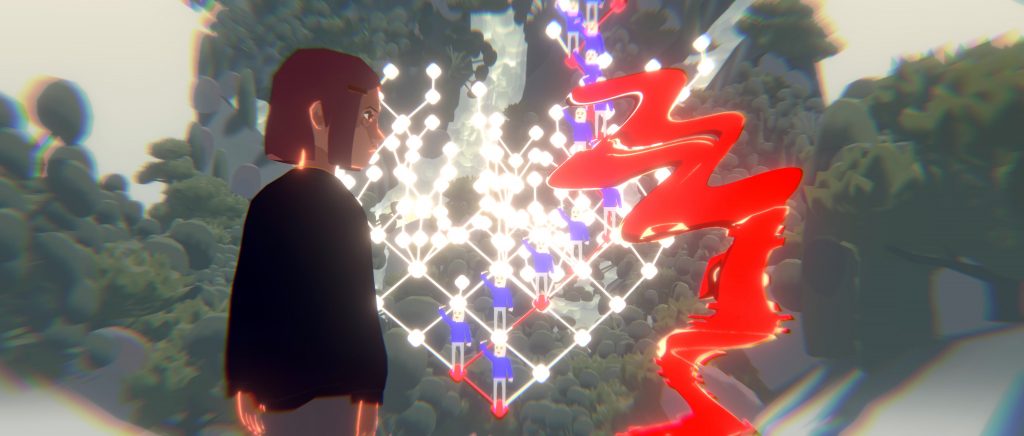

Jacky Connolly, still from Descent Into Hell (2022). Courtesy of the artist.

One of the most popular lines from both many artists who are enthusiastic about working with A.I. and the tech companies behind the technology itself has been that algorithms are “just a tool, like a paintbrush or camera.” I’ve been hearing, reading, and thinking about this framework for years. After all that time, I think it’s only accurate up to a certain point—and beyond that, it becomes grossly misleading.

When I asked Cheng about the “tool” label for A.I., he endorsed it as “useful… because it keeps the emphasis on the agency of the artist to use the tool, explore its affordances, imaginatively combine it with other tools, and update some parts of their existing processes.” In other words, a text-to-image generator or other A.I. is not a magic wand. It is an imperfect implement that can be used well or poorly depending on how thoroughly someone understands its strengths and weaknesses, and how laterally they can think about the way it fits into their practice.

To Cheng, this makes text-to-image generators “both exciting and, soon, mundane. In the end, AI-driven tools are another choice in the artist’s toolbox. Making art still requires imagination and nerve, both of which are moving targets relative to our culture, so the criteria for making good art remains the same.”

I agree with all of that. At the same time, Jacky Connolly, whose computer-generated video installation Descent Into Hell (2022) was one of the standouts of the 2022 Whitney Biennial (partly due to its eyebrow-raising use of an Emma Watson deepfake), pointed out a major complication to framing DALL-E and its rivals as 21st century equivalents to traditional artistic tools: they are products whose ultimate purpose goes far beyond the creation of images, and whose inner workings are still proprietary to everyone but the company that engineered them.

To her, a text-to-image generator is “an apparatus that someone else created towards their own ends.” Every prompt and subsequent refinement doubles as data used to further train the algorithm, as well as to augment the developer’s efforts to build even bigger, better products from the same underlying toolset. (In the case of DALL-E, the endgame is artificial general intelligence, the type of all-encompassing digital sentience familiar to sci-fi fans.)

When it comes to a text-to-image generator, then, “You’re not just playing with it. You’re playing against it, because it’s something that already has its own invisible logic,” Connolly said. “That’s where the paintbrush comparison falls apart.”

Installation view of “Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept,” including a detail of Jacky Connolly’s Descent Into Hell (2022) in the foreground and works by Jane Dickson (left) and Sable Elyse Smith (right) visible in the background. Photograph by Ron Amstutz.

Like Connolly, I’m not concerned about these implications in an alarmist or dystopian way. I just think that the veiled techno-capitalist realities of A.I. image generators clamp another handcuff on how artists can and should use them. Case in point, Connolly mentioned that the imagery being made with current text-based generators already feels “less transgressive” than it did a few months ago, when the cruder DALL-E Mini went viral thanks to early users shitposting the most outrageous prompts they could conjure. (Personally, the one burned into my memory forever is “9/11 gender reveal,” an image of the Twin Towers pouring baby blue and pink smoke out of the catastrophic gashes in their upper floors.)

I suspect A.I.-assisted visual production will get even tamer as time goes on. The threats of online scandals, disinformation warfare, and lawsuits over copyright and intellectual-property violations should push the companies that crafted the software to safeguard themselves and their users by becoming more and more restrictive about the types of images their resources can be used to produce. The parameters of most or all of these algorithms are also nearly sure to keep being tweaked in other ways undetectable to outsiders, just as social-media algorithms are, meaning users may never quite know how to harness or hack the A.I. in compelling ways.

This is one major reason Connolly has spent much of the past decade using mods of popular video games like Grand Theft Auto V (for Descent Into Hell) and The Sims as the source material for her dread-laced C.G. narratives: the developers’ agenda is right there on the surface. “To make it your own, you know immediately what you’re up against,” she said. Not so with text-to-image generators, whose status as tightly guarded, ever-changing black boxes of A.I. make them exceedingly difficult, if not impossible, for an artist to subvert on a meaningful level.

If all of this seems nuanced and maybe even a little uncomfortable, well, that’s because it is—and it’s only going to become more so once the number of A.I.-assisted images definitively overtakes the number of A.I.-free images (again, if it hasn’t already). Even if I’m misreading the specifics of how art, media, and life will change as a result, I’ll bet my professional reputation that the starting point of any worthy analysis will be to recognize the tipping point as momentous and loaded but not necessarily apocalyptic.

There is plenty of friction between those three adjectives, but at least the friction created from holding them all in one’s head at the same time is offset by their potential to spark some progressive thinking in what is rapidly becoming one of the most consequential avenues in 21st century image-making. Anyone unable or unwilling to handle the discomfort is doomed to add nothing but knee-jerk rage or pat boosterism to the discourse. My advice: make your choice now, because the technology is going to continue racing ahead either way.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: you can’t push the boundaries if you’re not even sure where they are.