The Gray Market

DALL-E’s Astonishing Images Mask That Art Is Just Another Pawn in Silicon Valley’s Endgame (and Other Insights)

Our columnist unravels how DALL-E and other A.I.-driven content generators fit into Big Tech’s grand business plan.

Our columnist unravels how DALL-E and other A.I.-driven content generators fit into Big Tech’s grand business plan.

Tim Schneider

Every Wednesday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, looking up from the latest shiny novelty…

In a competition for the year’s most significant art-and-tech development, the colossal upgrades in A.I.-powered text-to-image generators like DALL-E belong somewhere on the medal stand. Even while still in beta, these robust softwares have already provoked intense debate about issues vital to the future of the art industry, including how the creation, dissemination, and valuation of images will change once high-quality algorithmic production is available to the public at large.

But two of the most important questions about DALL-E and its competitors have so far managed to slink by without attracting the scrutiny they deserve: Why are the tech behemoths developing these image-making tools in the first place? And what does it say about how Silicon Valley views art and culture? The answers clarify that visual art is yet again being used as a stepping stone in a campaign for a much larger, more lucrative win.

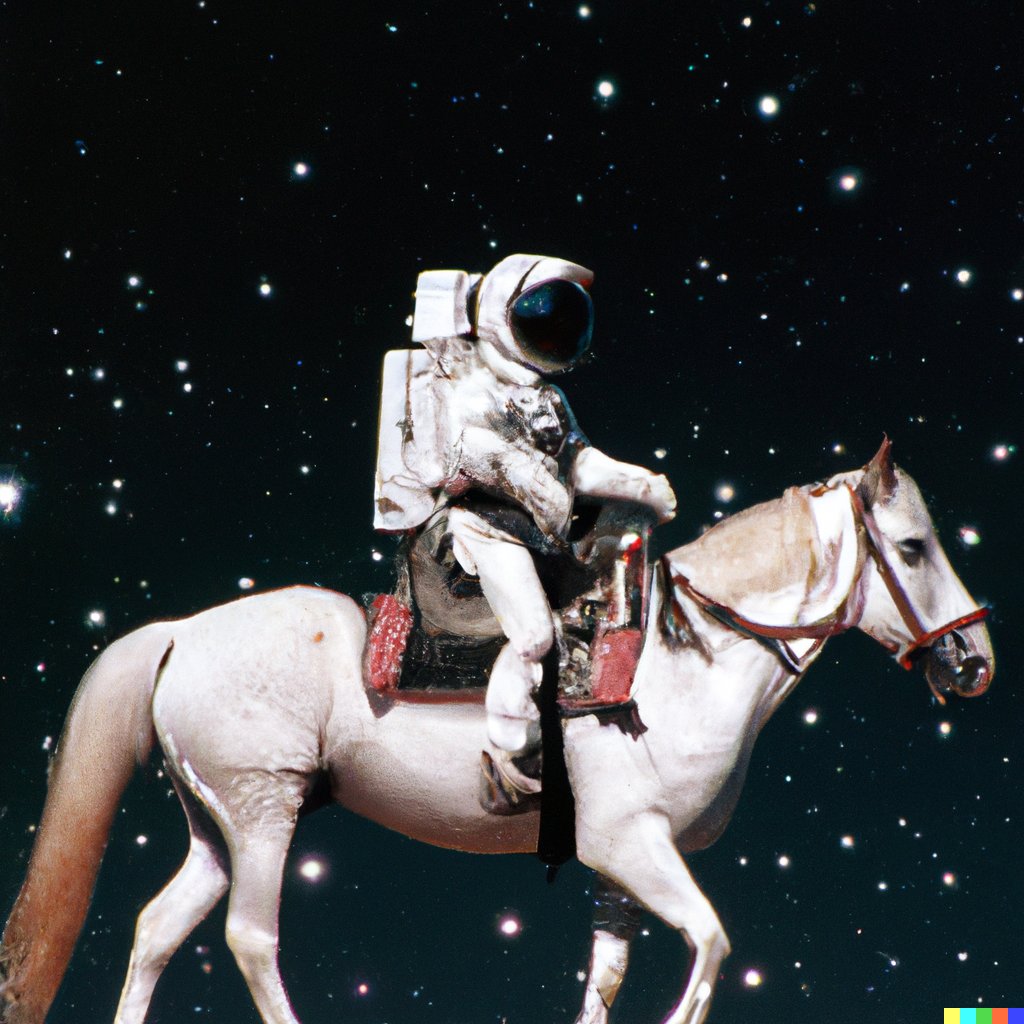

Let’s back up. For the uninitiated, the basic premise of text-to-image generators is right there in the name. Using A.I. trained on hundreds of millions of images, these softwares process users’ short descriptive prompts into surprisingly on-point visuals of almost any conceivable subject matter in almost any conceivable stylization. More remarkably, the results appear in a matter of seconds and can be continuously refined with minimal effort, leading to both an endless parade of absurd memes and heady new aesthetic possibilities such as the Recombinant Art movement.

For example, users could just ask for a plain old “astronaut riding a horse on the moon” and see what the algorithm produces, or they could try to try to narrow the output by applying much more detail—say, “knees-up close-up of astronaut from the 1969 Apollo mission riding a Palomino on the dark side of the moon, photographed by Richard Avedon.” (If this sounds daunting, don’t worry, there is already at least one free online “prompt book” to walk readers through the generative possibilities of DALL-E’s second iteration. More are undoubtedly on the way.)

Until recently, every prominent text-to-image generator has only been available to a select group of beta testers. The list included DALL-E, Google’s Imagen, Meta A.I. (formerly Facebook)’s Make-a-Scene, and independently financed Midjourney. DALL-E has risen to the forefront of the conversation largely because the startup behind it, OpenAI, has been more willing to share its progress than its competitors.

Still, the algorithms fueling the image generators are mostly under wraps, partly for commercial reasons (more on this in a bit), and partly for the good of the commonwealth. In the wrong hands, existing text-to-image generators are now powerful enough to make deepfakes and large-scale disinformation a genuine threat. OpenAI has already installed some guardrails including watermarking all outputs and blacklisting the use of political, violent, or pornographic prompts. (Midjourney has similar preventive measures in place as of my writing.)

These are all valuable, necessary steps toward good governance in a high-stakes arena. Holding off a wider release buys time for the producers of text-to-image generators to work on even deeper problems inherent in the softwares, such as counteracting the biases embedded in so much of the data used to train A.I. models.

However, the latest generation of DALL-E (technically DALL-E 2) and text-to-image generators more broadly present other dilemmas—specifically, dilemmas that arise from what the software already does so well, how it achieves its results, and where the tech is headed long-term. All of these elements should give artists, art professionals, and everyday people pause about the future of imagery in an A.I.-driven world.

OpenAI cofounder Sam Altman at the Sun Valley Conference in 2018. (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

As a professional skeptic, I believe that the first questions that need to be asked about any new technology are the same as the first questions that need to be asked about any new venture: Who’s running it, and where does their money come from?

In the case of DALL-E, the answers are revealing. OpenAI is a private, Bay Area company directed by Sam Altman, a 37-year-old Silicon Valley entrepreneur and angel investor. Altman formerly served as partner at, and later president of, Y Combinator, the most storied startup accelerator in 21st-century tech. By August 2015, Y Combinator alumni had reached a collective valuation of almost $65 billion; graduates of the program included the likes of Airbnb, Dropbox, and Stripe. In addition to early stakes acquired in these companies in exchange for Y Combinator’s guidance, Altman has also invested millions of dollars more through his angel fund, leaving him with a net worth estimated to be north of $200 million by various (admittedly dubious) aggregators of wealth.

In 2015, Altman cofounded OpenAI with one Elon Musk. The duo originally incorporated the venture as a nonprofit—a decision that its name still seems to conjure today. But after Musk left in 2018 to focus on A.I. inside his primary moneymaker, Tesla, Altman converted OpenAI to a for-profit company “so it could more aggressively pursue financing,” Cade Metz at the New York Times wrote in 2019. The move paid off in a colossal way. That year, Microsoft invested $1 billion in the project as part of a long-term deal that will eventually make the computing giant OpenAI’s exclusive hardware provider.

The two companies’ aspirations are much loftier than either DALL-E or image-making more broadly. The ultimate aim is to create artificial general intelligence (AGI). I’ve previously defined AGI as the evolutionary endpoint of A.I. popularized in science fiction: a thinking (and perhaps even feeling) machine that can establish and pursue its own goals, with the entire corpus of digitized human knowledge at its command.

AGI is a kind of technological Holy Grail. Several researchers and entrepreneurs on Altman’s level believe it’s a pipe dream; others believe it is an achievable goal that could improve (or destroy) every aspect of life on earth. No surprise, then, AGI is also being pursued separately by an elite group of other labs lavishly funded by the richest, most powerful names in tech, led by Alphabet (Google’s parent company), Amazon, and (it is widely believed) Apple, among others.

Where does text-to-image generation fit into this grand campaign? As a hoped-for path to AGI, OpenAI has essentially split human cognition into its component parts, then poured resources into deciphering each one through an individual project with shared fundamentals. Another OpenAI endeavor, GPT-3, can now quickly conjure pages and pages of spookily proficient text using prompts similar to the ones DALL-E uses to produce visuals—though not without some troubling failures, as journalist Steven Johnson recently wrote:

GPT-3 has been trained to write Hollywood scripts and compose nonfiction in the style of Gay Talese’s New Journalism classic ‘‘Frank Sinatra Has a Cold.’’ You can employ GPT-3 as a simulated dungeon master, conducting elaborate text-based adventures through worlds that are invented on the fly by the neural net. Others have fed the software prompts that generate patently offensive or delusional responses, showcasing the limitations of the model and its potential for harm if adopted widely in its current state.

So, while GPT-3 attempts to dissect natural language, DALL-E works to codify how our brains relate natural language to images. An earlier project taught an A.I. how to become the world’s greatest player of the widely loved esports game Dota 2. All of these and more are milestones on the path to OpenAI’s final destination: “If they can gather enough data to describe everything humans deal with on a daily basis—and if they have enough computing power to analyze all that data—they believe they can rebuild human intelligence,” Metz writes.

Over here in the art industry, it’s worth asking what’s being sacrificed along the way, and whether the rest of us are getting enough out of the exchange to justify our role in it.

Unlimited Dream Co., Stained Glass (2022). Courtesy of Unlimited Dream Co.

Intermediary products are likely to make OpenAI profitable long before it cracks the code of AGI (if it ever does). The firm appears to have launched a metered subscription model to license out DALL-E as-is to all interested parties. It is also charging other companies a fee to access its APIs, the underlying tools that would allow engineers to build on top of existing softwares like GPT-3 and DALL-E.

If you’re wondering what that would mean, Metz wrote in 2019 that software like GPT-3 “could feed everything from digital assistants like Alexa and Google Home to software that automatically analyzes documents inside law firms, hospitals, and other businesses.” In this vein, I could see the DALL-E API being sold to individual artists, architecture and design firms, and video-game, film, and animation studios, who could all iterate even more customized software. Other A.I. models are already being leveraged to try to fight forgeries in the art market, and the current DALL-E toolbox might be able to further that goal considerably, too. More—and potentially increasingly lucrative—use cases are bound to manifest as the software continues to improve.

Who does OpenAI owe for all this upside, though? It’s undeniable that the startup has done groundbreaking work to create DALL-E and GPT-3. But these advanced A.I. models would be useless without a vast, rich set of training data. (In fact, it would be impossible to build them in the first place.) The key point is that, here, the training data is a collective resource, namely everything the world has ever put online. Johnson argued on a recent podcast that the situation creates an ownership paradox:

“These companies are coming in and sweeping all that [data] up and saying, ‘Well, great, we can build incredible products on top of that,’ like it’s just some natural resource that’s been sitting in the ground somewhere. But in fact, it was something that was created by human beings all around the world. We need to be way more imaginative in thinking about who created that value if, in fact, it does become as valuable as I suspect it will be.”

This imbalance (which already exploited us all in the social-media era) creates two troubles in the specific case of DALL-E and visual art. First, to paraphrase a bit of my colleague Ben Davis’s new book, Art in the After-culture, A.I.-driven image generators reduce art history to a collection of visual patterns stripped of all context and meaning. In the most cynical case, the unique style of Vincent van Gogh or Frida Kahlo or any other canonical giant essentially becomes a photo filter for memes to help drive revenue for multibillion-dollar corporations.

The public loses out, too. As arts writer and professor Charlotte Kent recently wrote about generative art, “The increase in no-code tools allows more people to be creative, but it also forecloses an understanding of what we are using and how those systems are using us.” In other words, A.I.-powered image generators like DALL-E are so intuitive that most of us will never have to think about either their technological or economic workings, including how every prompt we run doubles as unpaid labor for the Silicon Valley elite.

I don’t mean to imply that OpenAI is malevolent. Johnson, whose critical eye was informed by several days spent inside the company’s headquarters, said that he believes Altman and his team are earnestly trying to do the right thing, and he credited them for taking “the opposite of the ‘move fast and break things’” approach popularized by Mark Zuckerberg. All of this sounds plausible, even likely, based on what I know of the people and issues involved.

Still, he couldn’t overlook an inherent disconnect in its business model: a company trying to build A.I. software to improve the quality of life for all of humankind is still being governed by a handful of entrepreneurs, engineers, and financiers in San Francisco. Barring a major change, this insularity is likely to have far-reaching impacts on art, commerce, and wellbeing that no one in OpenAI’s headquarters can fully anticipate. Unless we in the cultural field understand the stakes, there’s little chance that most of us will be able to do more than hang on for the ride, wherever it takes us.

[Artnet News | The New York Times]

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: even when there’s no one else in the room, you’re always being evaluated.