The Gray Market

The Virality of That Broken Jeff Koons Sculpture Says a Lot About Art’s Place in the Mainstream

Our columnist picks up the pieces of why a smashed Jeff Koons edition worth $42,000 became one of the biggest stories anywhere.

Our columnist picks up the pieces of why a smashed Jeff Koons edition worth $42,000 became one of the biggest stories anywhere.

Tim Schneider

Every week, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, on learning from mistakes…

Whether in the art business, the media business, or life in general in 2023, sometimes the best tool to unearth something extremely important is, in fact, something extremely dumb. A case in point just transpired less than two weeks before this column went live, in the form of a wayward visitor accidentally shattering a $42,000 Jeff Koons “Balloon Dog” sculpture during the VIP opening of the Art Wynwood fair in Miami.

I’ll be floored if almost everyone reading this sentence right now hasn’t already digested at least a social-media summary of the mishap given how widely it was covered. While the story had almost no significance inside the art trade, its extreme virality elsewhere is a sobering reminder of contemporary art’s chief value to the larger media ecosystem of this era.

To review, here are the basics of the story: On Thursday, February 16, an unidentified woman bumped into a pedestal displaying an edition of Koons’s Balloon Dog (Blue) in the booth of Bel-Air Fine Art. The porcelain piece tumbled to the floor and smashed beyond repair. A dense crowd quickly converged on the debris. Some spectators tried to figure out what happened; some gawked at the chaos; and not surprisingly, others whipped out their phones and started recording content for their social platform of choice.

Shattered into pieces: Jeff Koons’s Balloon Dog got knocked over and broken at Art Wynwood on February 16, 2023. Photo courtesy of Cédric Boero, district manager of Bel-Air Fine Art.

One of those amateur paparazzi was artist and collector Stephen Gamson, whose activity in the accident’s aftermath is an absolute clinic on how to intercept a beam of pop-cultural attention initially aimed elsewhere. Gamson told the Miami Herald (and other media outlets) that he saw the woman knock over the sculpture, and his Instagram post on the episode contains multiple videos of the debris and its unceremonious cleanup by event staff wielding dustpans and brooms. To get to the videos, however, you first need to swipe through two photos of Gamson shoulder-to-shoulder with Koons and an image of the work in pristine condition (seemingly cribbed from the website of French ceramics maker Bernardaud, with whom Koons created this particular “Balloon Dog” edition).

The post also comes equipped with a lengthy caption in which Gamson calls the accident “one of the most crazy things I’ve ever seen,” then immediately pivots to letting the world know that he “tried to purchase the broken sculpture” because it “has a really cool story.” (In fact, you can actually hear him start to make an offer to a Bel-Air Fine Art staffer near the end of one of his videos, saying, “If you want to sell the tail…”)

Gamson wasn’t alone in reaching for his wallet, according to Bel-Air Fine Art district manager Cédric Boero. He told my colleague Vivienne Chow that multiple buyers reached out to the gallery after the crash to try to buy the balloon dog’s remains. But Boero also said at the time that the shards had been packed up in a box so the gallery could process an insurance claim.

It’s no surprise that Artnet News, our art-media peers, and our competitors in the expanded field of cultural coverage (think: Hypebeast, Complex, and others at the nexus of style and collectibles) all assigned writers to churn out quick recaps of the fragmented mini-Koons. But what perked up my eyebrows was how many other publications chased down the story, too.

The crowd included the widest-circulation legacy newspapers in the U.S. (the New York Times, Washington Post, and Los Angeles Times), major national T.V. and radio outlets (CBS News, CNN, Fox Business, NPR), acclaimed news organizations abroad (BBC, The Guardian), publications focused on wealth and general business (Business Insider, Financial Times, Robb Report), ostensibly regional newspapers (the New York Post, Palm Beach Post, and Seattle Times), a slew of local TV stations both stateside and overseas, and—somehow, weirdest of all—even Smithsonian Magazine, the primary media arm of the most hallowed consortium of museums in the U.S.

To his credit, Gamson was right. The end of his Instagram caption reads, “You will see this all over the news in 30 countries and in many different languages. It’s going global.” The question is: Why? And more importantly for this column’s purposes, why does it matter for the art business?

Visitors streaming into Frieze Los Angeles, 2023. Photo: Casey Kelbaugh. Courtesy of Casey Kelbaugh and Frieze.

The reach of the shattered Koons story is all the more remarkable to me because of another U.S. art fair that debuted to VIPs on Thursday, February 16: Frieze Los Angeles.

There is no credible argument to be made that Art Wynwood is a bigger deal more deserving of cultural media coverage (however superficial it might be) than Frieze L.A. The latter fair drew dozens of the highest-powered galleries, artists, collectors, curators, and more (including several mainstream celebs) to do millions of dollars’ worth of business in the undisputed glamor destination of the west coast.

And yet, I would bet my two front teeth that the number of people worldwide who read, saw, or listened to news about the destruction of the $42,000 “Balloon Dog” sculpture in Florida eclipsed the number of people who read, saw, or listened to news of any kind about Frieze L.A. in the days following their concurrent VIP openings. Based on search results, I doubt the competition would even be particularly close.

Explaining the discrepancy is no simple task.

Part of it needs to be done through the lens of cultural criticism. Fortunately, my colleague Ben Davis did Olympian work on that front just days before things went bust at Art Wynwood, in an essay that dissected the curiosity of a New York Times feature arguing that viral footage of a brawl between customers and workers in a Waffle House franchise in Austin, Texas bore a legitimate aesthetic kinship with the paintings in “Edward Hopper’s New York,” the acclaimed show on view at the Whitney through March 5.

The scope of Davis’s analysis included both the original Times piece and a spate of reaction coverage from other outlets. The former, he wrote, “has the hallmarks of a rushed ‘smart take,’ born of the imperative to hop on the traffic generated by a viral trend but also somehow meant to justify it to Times readers by giving it a gloss of social commentary and artistic legitimacy.” But his larger point was about the main force shaping media discourse as a totality in 2023:

At this point, it’s not just the digital image but viral culture that is the dominant force. The conversation around something looms larger than the thing itself. The image is a vehicle for takes and counter-takes and riffs as it circulates, and [gets] drained of its specificity in the process of being meme-ified. That’s how you arrive at seeing a workplace assault as first of all some kind of spectacle to riff on, and only secondarily as an actual workplace assault.

This same phenomenon also applies to events, not just images, and it helped drive the story of the shattered Koons sculpture far and wide. A thing happened; people witnessed it, recorded it, and (in at least a few cases) instantly tried to leverage it into something self-serving. Media organizations of many stripes did the same, inflecting their coverage in different ways to transform a banal accident into news, or grist for the opinion mill, or whatever best suited their format, mandate, and audience. (Davis acknowledged in his critique of the Waffle House/Hopper essay that he was joining in the same exercise, and now I’m guilty, too.)

Still, I think this dynamic was only one piston in the engine that drove the broken Koons story so near to inescapability. Three other traits also made it perhaps the perfect viral art story of 2023, and those other traits say an awful lot about contemporary art’s standing in the eyes of the general public.

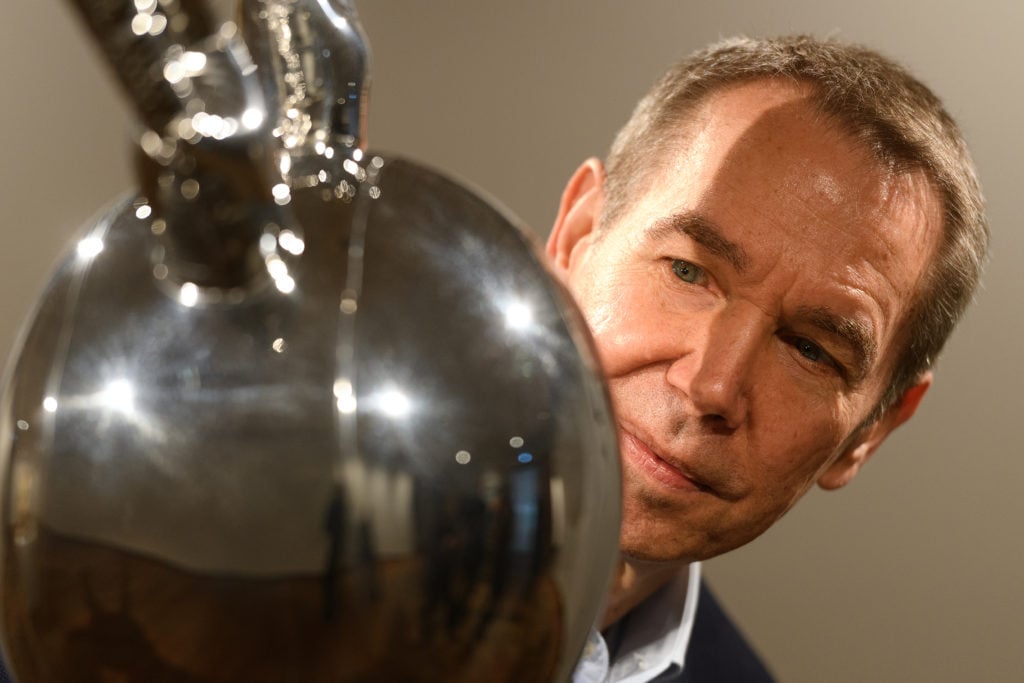

NEW YORK, NY – NOVEMBER 15: Jeff Koons and Alicia Kunkel attend Balloon Dog Blue 2021 By Jeff Koons & Bernardaud at Bernardaud Flagship Store on November 15, 2021 in New York City. (Photo by Jared Siskin/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images)

After spending more than five years inside a major online publication, I can tell you this much: if you’re trying to amplify an art story’s reach, jam a big, fat price in the headline, especially if it comes from an artist successful enough to have some mainstream cachet.

This rule has been backed up again and again by Artnet News’s data on how many readers click-through to stories and how much time they spend once they’re inside. So if you’ve ever been frustrated by how often art-media verticals publish stories about sales or valuations rather than exhibitions or projects, the main reason is simple: more people usually read them.

The broken Koons sculpture is an interesting case study in this rule, though. You don’t need me to tell you that $42,000 isn’t all that much money in the grand scheme of the 21st century art market. After all, this wasn’t a monumental Koons sculpture, like his Balloon Dog (Orange) (1994–2000), which sold for $58.4 million at Christie’s New York in 2013. It was a domestically-scaled sculptural multiple produced in an edition of 799.

But $42,000 is still a significant stack of bills to the average consumer of media. As one reference point, the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that the median annual wage of full-time workers in the U.S. in the fourth quarter of 2022 was $56,420. So, for half the American population with a full-time job, the woman who knocked over the balloon dog vaporized, at minimum, 75 percent of their gross earnings last year. In that sense, it’s still a lot! This tragicomic loss leads us to the second point…

Sotheby’s employees view Love is in the Bin by British artist Banksy during a media preview at Sotheby’s auction house on October 12, 2018 in London, United Kingdom.(Photo by Jack Taylor/Getty Images)

Bénédicte Caluch, described as an art advisor with Bel-Air Fine Art, framed the breakage of the sculpture as follows to the Miami Herald: “It was an event! […] Everybody came to see what happened. It was like when Banksy’s artwork was shredded.” I’d bet that this analogue was also on the minds of Gamson and the unnamed others allegedly interested in buying up the fragments because of the part they played in, to bring back the words in his Instagram caption, “a really cool story.”

With all due respect to Caluch and company, though, this was pretty much nothing like when Banksy’s artwork was shredded. If you need a memory jog, the episode in question was the October 2018 sale of Banksy’s Girl With Balloon (2006) at a Sotheby’s contemporary evening sale in London. As soon as the final gavel fell at £1 million ($1.4 million), someone in league with the artist activated a remote-operated shredding mechanism secreted away in the work’s frame. The device began slicing the painting into ribbons until a malfunction stopped the process midway. The moment was captured on the auction house’s livestream, went viral, and led to Banksy rechristening the half-shredded scraps as a new work, titled Love Is in the Bin, which went on to sell for £18.6 million ($25.4 million) at another Sotheby’s evening auction in October 2021.

What happened at Art Wynwood was infinitely more mundane. Instead of a unique multimillion-dollar artwork being ingeniously sabotaged by one of contemporary art’s premier provocateurs on the live broadcast of an A-list art-market event, a run-of-the-mill accident involving a hapless bystander destroyed a modestly priced sculptural edition at a minor art fair in Florida. I won’t criticize the sound bite from Caluch, who was pretty clearly just trying to make the best of an unfortunate situation. That said, anyone else trying to equate the mishap to Banksy’s shredding, or arguing that the chain of events leading to it was somehow memorable or noteworthy, is either missing the point by light years, or hoping to run some kind of greater-fool scam on the rest of us. But hey, the comp makes for great copy, no matter the audience, because…

Jeff Koons looks at his Rabbit. Photo by Leon Neal/Getty Images.

If you think Jeff Koons is a hack, you can laugh about his work being displayed and destroyed at an event outside the upper tier of the market. If you’re a seasoned professional inside the art establishment, you can roll your eyes at the people trying to portray an embarrassing accident as a creative evolution and a financial value-add. If you’re an everyday person with little to no interest in the arts, you can do all of the above, while also taking shots at the original artwork (silly!), the original price (absurd!), and the precarious way it was installed (careless!). That goes double for the people who actively hate contemporary art, partly for its status as an avatar of the coastal elites who take it so seriously. To me, this is one of the reasons that the vandalism and obliteration of art has become an increasingly prevalent theme in pop culture and political discourse lately.

Basically, the story is a schadenfreude carnival just waiting to be exploited. Even though not every media outlet treated it in the crassest manner imaginable, the feeding frenzy still makes me feel gross.

But my queasiness doesn’t come from the fact that so many editors and publications outside the arts responded to these incentives; it comes from the fact that the incentives were there in the first place. In a flattened media ecology, where legacy mastheads are as responsive to clickbait as cut-rate online news aggregators, and where every bystander thinks about how their social-media content could lasso the spotlight away from the events they witnessed, the masses will continue to associate contemporary art mainly with astronomical prices, viral stunts, or behavior that deserves to be mocked—if not all three. And that’s the type of lesson taught best by the dumbest possible events.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: when you gaze outside the art world, the outside of the art world gazes also into you.