Market

The Gray Market: Why Museums Can’t Compete With Private Collectors (and Other Insights)

This week, our columnist explores who can actually afford to buy masterpieces, the market of Josef Albers, and Snapchat’s collaboration with Jeff Koons.

This week, our columnist explores who can actually afford to buy masterpieces, the market of Josef Albers, and Snapchat’s collaboration with Jeff Koons.

Tim Schneider

Every Monday morning, artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, looking over developments in the fair sector, the auction sector, and the digital frontier…

FALSE EQUIVALENCE: Although I always advise caution about these reports, sales at this year’s freshly entombed Frieze and Frieze Masters were allegedly strong from the jump. Numerous exhibitors were eager to broadcast their results (or at least, pretend to) on VIP preview night. But rather than resurrect the issue of dubious honesty from self-interested actors in a consequence-free environment, I want to focus on a different dimension of the sales process this time: specifically, the growing imbalance between two types of buyers who used to be evenly matched.

In his dual-vernissage roundup, Nate Freeman talked with David Leiber, a director at David Zwirner, about his booth’s inclusion of the third and final available edition of Dan Flavin’s the diagonal of May 25, 1963 (to Constantin Brancusi). While Leiber stayed mum about the work’s actual price tag, he described its order of magnitude enough for Freeman to write “that it was in a range appropriate for an institution or a serious collector of Minimalist work.”

Of course, this is time-honored dealer code for “really f***ing expensive”—usually in the high six figures at least, if not seven. The caveat, however, is that evidence increasingly suggests that even major museums no longer have the resources to compete with major private collectors at the uppermost reaches of the price stratosphere.

Consider this: In fiscal year 2016—the most recent we have access to—MoMA spent just over $40.6 million on acquisitions. In contrast, recently minted Japanese mega-collector Yusaku Maezawa has already bought nearly three times that much art by value in 2017, through his publicized purchases of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Untitled ($110.5 million in May), Jenny Holzer’s Page 6 (an undisclosed amount in August), and Antony Gormley’s A Case for an Angel I ($6.93 million this week). And of course, those knee-buckling numbers only represent a few notable auction results. They don’t include whatever cash Maezawa has rained on the private market in the past nine-plus months, let alone what he may spend in the remaining quarter.

The point? More and more, suggesting budget equivalence between an institution and a “serious collector” is like suggesting that building a campfire produces as much heat as torching a lumberyard.

Admittedly, this isn’t an entirely fair comparison on my part. Zwirner represents the Flavin estate, meaning the diagonal is probably being offered on the primary market. Remember, secondary-market prices generally tower over primary-market prices like a domineering parent’s expectations over a dreamy-eyed young slacker. In that sense, the respective buying power of major institutions versus major collectors hovers somewhat closer together in this particular case than in the aggregate.

Still, when it comes to finances, it isn’t just that institutions and private buyers increasingly occupy different ballparks, or even different leagues. More and more, they’re verging on playing altogether different sports. And while galleries and dealers can still send useful signals to the art market by equating the two, there are definite limits to how far we should trust the comparison today. [ARTnews]

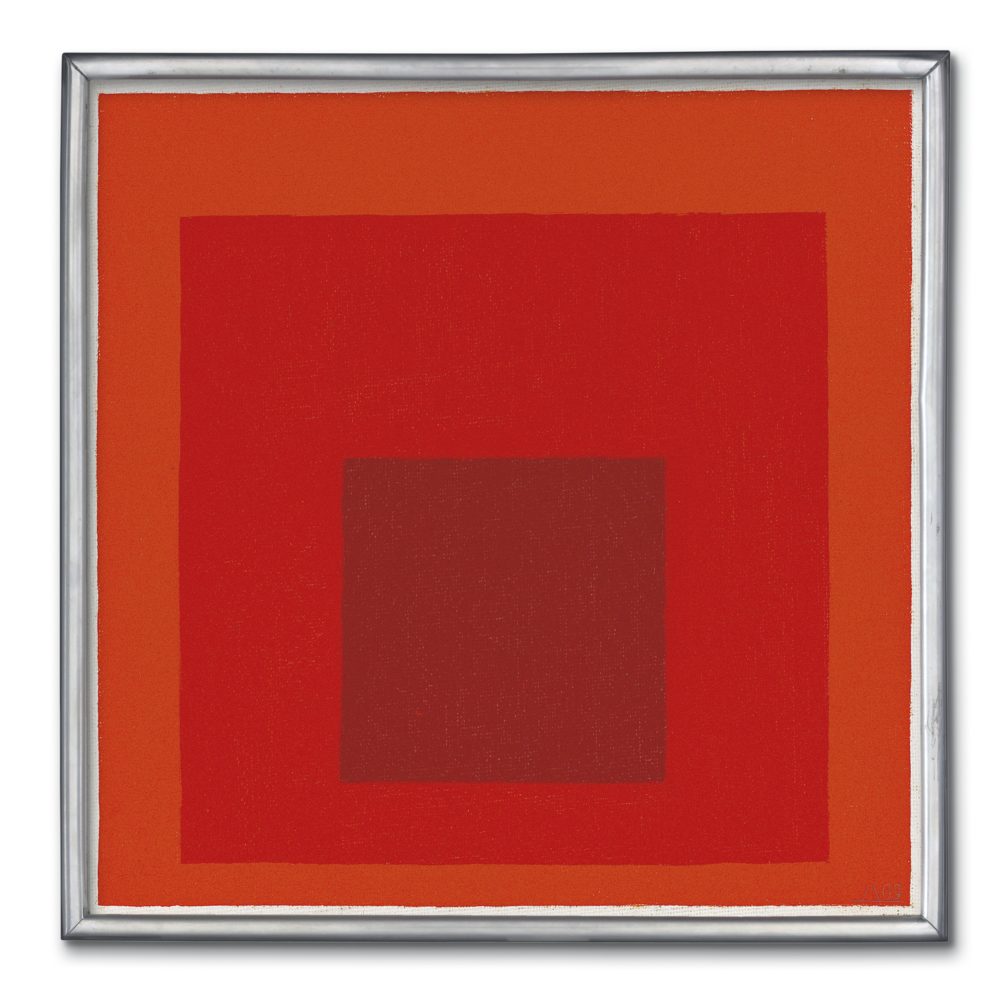

Josef Albers (1888-1976), Study for Homage to the Square: Containt. Courtesy of Christie’s.

SAME AS IT EVER WAS: On Thursday, James Tarmy launched into a deep dive on the evolving market for sultan of the square Josef Albers. And while he found significant growth in prices in recent years—particularly after Zwirner scooped up representation of the Albers estate with the ease of Jessica Chastain trawling an Irish bachelor party—he also identified one counterintuitive quirk that has so far limited its upside. In Tarmy’s words:

“The glaring market inefficiency in Albers works is chronology. For most artists… the year that the work was made is crucial to its value. Not Albers. A red painting that Albers made in 1954 carries the same price as a red painting he made in 1974.”

Instead, demand for Albers’s work tends to turn more on color and size, according to Tarmy. This dynamic contrasts sharply with that of, say, the Basquiat market, where Cristina Ruiz reports collectors are now hunting works from 1981-82 with the fervor of newly victorious hunger-strikers attacking a Thanksgiving dinner.

Tarmy rightly recognized—though perhaps underplayed, as Marion Maneker argued—that part of the problem for the Albers market is supply. Tarmy noted, “In total, there are more than 3,000 unique paintings by Albers in existence, according to his foundation; roughly two thirds of those,” according to a Zwirner rep, are from his Homage to the Square series—easily the most iconic and, therefore, most sought-after works by the artist.

But I would argue that another part of the issue is Albers’s consistency. While he made literally thousands of variations within this body of work, those variations are also the result of merely plugging different color combinations into the same format decade after decade. Based on Tarmy’s commentary and my own knowledge, you’d be hard pressed to find any significant formal developments or conceptual advances between the beginning and end of the series.

Although it’s rare to find a category where consistency is unfortunate, top prices for famed artists can be one. Serious collectors tend to gravitate toward sought-after artists’ early works precisely because they nod toward those artists’ mature styles without fully embodying them.

Why is this appealing? The answer is at least partially about self-image. Acquiring early works is one way for a competitive collector to big-time her peers on the buy side of the market, i.e. to “prove” that her taste level is more developed than theirs. What is connoisseurship (or at least, its illusion) other than an appreciation of qualities too nuanced or far-ahead for the mainstream to grasp?

At the apex of the art market, collectors are often willing to pay a premium to portray themselves as true experts. However, if an artist’s early and late works effectively look identical, it becomes impossible for this connoisseurship premium to emerge. (In this case, why would I pay extra for a 1954 Albers if it’s not going to demonstrate on sight that I’m a more advanced patron than you and your 1974 Albers?) And while that consistency won’t necessarily prevent an artist from generating blue-chip returns, at the upper echelon, it can help box in their prices as surely as Albers boxed in those 2,000 Homage canvases. [Bloomberg]

Jeff Koons talking about his new Snapchat collaboration. Screenshot courtesy of Moshe Isaacian via Snapchat.

SNAPPING AND TRAPPING: Finally this week, let’s turn to developments in the virtual art world.

On Tuesday, social-media mini-major Snapchat unveiled an augmented-reality collaboration with baron of banality Jeff Koons. By physically visiting Central Park, the Champ de Mars, or eight other global landmarks, Snap users can now find digital Koons sculptures ’embedded’ in the landscape via the app’s lenses, like a high-art version of Pokémon Go. Snap also packaged the announcement with an open call for digital artists, who the company claims in its application window that it “would love to work with.”

Personally, I don’t have many questions about the Koons side of this equation. The team-up is about as surprising to me as seeing a Kentucky congressman slamming country-club margaritas with a coal lobbyist.

But there’s a ton I’d like to know about what Snap is asking of, and offering to, the artists submitting to its open call. Since my request for comment went unanswered by my deadline, though, I’ll keep this contained to the macro issue: Why is Snap doing any of this?

The simple reality is that Snap is a business. Which means its brain trust will only launch a new initiative if they believe it can grow the business in one way or another. And that automatically means we should consider what an augmented-reality campaign can do for Snap’s bottom line.

When it comes to evaluating social-media companies, two of the metrics that analysts and investors tend to focus on are user base and “engagement,” or the amount of actual activity on the app. (50 million downloads mean nothing if no one ever opens the damn thing afterward.)

Both of these metrics factor into Wall Street’s opinions about what Snap is worth and whether it should be in anyone’s portfolio. Right now those opinions are tepid, and have been for months.

While Snap’s share price was up 1.17 percent on Friday, to $14.65, that figure “is still 13.6 percent lower than its IPO price of $17,” per Business Insider. In fact, the stock first plunged below that price back on July 10, roughly four months after going public, and hasn’t made it back above the waterline in the three months since.

Is augmented-reality (or just “AR”) art, whether by blue chippers like Koons or relative unknowns, likely to juice Snap’s user and engagement numbers in a huge way? I’m skeptical. While Axios has apparently reported that “more than a third of daily active [Snap] users interact with the AR features,” it’s important to keep in mind that those features are headlined by selfie filters that allow you to graft on a dog snout or puke rainbows. I suspect that those larks have a lot more draw to Snap’s user base than digital artwork.

Remember, despite its growing pop-cultural awareness, art is still a niche medium, not a mass medium. So if you want me to believe that the opportunity to see one of Koons’s giant inflatable bunnies posted up by the Eiffel Tower on an iPhone screen will power Snap to dramatic growth––and with it, profitability—your odds are about as strong as if you pitched me on introducing myself to my potential in-laws by gifting them a kilo of uncut heroin.

You know what investors and analysts love to see in social-media companies, though? Advertising revenue. Which is why every social-media app I’ve ever used has eventually moved to integrate ads directly into its stream of user-generated content. Innovation and communication are great, but they don’t pay the bills.

Granted, at this stage I don’t know what Snap can and can’t do with the AR works accepted through its open-call. But based on trends in tech, I’d advise digital artists to read the terms very carefully before agreeing to augment Snap’s reality any further. Expanding the audience for your work may not be worth the effort if it could also mean shilling someone else’s product down the line. [artnet News]

That’s all for this edition. Til next time, remember: Seeing isn’t necessarily believing.