Market

Rise of the Cyborg Art Dealers: How the Art Market Is Preparing to Adapt to a Hybrid Online-IRL Future

After 2020, here's what has changed, what will stay the same, and what's left to innovate in all corners of the art market.

After 2020, here's what has changed, what will stay the same, and what's left to innovate in all corners of the art market.

Eileen Kinsella

A version of this story first appeared in the spring 2021 Artnet Intelligence Report, which you can download in full for free here.

“Imagine a world where you could not fly around the globe anymore. How would you conduct business?”

That was the “thinking-out-of-the-box” assignment that a consultant gave Phillips executives at the auction house’s annual strategy meeting in January 2020. “We looked at each other, like, ‘What is he talking about?’” Cheyenne Westphal, the company’s chairman, recounted.

“Just imagine—there might be a volcano erupting,” the consultant told the assembled honchos, many of whom had traveled to New York for the occasion.

They were perplexed then. But what a difference 15 months makes. “I’m sitting here today,” Westphal said, “like, ‘Please ask me that question now.’”

The pandemic thrust the still-very-analog art world farther into the virtual realm than it had ever been—or expected to be. “We all learned so much as our business evolved—not just changed, but truly evolved,” Westphal said.

As with any kind of evolution, natural selection has been kinder to some segments of the industry than others. Art fairs have suffered dearly—and a rocky vaccine rollout pushed their return further into 2021. (Art Basel, widely expected to be the first major international fair of the post-lockdown era, announced in mid-January that it would postpone its Switzerland edition another two months, to September.)

On the flip side, the appraisal business is booming, in part because collectors with extra time on their hands got curious about the value of the assets they had hanging on their walls. Private sales have also proven resilient—perhaps not surprising given that the collective wealth of America’s 651 billionaires has jumped by $1 trillion since the start of the pandemic. Strong interest from millennials, who shored up vast amounts of disposable income amid lockdown, and robust activity from Asia are further fueling demand.

Some enterprising companies have also found unexpected revenue streams from behind their screens. In the pre-COVID era, New York-based art advisory and appraisal firm Winston Art Group held a handful of wine and whiskey tastings to, as managing director Elizabeth von Habsburg put it, “get our expertise and our brand out in front of people.”

The first few virtual experiments—in which an in-house expert selected and delivered wines to clients and then conducted tastings via Zoom—proved so popular that Winston ultimately made presentations to 120 different companies over the course of eight months.

Now, the firm is launching a wine app called “Vitis” that allows clients to analyze their collections, keep values up to date, and “provides advice about whether to hold, drink, or sell,” von Habsburg said.

Whether this all-remote moment has boosted or bruised businesses’ bottom line, it won’t last forever. And the art industry—like all industries—is starting to process what a hybrid virtual-IRL future might look like. Here is a breakdown of how four major segments of the sector will evolve. One thing is for certain: There is a whole lot more room to innovate in a post-lockdown world than there was before.

The pandemic has cemented the necessity of having a digital footprint—but dealers plan to be extremely judicious about where they put their dollars going forward.

Tom Burr, Bent Booze (2008) at The Upstairs, Bortolami Gallery, New York. Image courtesy the artist and Bortolami, New York. Photo: Kristian Laudrup.

What’s Changed: Dealers can no longer put off developing a digital strategy. “If you don’t have a cohesive hybrid, then you’re just not going to be relevant,” said Sean Green, co-founder of the art technology company Arternal.

That realization has resulted in the reallocation of resources. Tribeca dealer Stefania Bortolami admits that while her staff of 12 has produced some promotional video content, their capacity is limited. Now, she’s facing reality: “I might have to hire someone who takes care of digital.” There’s no time like the present, since, for once, art-fair costs are not eating into budgets.

Another Bonus: Artists no longer see a digital showcase as the equivalent of being stuffed into the storage room. Elena Soboleva, online sales director at David Zwirner, said artists have “started coming to us and actively driving the ideas and exhibitions in a way that was not happening before.” The artist Josh Smith, for example, conceived an open-air show on the roof of his Brooklyn studio that was only accessible online. All told, solo online-only presentations have yielded the gallery more than $20 million since last April, Soboleva said.

Arternal founder Sean Green with Faith Wilding, Euronyme & Ophion, (1977–78) at Anat Ebgi Gallery. Photo: Greyson Tarantino.

What Will Stay The Same: In-person visits remain important. While Stefania Bortolami is still waffling on a digital strategy, she has “doubled down on seeing art,” having opened another gallery (her third) at 55 Walker Street.

Viewers, it seems, have doubled down, too. On a Saturday in January, Rob Dimin, a partner of downtown New York gallery Denny Dimin, counted 60 visitors, even with appointment requirements and capacity restrictions. The tens of thousands of dollars banked from not doing art fairs, he said, is “freeing us up to focus on the program as opposed to focusing on the hustle.”

What’s Left to Innovate: Secure digital infrastructure and online vetting programs will be more important than ever, given the rise in e-commerce, especially as dealers transact with new clients and governments like the UK and US tighten oversight of the trade. Implementing digital systems to adhere to Know Your Client and Anti-Money Laundering rules—not to mention cybersecurity—will be a high priority this year.

There is also the looming question of the value of a physical footprint. Lockdown “was harder for some of the galleries that had larger leases, bigger spaces, and more overhead,” noted art law specialist Diana Wierbicki. “If some galleries are only doing a few exhibitions a year, does it make sense to buy and use a group exhibition space as a cost-saving measure?” Central hubs that offer ad-hoc gallery spaces like Cromwell Place in London might be the wave of the future.

While auction houses nimbly met the challenge of creating exciting and successful livestreamed sales, the future of the market will—as always—hinge on supply of good material.

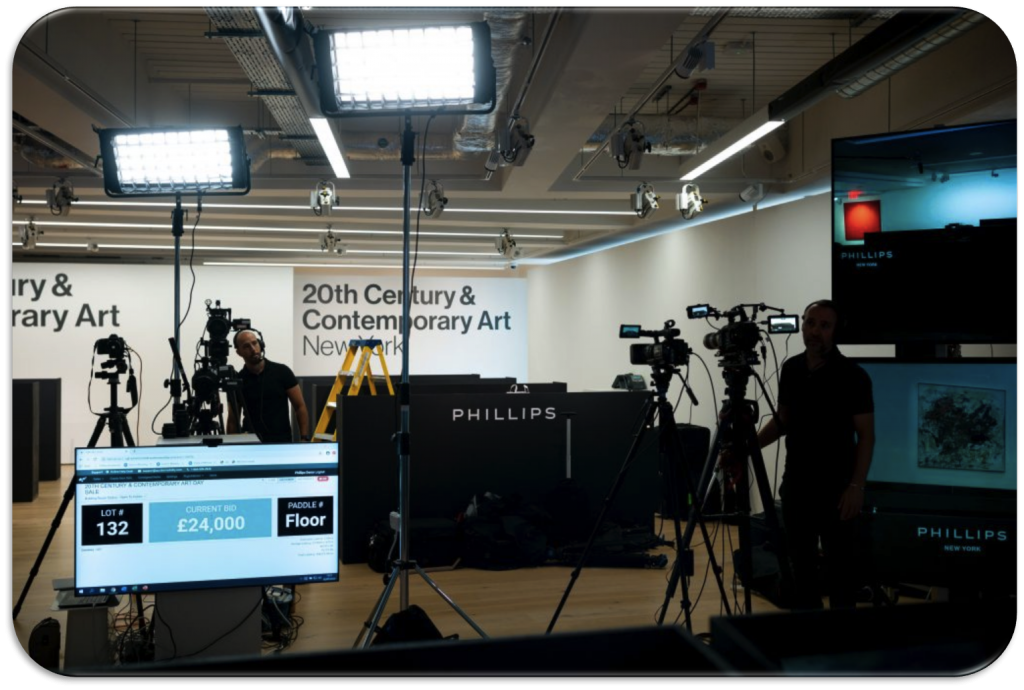

Phillips London, July 2020 livestream auctions. Photo: Thomas De Cruz. Media: Haydon Perrior. Courtesy of Phillips.

What’s Changed: The typical auction schedule historically centered on two weeks of megasales in November and May in New York, but after a year of anything goes, auction executives feel empowered to postpone based not only on public health but also on political events (like the presidential election) and the availability of material. “It’s a bit like school semesters at college,” said Sotheby’s chairman Amy Cappellazzo. “Suddenly, summer school became a viable option.”

Not everyone is pleased with this development. Wierbicki said that, while her clients were happy to have the opportunity to buy and sell in December before the Biden administration could tinker with the tax code, “it’s very hard to track when you’re used to a traditional schedule—it felt a little scattered.”

What Will Stay The Same: The need to balance supply and demand is an enduring puzzle no matter when or where sales are taking place. “In 2020,” Christie’s CEO Guillaume Cerutti said, “supply was the issue and demand was strong,” since so many would-be sellers put their plans on ice. But that may change in 2021: Some collectors will have to downsize for estate purposes, while others may be encouraged by surprisingly buoyant results. The next problem will be figuring out what to keep funneling into online sales when live auctions return.

Phillips London, July 2020 livestream auctions.

Photo: Thomas De Cruz. Media: Haydon Perrior. Courtesy of Phillips.

What Will Become Truly Hybrid: Client relationships will follow a new model—for good. David Norman, chairman of Phillips, said that pre-pandemic, his favorite part of the job was throwing open the doors to an auction preview after months of preparation and business getting. Champagne and gossip would flow.

Last year, he found himself giving more “walkthroughs” via individualized FaceTime tours to clients cozied up in front of their fireplaces in Aspen or perched in their backyards in Palm Beach. “I hold my phone up and say, ‘Let’s walk into the galleries together,’” he noted. Flipping the screen to look at a canvas, he might ask an art handler to take a work down and examine it under the black light, just as in real life. On the bright side, “I don’t have to worry about wearing nice shoes.”

What’s Left to Innovate: The drama of quarantine prompted unlikely collaborations between fairs, dealers, auction houses, and even luxury brands. (Bulgari sponsored Sotheby’s Old Master Week in January, outfitting the auctioneer and staff in the brand’s jewels.) Now that the borders have been breached, look out for more partnerships like those of Christie’s with China Guardian and Phillips with Poly in Asia, as well as auction-art-fair hybrids like Christie’s recent project with the 1:54 contemporary African art fair. “When the market is shrinking, when fairs are canceled, there is a mutual interest in collaborating to keep the market alive,” Cerutti said. “Collaborations are already effective. The challenge is to make them more frequent.”

If any art-market players could be declared winners in all this upheaval, it would be the appraisers. Collectors took advantage of the lockdown to update insurance policies, use art as collateral for loans, and get a jump on financial planning—all of which requires these specialists’ expertise.

What’s Changed: Pricing is more transparent. Instead of having to scour art-fair aisles and awkwardly interrupt gallery directors to ask for prices, appraisers were able to suck up copious figures with a strike of the keyboard to track the so-called “comparables” they use to determine fair market value.

Primary-market information is particularly valuable in the postwar and contemporary art sector, where, as appraiser Sharon Chrust put it, “prices change dramatically, in a very short time, on a regular basis.”

It is no exaggeration to say that increased price transparency—a trend that fair organizers and dealers agree is likely to continue beyond the pandemic—has allowed experts to beef up their spreadsheets in a way that will serve the field for years to come.

What Will Stay the Same: Dealing with collections of a certain scale continues to be a challenge, pandemic or no pandemic. For a recent estate appraisal at a gallery—with a total of 850 works—Chrust had to settle for a smaller sampling based on what art handlers were able to bring out at one time. Digital images had to suffice for the rest. “No matter how high the resolution is on a digital image,” Chrust said, “there still remains a limitation in the viewer’s ability to absorb the entire work as one would if they were seeing it in person.”

What’s Left to Innovate: A comprehensive way to capture both primary and secondary market pricing is needed in an increasingly fast-moving landscape. While online art fairs have made primary prices somewhat easier to track, the increased volume of and new formats for online auction sales have resulted in increasingly obscure public results. Not only are lots that fail to meet their reserves left out of public records, but a growing number of works are being withdrawn on the day of the sale because of a lack of interest, making the true level of demand difficult to discern. What’s more, Elizabeth von Habsburg noted, “the virtual death of the printed auction catalogue has some consequences, in that there is no longer a permanent record of what was in any given auction.”

Of all the sectors in the art market, art fairs have arguably been hardest hit. Without a physical gathering space or event-driven demand, “the only works that sell are works that would sell in any environment,” said the dealer Rob Dimin. “It’s not unique to the fair.”

Denzil Forrester in conversation with Victor Wang, at Frieze Live in

London, October 2020. Photo: Deniz Guzel. Courtesy of Deniz Guzel/Frieze.

What’s Changed: It was long an open question whether art fairs could translate the social shopping experience to the web. Now, we have an answer: no. A scant 10 percent of collectors bought work from online platforms “often or always” during the yearlong period ending in August 2020, according to a recent survey.

After more than a year of adapting to a fairless environment, expect dealers of all sizes to get selective about which events they take on. Two years ago, Dimin said, he would typically be gearing up for fairs in Europe, Asia, and Latin America, as well as four in the US. “Now, we’re just going to be concerned about two fairs in the US,” he noted. “We’re focusing all our foreign efforts on Asia.”

What Will Stay the Same: In-person experiences are still the best way to drive commerce. “The number one thing that keeps our galleries awake at night is meeting new clients,” said Noah Horowitz, Art Basel’s director of Americas. “Client engagement regeneration [comes from] getting in front of new people.” In January, Art Basel Hong Kong offered dealers who might be stymied by travel restrictions the opportunity to keep their galleries front and center by taking out a smaller space manned by an Art Basel staff member for a reduced price. (Call it a “ghost booth.”) In a nod to the importance of human contact, the fair mandated that the gallery staff still be reachable by phone for the event’s full opening hours, time difference be damned.

What’s Left to Innovate: Just as Blockbuster’s failure to translate to the web opened the door for Netflix, the face-plant experienced by online art fairs has created an opportunity for other art e-commerce models to fill the breach.

Fairs are now sorting out how to offer a scaled-down physical experience—supplemented, rather than supplanted, by a robust virtual program. “Now is the time to think about a total redesign,” said Tony Karman, the president of Expo Chicago. “What size of fair are we? Do we almost go back to 2011 levels?” he asked, referring to the first year of the event.

The Outsider Art Fair found success in Paris with an IRL exhibition curated by Alison Gingeras featuring highlights from exhibitors, who showed their full offerings online. Frieze New York is planning a 60-gallery event at the Shed in May, along with digital and offsite programming.

“We’re striving to have some small in-person events,” said Frieze consultant Loring Randolph, “together with the in-person event that is the fair itself.”

This story originally appeared in the Spring 2021 Artnet Intelligence Report. To download the full report, which includes in-depth data analysis of auction performance in 2020, a look at the future of the experience art economy, and a profile of the best bad painter out there, Robert Nava, click here.