Art & Exhibitions

Joseph Kosuth: Hot, Bright, and Requiring Lots of Explanation

Some outside discussion is required when pinning down meaning in the artist's works.

Some outside discussion is required when pinning down meaning in the artist's works.

JJ Charlesworth

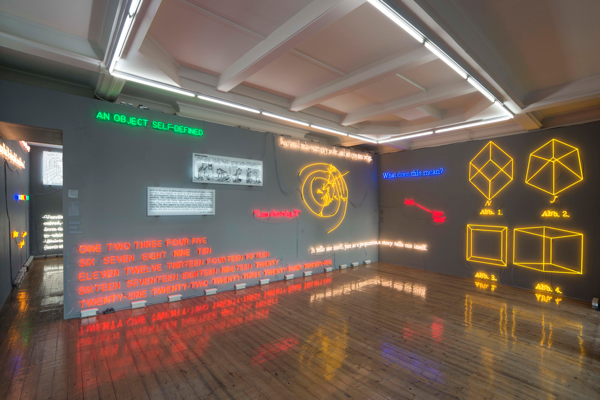

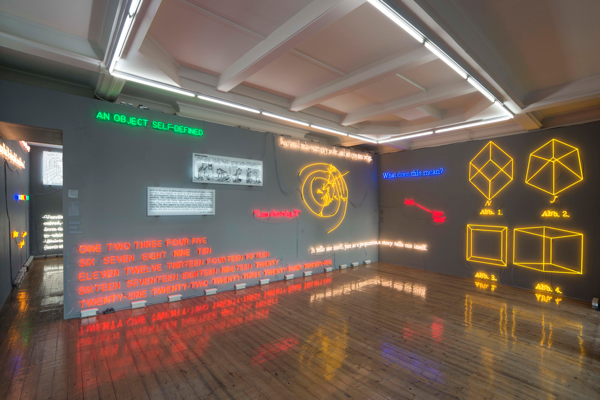

Installation view, Joseph Kosuth’s “Amnesia: Various, Luminous, Fixed.” at Spruth Magers London.

Photo: © Kris Emmerson, courtesy Sprüth Magers.

Grey-painted walls decked with neon script like Christmas lights or a science museum exhibit for kids, the gallery hums with hot reds, greens, yellows, blues and stark whites. Stuffy with the heat from the neons and their transformer units, Joseph Kosuth’s show “Amnesia: Various, Luminous, Fixed.“ is assembled from works ranging across the old American conceptualist’s career, from 1965 to 2011, their shared property being that that they’re all made of neon.

It’s an extreme abbreviation of an artist’s work, condensed and compacted in this fairground form, especially an artist who casts such a long shadow over the history of contemporary art, for his role in the turn to “conceptual art” in the mid-1960s. “Concept art is a kind of art of which the material is language,” wrote avant-gardist Henry Flynt in the early ’60s, and Kosuth’s neons here are nothing else (apart from the incursion of one or two diagrams and a couple of philosophically inclined cartoons on back-illuminated Perspex, one of them a brilliant Calvin and Hobbes strip). Kosuth’s early roots were in analytical philosophy, and his neons fiddle with that legacy: it’s language that considers the nature of language as it describes the world—as it makes meaning and creates objects. So the earliest here, Five Fives (to Donald Judd), from 1965, is five rows of five words, of the numbers one through to 25 which stack up like bricks in an unfinished wall. Like the nearby phrase “An Object Self-Defined” (Self-Defined Object [green], 1966), or the four colored words of Four Colours Four Words (1966) it’s a test of the relationship of a thing to an idea to a word. These texts short-circuit the question of how visual art relates to how we speak about it, dating from a period when modern art had gotten stuck with a certain idea of what modern art should look like, and how it should be talked about.

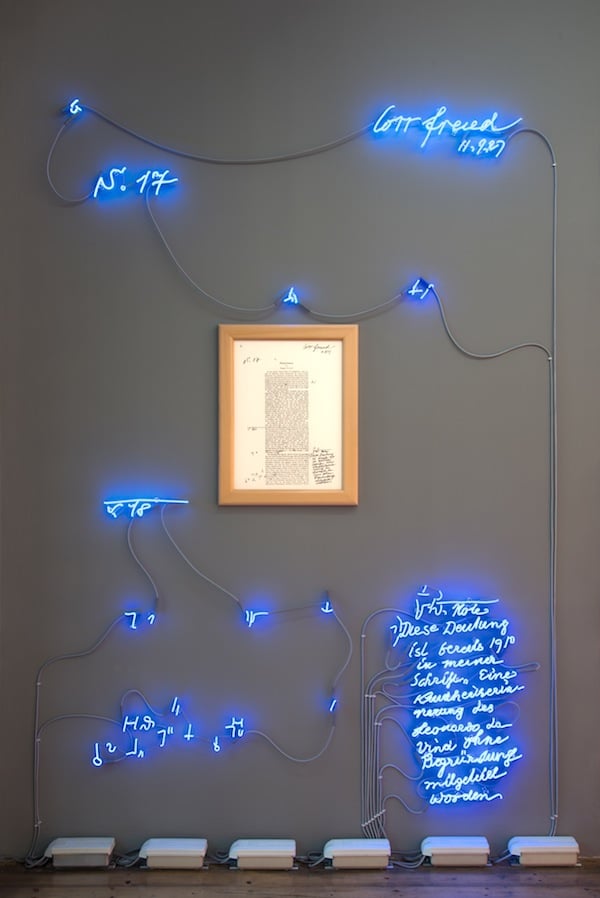

Those early works are succinct and uncompromising in how they give shape to the philosophical perplexities of form and idea—everything you need to know or think about is contained right there in front of you, where visual or physical forms merge with their own descriptions. But maybe there’s only so many times you can pull off such magic tricks as an artist—later works are more elliptical, happy to digress into erudite backstory and quotation, often from the history of philosophy, science and literature, and from those great thinkers for whom language and speech was a core preoccupation—Ludwig Wittgenstein, Sigmund Freud, James Joyce, Samuel Beckett. So, over by the entrance is a neon which scales up all the typographical corrections that Freud made to the galley proof of the first page of his book on fetishism, bright blue squiggles surrounding a framed reproduction of the page (Fetishism Corrected, 1988). Round in the next room, L.W.’s Last Word (cobalt blue) (1990) is an arcing slash of neon scribbles of the German word sprache, (speak), crossed through, which, according to the little wall notes, was Wittgenstein’s last written word before he died.

To look at these means, inevitably, having to think one’s way into these huge intellectual vistas, which is perhaps why the walls are scattered with little wall texts by Kosuth, solemnly explaining the thinking behind various works. Kosuth’s wall texts are curious things—surreptitiously reaffirming the artist’s place in art history, making little value judgments (“Fetishism Corrected, 1988) is one of the most important of the later Freud works,” explains one text matter-of-factly), and in a broader sense attempting to control and regulate the way in which we might begin to get something out of the work. They’re like curators’ texts in a world where curators don’t exist, and in an odd way they show up one of the great tensions to have come out of conceptualism: you often have to take the artist’s word for it, since the work offers little more than a huge arrow pointing elsewhere; while the function of critics and curators has been dismissed, or incorporated into the whole of the artist’s activity.

As one little text panel declares, “Joseph Kosuth’s point of view since the beginning of his work in the 1960s is that artists work with meaning, not simply with forms and colors.” But what’s most vivid about “Amnesia: Various, Luminous, Fixed.” is precisely the cheerful excess of forms and colors, since the meanings Kosuth is working with are in many ways deferred, and require you to have a discussion about some subject outside of the work to reassemble them. They work like advertising signage for big ideas, slogans for an artist’s undoubtedly profound intellectual engagement with the thought of his era. But as a critic, or as any viewer to this hot, bright exhibition lighting up a grey London winter day, are we here to discuss other people’s ideas, or the artist’s art? Or can’t we tell the difference any more? It’s a tough call, and Kosuth is always a hard sell.

“Amnesia: Various, Luminous, Fixed.” runs at Sprüth Magers London through February 14, 2015.

JJ Charlesworth is a freelance critic and associate editor at ArtReview magazine. Follow @jjcharlesworth on Twitter.