Analysis

Kenny Schachter Lays Bare the New Auction Season—Who’s Up, Who’s Down

Art has become everything to everyone.

Art has become everything to everyone.

Kenny Schachter

I know this sounds like a set-up for a Richard Prince joke painting but it’s true: I went to a shrink to help cope with anxiety issues last week and when he found out what I did for a living, all he could ask about over the course of the next hour was art market advice; including who bought the Picasso for $180 million and whether or not Wifredo Lam‘s (1902-1982) recent Pompidou Centre show would improve his market (still not a strong buy).

I knew art was a religion to some but now realize it’s become everything to just about everyone. It was time for a new therapist, though not before I asked him to put me in touch with some of his well-heeled clients—for a fee share of course.

Every day in the newspapers and on CNN, you rarely if ever hear about simple good deeds or successes in life, just a barrage of violence, doom and gloom; in the art market of late, it’s the same (I might even have been guilty of this in the past myself) whether in Bloomberg or the International New York Times—both having recently reported on the downfall of hapless Lucien Smith (b. 1989), which is so two auctions ago, by the way. Smith, all of 26 years old, is alive and kicking and mighty capable of making more good art; I’m admittedly a sucker for his smushed pie paintings.

He even happened to sell a few works (one at the top of the estimate) in some of the four interim contemporary auctions at Phillips, Christie’s, and Sotheby’s in September in London and New York that cumulatively raised about $35 million in total. But who wants to hear about Lucien’s successes in the face of an onslaught of such negativity, de rigueur in today’s world of art market reporting?

So I’ve come up with a new shtick for this review: a (mostly) kinder, gentler affair looking at the winners (all 6 of them—kidding), which is albeit a little out of character for me. But before I do so, these nebulous filler sales represent an auction glut that might have been better served being staged as Internet-only sales as the overall quality never amounted to much.

This is in light of yet another round of upcoming October sales staged during the Frieze fairs (another kind of excess) followed on the heels by the notorious November New York auctions, known for knocking down a series of record prices, only to be repeated yet again during the next cycle in the Spring. And that is after the FIAC fair in Paris in October, the Basel Fair in Miami in December, and the London auctions in February. See what I mean? With loop after dizzying loop on the fair/auction merry-go-round, you can appreciate why I need an art-neutral therapist.

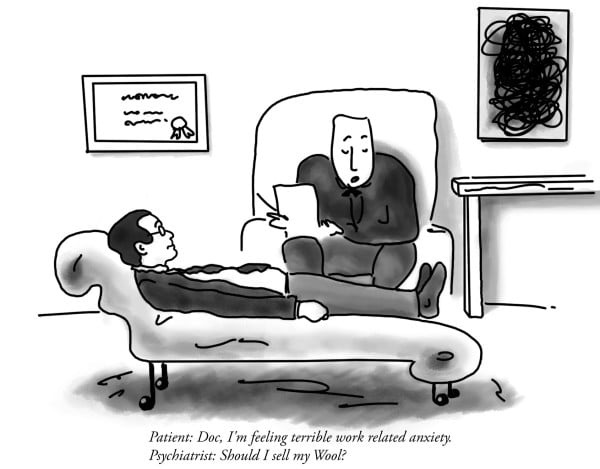

Phillips New Now, New York, September 17th

What’s new now at Phillips? Not much. Though I am on a mission to avoid being impish, they certainly make me strain. Watching the sale online, the auction house couldn’t manage to coordinate correlating the correct image on screen to the lot on offer and subsequent to the event, I couldn’t even get the online results while researching for this article. When trying to do so, I was only met with a cheeky piece of art by Rob Wynne from 2006, entitled Oops! What a perfect description, perhaps it should become incorporated into the Phillips corporate logo (more on those to come). Damn they do a good job thwarting my efforts to be sweet.

As I’ve mostly healed from a previously reported taxicab accident that left a two and a half inch scar across my face, the market for work by young contemporary artists has been torn asunder. There are always exceptions and a glaring one was the curiously named young LA-based painter and performance artist Math Bass (b. 1981) whose second work at auction achieved a stunning $68,750 on a presale estimate of $15-$20,000; and only six months ago, her first publicly-sold painting made $17,500 on an $8-$12,000 estimate.

I guess the new math is not so different from the old math when it comes to those still perceived as the latest hot young thing. Bass’s small formatted paintings are comprised of odd, disparate hieroglyphs including geometric shapes, alligator (or crocodile?) heads and plenty of matches and cigarettes. Though I’ve never smoked tobacco, I’ve always been a fan of art with cigarettes, especially anything by Philip Guston. Not to mention, in the 1970’s, Sotheby’s even marketed their very own brand of signature cigs! Those were the days.

German artist André Butzer’s (b. 1973) wildly colorful, cartoonish, good-bad paintings could be said to hail from the Playskool (a purveyor of toys for kindergartners) school of art. And he could also be said to be in the midst of a market moment, his vividly colored reddish-orange canvas strewn with juvenile, crudely rendered figures combined with shards of abstraction, sold for $143,000 (which tied with his record set 6 months earlier at Phillips for the sale of Calvin Cohn Pong!) on an estimate of $25-$35,000. Butzer is a relatively young artist seemingly in a moment of ascendancy in these harsh times for such painters.

Gerhard Richter, Haggadah (2006).

Image: Courtesy Christie’s.

Christie’s (first) First Open, London, September 23rd

Unlike Sotheby’s and Phillips (when they get their shit together to post results), Christie’s doesn’t show pre-sale estimates without having to click through and rather conveniently for them, doesn’t bother to post unsold works from their sales. Very annoying.

They also take the prize for religious insensitivity staging an auction on the highest of holy days of Judaism, Yom Kippur. When I queried a top New York-based official of the company, he stated: “Typical British behavior” lovely. To atone for their sins, Christie’s offered Gerhard Richter’s (b. 1932) Haggadah (a Jewish prayer book), a 2014 print in an edition of 500 that fetched £32,500 ($49,823) against a presale estimate of £6-£8,000.

Allan Kaprow (1926–2006) was famous for his performative Happenings in the 1960’s; he certainly made another kind of happening when his appropriately titled painting from 1956, Hysteria, made £140,000 ($215,000) on a £5-£7,000 estimate. Reminds one of the recent nuttiness of art price inflation but seems a perfect example of a little reality testing setting into the market, which never hurts. Why not try something interesting, less obvious for a change?

A fairly bland, early Rudolf Stingel (b. 1956) painting—before he developed his more recognizable style of painting—attained £152,500 ($232,398) with an estimate of £45-£65,000, while another André Butzer painting, which, at more than 15 feet, was prohibitively oversized—a real market impediment—still managed to make nearly $100,000 (est. £15-£20,000). That goes a long way towards indicating his recent market move is cemented.

Albert Oehlen, Verweis (2006).

Image: Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Sotheby’s Contemporary Curated, New York, September 29th

Uncharacteristically in the field of contemporary art, Sotheby’s led the pack with a series of standout results including Alexander Calder’s (1898-1976) fittingly titled The Gamblers from 1972, which made $250,000 (est. $40-$60,000) for the gouache on paper; a perfect example of giving the people what they want, as Calder is a perennial crowd pleasing money spinner. And from far afield, an Alfonso Ossorio (1916-1990) ink-on-paper, Fourth of July (est. $12-$18,000), knocked it out of the park at $112,000; who’d have thought?

Kooky, UFO-loving, shiny-fetishistic abstract sculptor John McCracken (1934-2011) launched into outer space achieving $562,000 (est. $180-220,000) for Nine Planks II from 1974; David Zwirner representation never hurts, ask Oscar Murillo (b. 1986), the onetime poster boy of flip art, ironically the last of the genre standing.

While Kenneth Noland (1924-2010) took flight with Winged (1964) all the way to $514,00 on an estimate of $40-$60,000, Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008) hit $225,000 (est. $60-$80,000) for a hanging fabric and cardboard work from 1975. Rauschenberg is finally on the up and up and rightly so—long overdue—but I guess painting by the mile during the 1980s didn’t go far in helping to further his prices.

Jonas Wood (b. 1977) continues his upward trajectory ahead of his monstrously anticipated Gagosian show (in terms of its market) where he allegedly won’t give Larry G. access to the works, not only prior to the opening, but even a week after, till the artist get’s the lay of the land on demand.

Holding the behemoth at bay is a huge act of not so much market resistance than savvy. A canvas bearing his lushly painted potted plants from 2007 made $100,000 (est. $40-$60,000). Jeff Elrod’s (b. 1966) Study for Echo from 2013 (est. $25-$35,000) sold for $62,500; one of his vertiginous Echo works that stood only 15 inches high (and 21 inches wide). Expect him to break into Albert Oehlen territory in painting’s financial sweepstakes.

A previous market darling with a record of more than $6 million at auction for an Epson print on canvas, Wade Guyton’s (b. 1972) X Poster in an edition of 100 from 2007 made $31,250 (est. $7-$9,000), an amazing feat considering a friend bought three iterations of the print for $1,000 each only a month before, giving new meaning to caveat emptor. If you happen to know the winning bidder, keep it quiet please or they are likely to blame me, the messenger. And lastly, Amy Sillman’s (b. 1955) painting entitled DOG (2007), sold for $162,500 (est. $80-$120,000). Moronically, Georg Baselitz (b. 1938) has gone on record stating all female artists are dogs when it comes to their price performance at auction; such idiocy is enough of a reason to dismiss the imbecile altogether.

Damien Hirst, Beautiful, Exotic, Erotic, Divinely.

Image: Courtesy of Christie’s.

Christie’s (second) First Open New York, September 30th

Wrapping up, sorry to have droned on so long about stuff so utterly inconsequential, a piece of Calder jewelry zoomed to $203,000 (est. $70-$100,000) confirming: what is art in some cases but mere burnished baubles? Go ahead ask Jeff. A Michael Goldberg (1924-2007) painting from 1958 made $269,000 (est. $100-$150,000), a perfect example of people pausing to reflect rather than continue to blindly lurch.

And lastly, you can all breathe a sigh of relief now, none other than the rocket man himself, Damien Hirst (b. 1965), spun $509,000 from a spin painting (est. $250-$350,000). The 1995 work titled Beautiful, Exotic, Erotic, Divinely, Deep, Devil Painting encourages us not to believe everything we read. Maybe the distorted puff piece in the September 17th edition of The Wall Street Journal by the normally level headed Kelly Crow Betting on a Damien Hirst Comeback really did work. Well-done team Jose Mugrabi & Co.

More on Damien

Mind if I don my critical cap for a sec? I hit up my long-term, best-est friend and art world adviser (of insider information), Deep Pockets, who informed me straight away that the alleged $33 million purchase over the last three months by the above-mentioned Mr. Mugrabi of recent Hirst works reported in the Journal, was in fact more like $20 million spread over years, not months.

Besides opening his Newport Street Gallery in London, a free museum and truly generous enterprise, leading off with a show of paintings by minor modernist John Hoyland (1934-2011) from Sheffield, UK, of which I can’t find much else to say about, Hirst has apparently been gearing up for his latest body of work begun shortly after his near suicidal Beautiful Inside My Head Forever single-artist sellout (in more ways than one) hybrid exhibit/auction at Sotheby’s in 2008. I even heard the artist financed some of the production for the new blowout exhibit, soon to premier at an undisclosed location rumored to be an institution, perhaps one of Francois Pinault’s museum venues. Which all makes perfect economic sense for such a mid-sized company as the artist has become.

Digging deeper than Deep Pockets, I succeeded in piercing the veil of Science Ltd., Hirst’s tightly controlled corporate entity, and found a little canary willing to snitch. Even Damien’s nearest and dearest have been required to sign confidentiality agreements before allowed a glimpse of the upcoming fanfare, sure to be at the very least a spectacle. The show will be entitled Treasures, and on the painting front the ubiquitous spots, the further production of which were repeatedly sworn off by the artist, have been replaced with a grid of little round corporate logos gilded with gold-leaf edges. Oh lord the dearth of ideas sparking through already.

And the masterpiece: life-sized nude casts of his accountant Frank Dunphy (b. 1938) the 77-year-old subject of a recent book of drawings, Portraits of Frank, the Wolseley Drawings) as the Greek god Pan and Rihanna (b. 1988) as his nymph. Mind you, Pan was the god of shepherds and, as such, Dunphy’s done an admirable job marshaling the artist’s formidable stash of cash. But like Koons, you can’t, nor wouldn’t, want to miss it no matter what your proclivities on the issue.

Math Bass, Newz! (2014).

Image: Courtesy of Phillips.

Conclusion

Speaking of gold, art appears to have stolen the luster off the once bellwether vehicle for gauging and storing wealth: must be the visual (and social) dividend that the metal alone can’t equal. Besides, gold is no match for art’s transcendent intellectual capacity to enrich the mind like great music, poetry, literature, or architecture, though a lot of over-fabricated production has come to resemble nothing more than trifles for the ultra net worth—the progeny of the high net worth—players.

Between all the September sales, the notion of slim pickings was stretched to the extent that a vulture would be given cause for pause. Nevertheless, the houses probably make more revenue from these bread and butter bulk sales of mediocrity than in their flagship marquee evening events chock-a-block with super sexy lots accompanied by micro margins; the only way to pry prized possessions from unwilling sellers. Though I can’t quite speak (positively) for Phillips performance, I did succumb to a Math Bass private treaty purchase via the fledgling house. Pardon the apparent conflict that resembles the art world equivalent of a product placement in film. Everyone says art is a largely unregulated business (which I don’t buy into), so why not?