Photo: Patrick McMullan.

Eleanore de Sole, who along with her husband Domenico De Sole is facing off against former Knoedler & Co. director Ann Freedman for selling them fake paintings allegedly by Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, took the stand Friday in the Knoedler trial in Lower Manhattan. At times, her testimony got very emotional.

Asked to describe her background, she said that she got her start in life as a typist/receptionist, making $5,000 a year, and then worked at IBM, which gave her great pride since both her parents had worked there. At the mention of her parents she began to cry, and explained that her mother was recently deceased. Her parents had also spurred her interest in art, she said, by taking her to museums when she was a child.

Related: 8 Key Points to Know About the Knoedler Trial

De Sole related her getting acquainted with Knoedler and Freedman through the recommendation of a neighbor who said they were the best in the business, so when they wanted some works by Irish painter Sean Scully, she and Domenico contacted the gallery and made an appointment. Visiting from Colorado, they stayed at a cousin’s apartment near the gallery, sleeping on a fold-out bed in the living room.

At her office, Freedman explained that she didn’t have any Scullys, De Sole said, but said she did have some “masterpieces” from a previously unknown Swiss collector, namely the Pollock and Rothko in question, which were on easels in her office, but veiled. Freedman then removed the covers and left the De Soles alone with the artworks.

Eleanore De Sole testifying in the Knoedler forgery trial.

Photo: Elizabeth Williams, courtesy ILLUSTRATED COURTROOM.

When she returned, Freedman “did a lot of talking,” De Sole said, pointing out that she herself had never heard of any of the people who had supposedly endorsed the artworks. The Swiss collector, Freedman told the De Soles, wanted the works to remain on the buyer’s wall and not be resold.

“We had purchased a Rothko at that point, a work on paper,” De Sole said. “It was the most expensive piece we had ever bought and this was six-plus times the price. To be able to have a Rothko oil is very privileged, and to see one for sale, you couldn’t not be curious.”

When the gallery sent them a several-page letter “warranting” the work’s authenticity, she said, they were satisfied, and shelled out $8.4 million.

Related: Potential Witnesses Revealed on First Day of Knoedler Forgery Trial

The trouble started in December 2011, she said.

The couple was in Miami, visiting art fairs, when, reading the paper on her iPad, she read that other buyers were suing the gallery for an allegedly fake painting.

“Its provenance was exactly what we’d been told,” she said. “I went into a shaking frenzy and cried.”

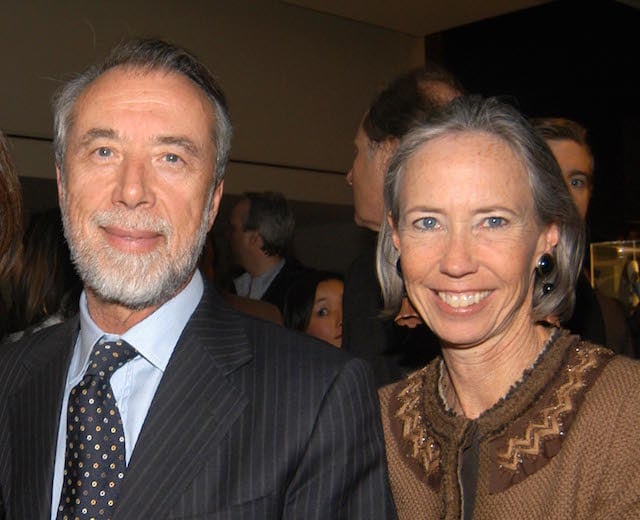

Eleanore and Domenico De Sole.

Photo: Matteo Pandoni, Joe Schildnorn, courtesy BFA.

Also taking the stand over the course of the day were two art conservators, and an art historian. Though each of the witnesses attested to Knoedler’s prestige and Freedman’s solid reputation, they gave evidence that undercut them both.

Museum of Modern Art conservator James Coddington was the day’s first witness. Asked whether he had authenticated any artworks, he said, ”I don’t authenticate works of art.” He would be just the first of the day to say that.

The lawyer displayed a document, which would be shown numerous times, which indicated that the Pollock “has been recognized by Pollock specialists, art historians, and museum curators and conservators, who have confirmed this work to be by the hand of Jackson Pollock and of the highest level of quality.”

In addition to pointing out that he had never given permission for his name to be on the list or even had any conversations with Freedman that would substantiate his name being on it, Coddington pointed out that the document also had his name spelled wrong, with two T’s in place of D’s.

Related: Richard Diebenkorn’s Daughter Challenges Ann Freedman’s Story at Knoedler Forgery Trial

Previous testimony by Earl Powell III, former director of the National Gallery of Art and of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, was then read aloud. Powell had also been included on Freedman’s list of supposed endorsers; he pointed out that he’s not even an expert on postwar painting, but rather a specialist in the 19th-century Hudson River School.

“Our conversations never focused on Rothko,” said Powell. He, too, said he had never given permission for his name to be on a list of endorsements.

Next came testimony by museum director and former Rothko Foundation head Bonnie Clearwater, who also read from a deposition. Had she seen the Rothko, which Freedman had purportedly shown her and described as coming from a previously unknown collection? (The works, supposedly from an unnamed Swiss collector, had come to Knoedler via Long Island dealer Glafira Rosales.)

“She might have mentioned a new Rothko in passing,” Clearwater said.

Art historian Irving Sandler then took the stand. A giant in the field of Abstract Expressionism, Sandler related that he had been visiting galleries, “when the weather was nice,” once or twice a week for sixty years.

Had he ever authenticated a work of art?, De Sole’s lawyer asked.

“I never have and I never will,” he said, “because it’s a specialized skill.”

What brought Sandler to Freedman’s office the day that he supposedly inspected the artworks in question?

“I was there for art-world gossip,” he said, to chuckles from the room. The Rothko was just hanging on the wall, he maintained, saying he had looked at it for maybe twenty seconds.

“I knew it was a Rothko—or it looked like a Rothko,” he said, adding that he had no doubt of its authenticity, owing simply to the imprimatur of the Knoedler name.

Freedman’s memo to potential buyers characterized Sandler, formerly the head of the Rothko Foundation, as being familiar with its 1,200-plus works. Not so, he said; most of those works had gone to Rothko’s heirs after a lawsuit by the time he came on. He knew just three or four, he said. The ones that hung in the front office.

Related: Sparks Fly at Knoedler Trial as Defrauded Buyer of Fake Rothko Painting Takes Stand

Also questioned was art conservator Dana Cranmer, whom Freedman hired to prepare condition reports on the works in question. Countless times, she testified that she had never authenticated any artworks.

Cranmer had also worked at the Rothko Foundation, as a conservator, where she viewed hundreds of the artist’s works. All the same, conservators, she pointed out, do not authenticate, adding that it’s prohibited by their code of ethics. All the same, a lawyer for the gallery then pointed out, she had signed condition reports calling the works in question a Pollock and a Rothko. She specified that that information had come from Freedman and that she had no reason to question it.

Cross-examining Cranmer, a lawyer for the gallery displayed numerous statements she had signed about the artworks in question that might read like authentications.

These included estimations like “In technique, materials, and style, it exemplifies the classic Rothko format from the 1950s.” Regarding the Pollock, she wrote that she had seen “comparable examples” of signatures. It was a “prime example of the artist’s classic style” and “a genuine example by the artist.”

Testimony continues Monday.

Additional reporting was provided by Alyssa Buffenstein.

Correction: This story originally identified a lawyer for the gallery as a lawyer for Freedman.