Galleries

Legendary Women Dealers You Need To Know, Part Two

How Virginia Dwan, Betty Parsons and Emily Harvey changed the contemporary art world.

How Virginia Dwan, Betty Parsons and Emily Harvey changed the contemporary art world.

Cait Munro

Last week, we introduced you to three incredible women who revolutionized the New York art world of their respective times. This week, find out which dealer discovered her love of art at the original Armory Show, which LA gallery held exhibitions that left critics literally speechless, and more.

Virginia Dwan at the Dwan Gallery, New York, 1969.

Source: artnet.

VIRGINIA DWAN

Virginia Dwan, named “the grande dame of the avant-garde” by the New York Times‘s Michael Kimmelman, was born in Minneapolis, an heiress to the 3M fortune. After dropping out of art school at UCLA, she opened a gallery in a Spanish Mission-style building in the Westwood section of Los Angeles. It was 1959. There, she presented works by Robert Rauschenberg, Yves Klein, Ad Reinhardt, Joan Mitchell, Franz Kline, Philip Guston and a host of other artists known for challenging the dominant aesthetic of the day. Of the 41 commercial galleries in LA at the time, it is said that only Ferus Gallery could rival Dwan in excellence. Her shows, including one that featured some of Klein’s first fire paintings, left critics literally dumbstruck—there were often no reviews, but plenty of buzz.

Robert Rauschenberg, Dwan Gallery (1965).

Source: artnet.

In 1965, right after a divorce, Dwan moved to Manhattan and opened up shop in SoHo. As Kimmelman put it, “to the extent that art dealing is a profit-making business, she failed miserably.” But, of course, we like to believe that dealing art is much more than a purely capitalist enterprise, and in that regard, she succeeded greatly. She was known for behaving with her artists more like a patron or collaborator than a dealer. The original champion of the Earthworks movement, she helped fund two of Land art’s greatest monuments: Michael Heizer‘s Double Negative in Nevada, and Robert Smithson‘s Spiral Jetty in Utah.

To much surprise, Dwan closed her gallery in 1971. Her personal art collection, which features an array of works from the movements she identified and championed (Pop, Nouveau Realism, Minimalism, Conceptual art, and land art) has been coveted by museums around the country for decades. In 2013, she gifted 250 works to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, hoping to ensure they would be seen “[by] the largest audience of people possible, not just art world types who have a to-do list,” as she told the New York Times.

Sylvia Sleigh, Betty Parsons (1963).

Courtesy: I-20 Gallery. Source: artnet.

BETTY PARSONS

While visiting the original Armory Show as a child in 1913, Parsons fell in love with art. Years later, as a young woman, she moved to Paris, got married, got divorced, and then lived off her alimony payments while keeping company with Gertrude Stein, Sylvia Beach, and other forward-thinking expatriates. She simultaneously studied sculpture at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière under Émile-Antoine Bourdelle (who was a former assistant to Auguste Rodin) and Ossip Zadkine.

In 1936, she moved to New York and quickly snagged a solo exhibition of her watercolor paintings at Midtown Gallery, which led to owner Alan Bruskin offering her a job selling art on commission. After a few years of short-lived jobs in the art world, she opened the Betty Parsons Gallery in 1946 on 57th Street. At a time when the market for avant-garde American art was minuscule, Parsons was the only dealer willing to represent artists like Jackson Pollock, especially after Peggy Guggenheim closed her gallery and returned to Europe. In addition to Pollock, she showed work by William Congdon, Clyfford Still, Theodoros Stamos, Ellsworth Kelly, Mark Rothko, and others. In 1950, she gave Barnett Newman his first solo show; Rothko and Tony Smith kindly assisted with the installation. In the words of Helen Frankenthaler, “Betty and her gallery helped construct the center of the art world.”

Though she operated the gallery until her death in 1982, many of the Abstract Expressionists whose careers she launched would eventually leave her for more commercial dealers, which she greatly resented. She moved on to another generation of artists that included Agnes Martin, Jasper Johns, and Richard Pousette-Dart. In her waterfront studio on the North Shore of Long Island, she worked on her art in her time off from the gallery. According to artist Jack Youngerman, “[she eventually] moved to the North Fork to get away from the socializing on the South Fork. Even in her 70s, she swam nude. She was a free soul.”

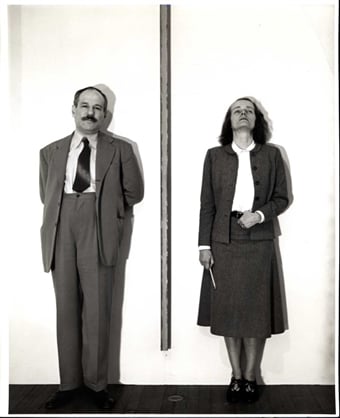

Hans Namuth, Barnett Newman and Betty Parsons (1951).

Source: artnet.

Emily Harvey during Jean Dupuy’s Exhibition, Where, at the Emily Harvey Gallery, New York, May 17, 1988

Photo: Christian Xatrec (courtesy Emily Harvey Foundation)

EMILY HARVEY

The daughter of a painter and a sculptor, it seems natural that Emily Harvey would choose art as a career path. But, when she first moved to New York in 1964, she worked a variety of jobs. It wasn’t until 1977, while working at Poster Originals, that she met and married artist Christian Xatrec, and was introduced through him to the circle of Fluxus artists working in New York. This included Jean Dupuy, who would collaborate with her and Xatrec to open Grommet Gallery (later renamed the Emily Harvey Gallery). Carolee Schneeman once said of the SoHo space: “You can always hang around, have a coffee, use the typewriter or even sleep there… It’s an art household—like a church—and we are co-religionists there.”

Like many other gallerists on this list, Harvey treated her artists as friends rather than cash cows—she bought their work for her own collection, sold their work taking smaller than normal commissions, provided space for performances and dinners, and advised them on their lives and careers. She was known for her down-to-earth style, often wearing her hair in pig tails. However, as her friend Henry Martin once said, “the most dangerous place to be was between Emily and something she wanted.”

Harvey passed away in 2003 after a battle with cancer, but not before ensuring that her legacy lived on. She established the Emily Harvey Foundation, which produces exhibitions and provides artists and writers residencies in Venice, a city Harvey knew and loved.

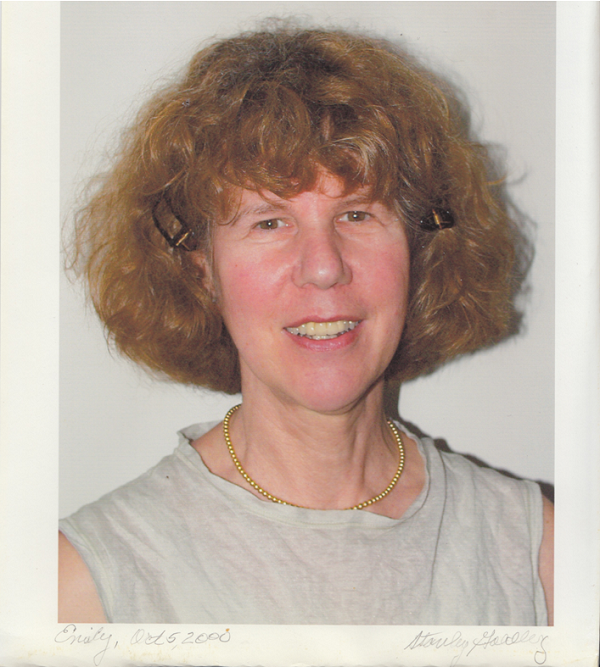

Emily Harvey captured by photographer and friend Stanley Goldberg.