Galleries

Legendary Women Dealers You Need To Know, Part One

A look at three pioneers: Pat Hearn, Eleanor Ward, and Holly Solomon.

A look at three pioneers: Pat Hearn, Eleanor Ward, and Holly Solomon.

Cait Munro

Ready for a history lesson? We’re taking a trip back in time to explore the lives and accomplishments some of New York’s greatest gallerists, patrons, and personalities. Want to know who made Chelsea an art destination first, or which now-legendary artist couldn’t sell a painting for $50 in 1953? Read on for some stories from the New York of yesteryear, and the lasting legacies of three incredible art icons who we think ought to be household names.

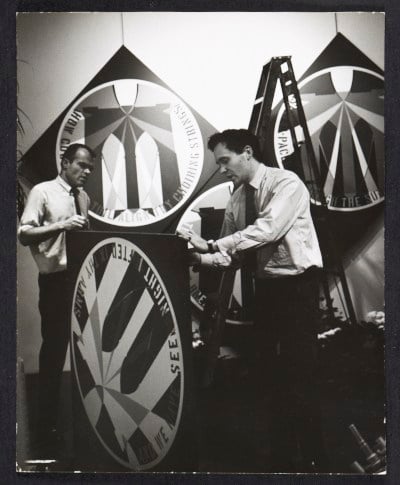

Eleanor Ward and Robert Indiana at the Americans 1963 exhibition at the MoMA

Photo: William John Kennedy. © William John Kennedy; courtesy of KIWI Arts Group.

ELEANOR WARD

Eleanor Ward began as an aide to fashion designer Christian Dior in Paris, but it was her interest in art that brought her to New York. Without any concrete knowledge of the art world, she opened Stable Gallery in 1953, which was named for its location in a friend’s unused stable off Central Park South. Initially, Stable was associated with Abstract Expressionism, however, as newer movements like Pop art came into vogue, Ward established a reputation for showing artists of varying artistic sensibilities and degrees of recognition. Thus, Stable became a spot where emerging and established artists could come together.

Ward’s willingness to take chances led to anecdotes that seem unfathomable today, like the two-man show featuring Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly that Ward mounted around Christmas in 1953. Rauschenberg, who was working as a janitor in the gallery at the time, showed his now-famous all-black and all-white paintings, which sold but were critically panned. Twombly’s graffiti-like paintings, now worth hundreds of thousands, couldn’t even be sold for their asking price of $50, despite the efforts of Dorothy Miller, then a curator at the Museum of Modern Art, who urged friends to buy them as presents.

Alan Groh and Robert Indiana installing a show at the Stable Gallery, 1964.

Photo: Nancy Astor. Stable Gallery records, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Stable is also infamous for mounting Andy Warhol‘s first exhibition of Brillo boxes in 1964. James Harvey, the designer of the original box, was in attendance at the show. According to the late scholar Arthur Danto, “Harvey was stunned… realizing that he had designed the very boxes that the Stable Gallery was selling for several hundred dollars, while his boxes were worth nothing. But Harvey certainly did not consider his boxes art.” Though understandably shocked, Harvey, along with everyone else in the gallery that night, found the whole thing rather amusing.

Thomas Messer, former director of the Guggenheim Museum, told the New York Times: “[The Stable’s] exhibitions often filled you with some doubt as to their validity, while always being very exciting…with hindsight, one realized the Stable was a memorable gallery.” Clearly, Ward was on to something, and we’re sure there are more than a few people somewhere who are kicking themselves for passing up a $50 Twombly. In 1970, Ward closed Stable, citing a distaste for the “commercialism” of the art world. She passed away in 1984.

Holly Solomon with her Warhol portrait.

Photo: Holly Solomon Estate.

HOLLY SOLOMON

Being the subject of a portrait by Warhol is certainly a good way to cement oneself as a Pop art icon, but for Holly Solomon, a life as a muse simply wasn’t enough. Also the subject of paintings by Roy Lichtenstein, Christo, and Rauschenberg, in 1969, Solomon transformed her Greene Street loft into an exhibition and performance space, which laid the ground work for what would eventually become the Holly Solomon Gallery, which she formally launched in SoHo in 1975. Through the gallery, she introduced New York to Robert Kushner, Laurie Anderson, George Schneeman, William Wegman, and Nam June Paik. She nurtured the Pattern and Decoration movement, which was known for using humble, everyday materials to produce elaborate paintings and assemblages, largely in reaction to the austerities of Minimalism.

As bold as the movement she championed, Solomon was known for her quirky, vivacious personality. Kushner has recounted how, as a young artist, Solomon showed up outside the restaurant where he worked wearing a floor-length white mink coat, with her father-in-law’s car and driver in tow. She demanded he take a ride with her and soon, the two were digging around trash bins in SoHo in search of cast-off materials for his work.

After moving the gallery uptown, then back down again, she eventually operated a by-appointment-only gallery at the Chelsea Hotel, before passing away in 2002. If you’ve heard her name recently, it may be because Pavel Zoubok Gallery and Mixed Greens Gallery jointly showed “Hooray for HOLLYwood,” an exhibition of works by artists from the Holly Solomon Gallery, in February.

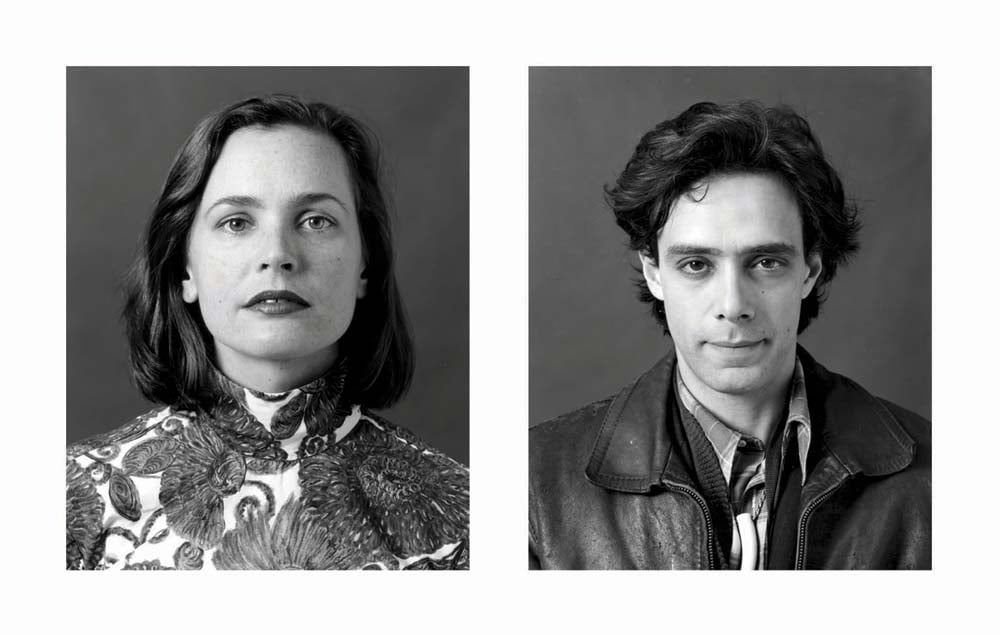

Pat Hearn and Colin De Land.

Photo: Courtesy The Pat Hearn and Colin de Land Cancer Foundation.

PAT HEARN

Pat Hearn, described by Roberta Smith in her New York Times obituary as “a bohemian Holly Golighty”, opened her eponymous gallery in 1983. There she showed the work of Philip Taaffe, George Condo, and Jack Pierson (who worked as the front desk attendant at one point). She always stayed on the cutting edge of the New York art scene, and was known for moving her gallery to neighborhoods right before they became the next hot spot (or, perhaps it was simply her presence there that made them art world destinations). In 1995, hers was one of three galleries to open on then-deserted West 22nd Street, signaling a shift in the downtown art scene that would eventually bring hundreds of galleries to the area. Before that, she maintained a space in the East Village, then expanded to SoHo right before that became the gallery neighborhood du jour.

Her beauty and panache cemented her not only as a storied gallerist, but like Solomon, as something of a muse. She is the subject of several portraits by Mark Morrisroe and Warhol. Even her Chihuahua, Chi-Chi, played muse to Ross Bleckner, Julian Schnabel, and others for a show devoted to the canine gallery attendant at Galeria Massimo Audiello. Hearn was a painter and performance artist herself, but according to Smith, she “began to realize she was more interested in other artists’ work than her own.”

She also worked with dealers Matthew Marks and Paul Morris, in addition to her husband Colin de Land, to start the Armory Show, which was originally known as the Gramercy International Art Fair and held in the rooms of the Gramercy Hotel. Once it outgrew this location, it moved to the Armory and was renamed after the famous 1913 exhibition held in the same locale.

Sadly, Hearn died of liver cancer at 45, just three years before her husband passed away. As Gary Indiana put it, “nobody who knew them has ever gotten over it.”