Analysis

So You Just Bought an NFT. Here’s What That May Mean for Your Taxes

We asked experts how regulators are responding to the latest investment craze.

We asked experts how regulators are responding to the latest investment craze.

Eileen Kinsella

In just a few weeks in the art world and beyond, NFTs went from an obscure acronym to a 24/7 obsession that has people asking questions about everything from inherent value to authenticity to security risks.

Meanwhile, many observers are trying to wrap their heads around not only what NFTs (or non-fungible tokens) actually are, but also what kinds of tax implications they carry.

Do you even have to pay taxes on an NFT? Does it matter if the token is “stored” in the US or abroad? What impact do recently tightened anti-money laundering rules have on the trade?

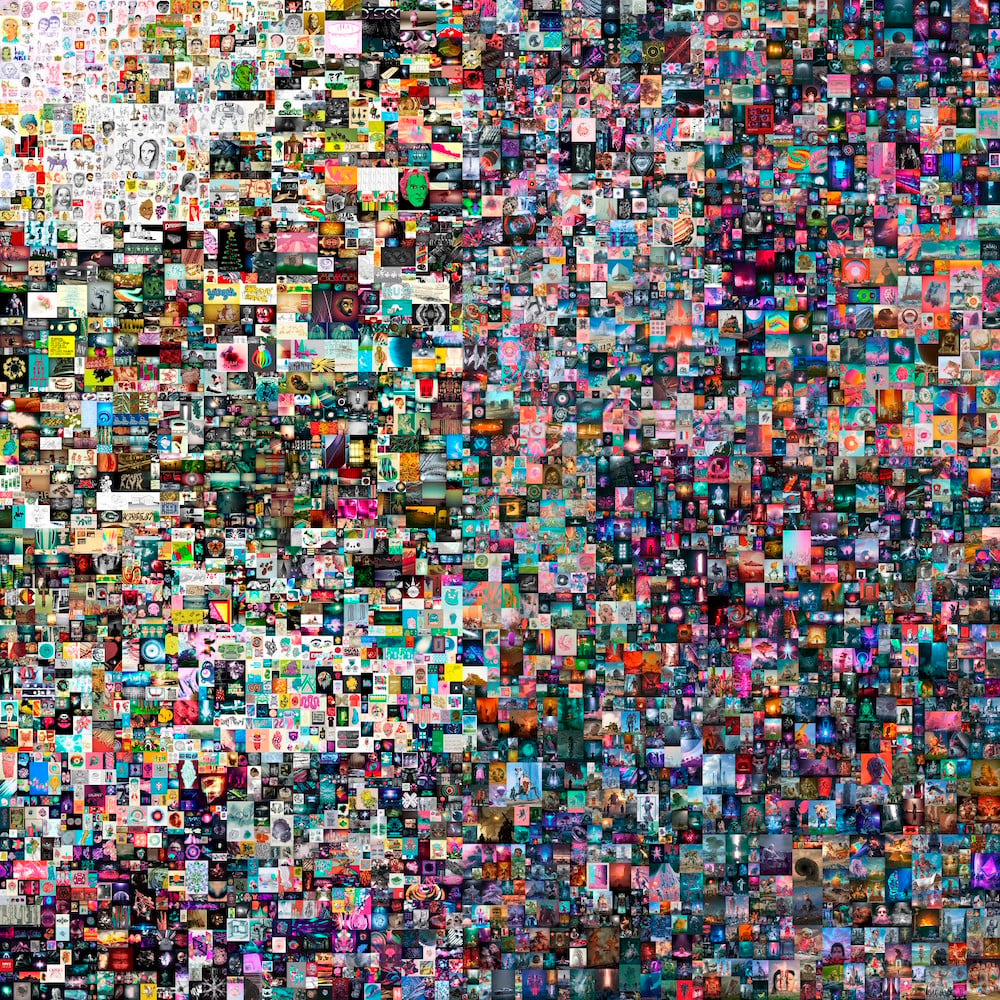

With so much money flying around (need we remind you that Christie’s sold a Beeple for $69 million?), there’s a lot at stake. So we asked tax lawyers, art advisors, and other experts about what buyers need to know about their tax liabilities before they go on a spending spree.

Beeple, Everydays – The First 5000 Days NFT, 21,069 pixels x 21,069 pixels (316,939,910 bytes). Image courtesy the artist and Christie’s.

Any collector who buys a painting in New York owes state use tax because paintings are physical goods. What about NFTs?

The simple answer is no.

New York State’s sales tax law was enacted more than 50 years ago, when the very concept of digital art would have seemed straight out of The Jetsons, says attorney and art law expert Thomas Danziger.

“The tax law was always intended to apply to tangible personal property,” he says.

“A purchase of an NFT is in essence a purchase of a piece of code in the blockchain—a digital asset,” says Diana Wierbicki, partner and global head of art law at Withers. “Therefore, an NFT should be considered intangible property, not subject to New York sales tax.”

But Wierbicki adds that, with the incredible sums now being shelled out for some NFTs, “it would not surprise me if New York decided to revisit this issue in the future so this is an issue to monitor.”

Still, Danziger notes that amending sales tax rules to include intangible properties like NFTs “would raise a host of legal and philosophical issues, including where, exactly, the NFT is located for tax purposes. Would its location on a server in New York be sufficient physical presence in the state for taxation? And if intangible NFTs are subject to New York sales tax, why not stocks and bonds traded electronically on the NASDAQ or New York Stock Exchange?”

“A sales tax applied to NFTs might raise some revenue for New York State,” Danziger adds. “But the one group that will definitely get rich off this will be the tax lawyers hired to litigate this issue.”

What about capital gains tax? Any collector who buys a painting for $1,000 and sells it for $100,000 will incur a tax bill on the difference. Is it the same case for NFTs? What if a collector buys and flips an NFT that has doubled in value?

Federal capital gains taxes apply to properties that are owned as investments. This typically includes properties that are not first homes, artworks, cars, stocks, bonds, and collectibles.

So yes, NFTs qualify.

“This means that for a collector or investor, but not a dealer who holds NFTs as inventory, NFTs should be treated as a capital asset,” Wierbicki says. “Upon the sale of an NFT, the capital gains tax would be imposed at the short-term or long-term rate, depending on whether the owner has held the asset for over a year.”

Short-term rates, which kick in when an asset is sold after being held for less than one year, are higher than long-term rates.

What if I used cryptocurrency, like Bitcoin or Ether, to buy my NFT? What are the tax implications?

Things get a little tricky here, if only for the simple reason that NFTs and cryptocurrencies are so tightly linked to one another. While you don’t have to use cryptocurrency to buy an NFT, many buyers do so, including the purchasers of the $69 million Beeple.

The Internal Revenue Service of the United States has a webpage with more than 45 frequently asked questions about cryptocurrency, as well as specific language on 2020 income returns asking taxpayers whether they have “received, sold, sent, exchanged, or otherwise acquired any financial interest in virtual currency” in the past year.

In other words, the government is starting to take cryptocurrency seriously.

That may seem overwhelming, but the IRS rules are reasonably clear, says art advisor Todd Levin. Let’s say you bought a unit of Ether a few years ago for $100, and it’s now worth $1,800. The IRS considers Ether a capital asset. So if you use it to purchase an NFT, that “creates a taxable event,” Levin says.

“That’s it, end of story. From the IRS point of view, you’re not spending currency, you’re spending an appreciated asset,” he adds.

So, similarly to if you sell a painting at auction that significantly appreciated in value since you bought it, you’re required to report your capital gains on your tax filing for that year.

What if I donate my NFT to a museum? Can I get a tax break?

“This is very new territory so we will be watching the space to see how the regulations evolve,” Wierbicki says.

But for now, the simple answer is yes—within certain limits.

“If you donate it to a museum, you can get a benefit for that like any other artwork, as long as it’s IRS-vetted and done the right way,” Levin says.

In short, if a collector donates an NFT that has been in their collection for at least one year to a museum, it may be eligible for a charitable contribution deduction in an amount equal to the fair-market value of the property.

Tighter legal regulations aimed at cracking down on money-laundering in the antiquities and art trade first cropped up in the UK in early 2020 and more recently in the US. The laws require that art-related businesses identify whomever is the “ultimate beneficial owner” in a sale, making it harder for collectors to conceal their identities. Will this affect NFT sales?

It’s still early days, explains Susan Mumford, co-founder of ArtAML, a company that facilitates customer due-diligence checks for dealers.

However, for the time being, “NFTs are a type of cryptoasset that don’t fall under the definition of ‘work of art’ in the UK’s money laundering regulations,” she says. “NFTs effectively mimic cryptocurrencies and could be used in similar ways, leading to similar risks. In reality, they are more akin to investment vehicles than tradeable art.”

In other words, watch this space.