People

As She Prepares to Release Her Autobiography, Judy Chicago Reflects on What It Takes to Preserve an Artistic Legacy

At 81, Chicago’s opportunities continue to multiply.

At 81, Chicago’s opportunities continue to multiply.

Arden Fanning Andrews

In these turbulent times, creativity and empathy are more necessary than ever to bridge divides and find solutions. Artnet News’s Art and Empathy Project is an ongoing investigation into how the art world can help enhance emotional intelligence, drawing insights and inspiration from creatives, thought leaders, and great works of art.

It’s noon mountain time, and Judy Chicago is in her kitchen. “She makes the best coffee,” her studio manager says while positioning the camera toward the sunroom sofa bathed in Belen, New Mexico light.

Coming into frame and taking a seat, Chicago wears a pink hoodie over a t-shirt with “It’s A Judy Thing (You Wouldn’t Understand)” emblazoned across the front. At home, the artist, educator, author, and self-described humanist shares 7,000 square feet with her husband, photographer Donald Woodman, and her team. “Downstairs is all commercial,” she explains. “Studio, office, storage.”

Tuxedo, a black cat with a white patch of fur in the shape of a cravat, joins her on the cushions. Hanging above them is a blown-up scene Woodman photographed at last year’s pre-pandemic Dior Couture presentation, for which the house’s creative director, Maria Grazia Chiuri, commissioned Chicago to collaborate on an installation that ultimately arrived as an enormous goddess-shaped venue in the gardens of Paris’s Rodin Museum.

On display inside, hand-sewn banners (made by women in Mumbai through a program focusing on embroidery and empowerment education) read the eternal question: “What If Women Ruled The World?” The same query, credited to Chicago, appears within Rizzoli’s Her Dior: Maria Grazia Chiuri’s New Voice. Released this month, its cover image features a t-shirt printed with another famous phrase by Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: “We Should All Be Feminists.”

Chicago, who will be one of nine members of the National Women’s Hall of Fame Class of 2021, wonders aloud if her classmate Michelle Obama will be in attendance at the October induction in Seneca Falls. “They’ve actually been trying to do this for some years, but this is the first year I’ve been able to go,” she says. “And one of the requirements is that you have to actually go to the awards ceremony.”

At 81, Chicago’s opportunities continue to multiply. A Thames and Hudson autobiography, The Flowering, with an introduction by Gloria Steinem, is due in July. The next month, she opens her first-ever retrospective at the de Young Museum in San Francisco. And the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation, which recently acquired her print archive, is planning a catalogue raisonné.

“When The Dinner Party opened in San Francisco in 1979, the director of the museum, Henry Hopkins, who was a wonderful supporter over the years, he said to me, ‘Well, Judy, this is the culmination of your career.’ And I was not even 40!” she says. “I was like ‘No, Henry, I’m just getting started.’”

“You could say that this period is kind of a period of culmination of almost 60 years of work,” she adds.

We spoke with the artist about her art, her sense of what empathy means, and how the pandemic has forced her to focus.

Judy Chicago, Desert Atmosphere (1969). © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo courtesy of Through the Flower Archives; Courtesy of the artist; Salon 94, New York; Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco; and Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles.

It’s very exciting to witness all this. And brilliant how you’ve split your archives between institutions and created a digital research portal as a precedent for other artists.

It relates in a way to where we started about the National Women’s Hall of Fame because, of course, all that research I did about the women before me and how their work was erased made me determined that that was not going to happen to my work.

Also, I had this other kind of interesting experience when I was working on The Dinner Party. There was a design company in San Francisco that did this Chevron-sponsored traveling show about creatives, and they profiled like 16 creatives. I can remember when the lead designer, Stephen Hamilton, came to the studio, and I gave him a lot of grief because I was the only woman. And he said something so interesting to me. He said, “Judy, the criteria for inclusion is not only do you have to have made a significant body of work, but you have to have documented it, and most women don’t do that.”

Now, I’m sure that’s changed, but one woman called me in a kind of panic. She’s like 89 years old and she’s trying to figure out what to do with her work. She was going to give it all to a museum, there was a friendly museum director, and then he was gone.

It falls on you to then advocate for and document your own work.

It’s not fair. I see some of my male artists peers, they’re not worried about it. They have powerful galleries, they have wives, they have children. You know, we don’t have children, Donald and I. And also, then it becomes the children… that’s all they get to do is take care of their parents’ legacy.

And look at what’s happened with the pandemic in terms of women and their work. I mean, why is anybody surprised? What women do doesn’t count. It doesn’t matter if it’s child care, house work, or making art.

Empathy has played a role in your work for decades, for women and for all living creatures. Is it a factor for you even more so now considering the divisive times that we’re experiencing?

Well, it’s very interesting because when Claudia Schmuckli was first working on my retrospective with de Young Museum [in San Francisco], she was originally going to call it “Judy Chicago: The Process of Empathy.” Which, I thought that was a great title. She had been looking at a lot of my work by then, and I mean, the question of empathy actually bumps up against the question of who owns human experience.

When we were working on The Holocaust Project, Donald and I, this came up a lot. Not actually from survivors, that’s the interesting thing, it came up mostly from scholars, academics, who had decided that the Holocaust was beyond comprehension and couldn’t be represented in art. Okay?

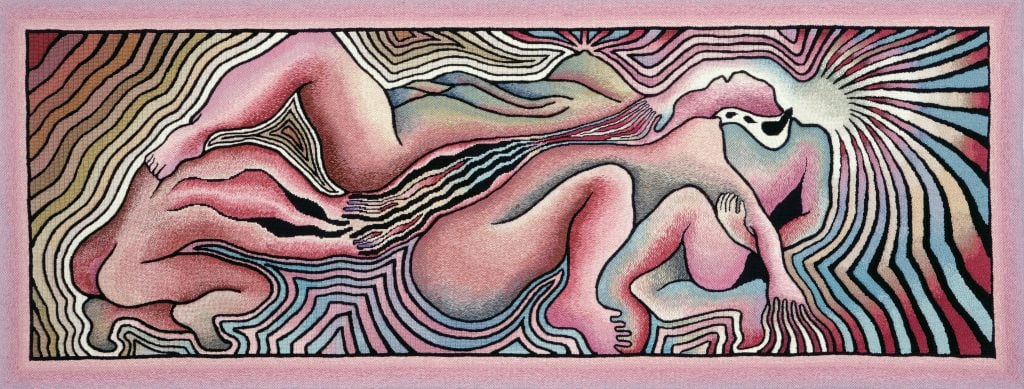

Judy Chicago Birth Trinity: Needlepoint 1 from Birth Project (1983). © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Photo courtesy of Through the Flower Archives Collection of The Gusford Collection.

Okay…

And, it’s true, Donald and I were not children of survivors, but we made a journey, a long journey into the darkness of the Holocaust, using our ability to empathize with the human experience. I did the same thing in The Birth Project.

Now there, I did get questions like, “How can you use images of birth when you never had children?”’ and I would say, “Well my mother had two children, she went to the hospital, she was anesthetized, she went to sleep, she woke up, and she had a baby. What kind of experience was that that would qualify her to make art?”

I, on the other hand, have studied the art of birth going back in time, There is actually quite a bit of art on the subject of birth and maternity, which I discovered in Massimiliano Gioni’s show that he did called “The Great Mother.”

It reminds me, too, that aside from humans and women, you’ve had empathy in your work for animals and for all creatures.

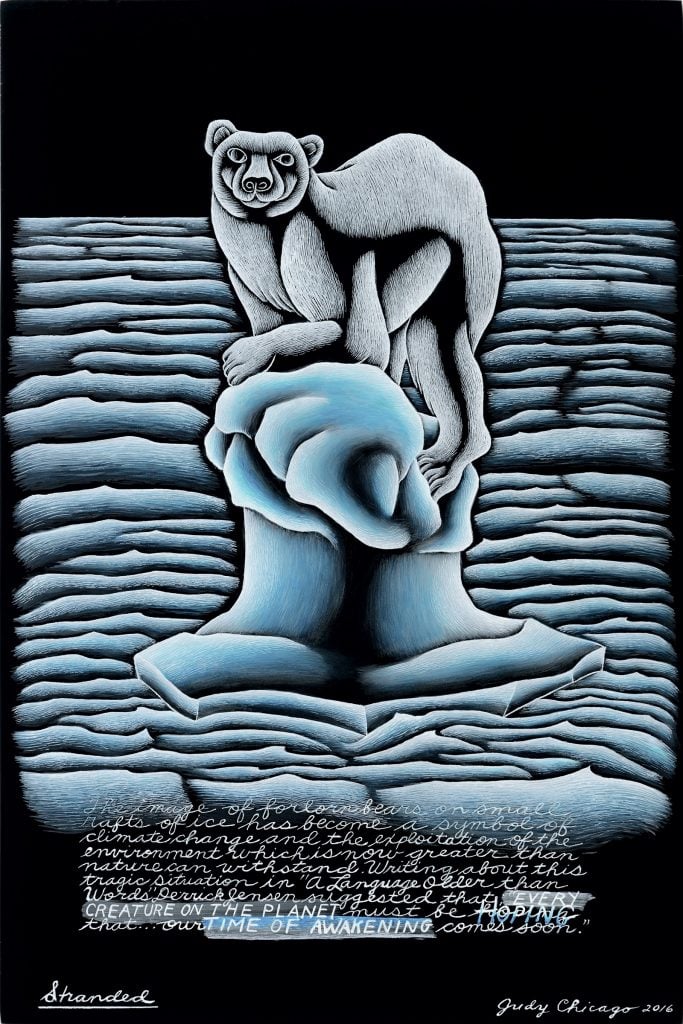

All living creatures, right. See, I believe, actually, that feminism has grown in terms of our concept of intersectionality and the overlap of multiple identities, and I think it has to grow to encompass all living creatures. And if we really believe that every voice counts and that all life is sacred—I mean actual life—then it’s important for us to extend our capacity to empathize.

This will be in the de Young show—my last project, “The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction,” when I got to the extinction part, which took me two years, I have to say, even harder than The Holocaust Project, which was grueling. Because it wasn’t just what we’re doing to other creatures, it’s the scale.

For example, sharks. The finning of sharks for shark fin soup—when sharks are finned alive and after they’re finned they can’t swim, they can’t hunt, they sink to the bottom of the sea where they suffocate to death. And this is done to a hundred million sharks a year.

I was just reading an article today saying that sharks are incredibly important for the entire ocean’s ecosystem.

Every living creature is a part of our complex and awe-inspiring ecosystem.

Judy Chicago, Stranded (2016). © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo © Donald Woodman/ARS, NY.

Part of this Empathy Project is talking about what you’ve done right throughout the last year. What have you done to maintain creativity?

I’ve lived on the fringes of towns and cities for most of my career because of the quiet and the isolation. So that hasn’t been so different. It’s no traveling, that’s been quite different. And at first, I felt guilty about it because so many people were suffering. I was glad for the quiet because I had to finish The Flowering, and I would never have been able to do that if I had been traveling around. In addition to finishing that, I’ve done two series.

One is a series called Garden Smokes which is a series of prints all about containment, confinement. When the pandemic started, I thought back to my early days of doing smoke pieces and just going out with my friends, and I thought, “Oh well, that’d be fun, you know—get out. We’ll go out to different sites in New Mexico and just light smoke.” Then, no, you couldn’t do it because you couldn’t do anything on private land without a permit, all public land was closed off, so I decided to do them in our gardens. In the old days, it was haphazard, the photography, but now that I’m married to this incredible photographer the quality of the images is really startling. It’s wonderful.

The Garden Smokes will probably be up in New York when I do my book launch talk with Gloria Steinem on September 27 at the new Salon 94 space. Life on Pause, I don’t know what I’m going to do, and I’m not quite finished with them yet. They’re slow, they’re paint on porcelain, multi-fired paint on porcelain.

It sounds like the silence and the stability, in a way, of staying in one place ended up actually fueling a lot of your creativity.

I don’t know if it fueled my creativity, but it gave me time! Uninterrupted studio time.

It seems like you can find a space for it wherever you are, and especially now that you’ve been home.

I know, I’ve read about artists who can’t get to their studio, or they have assistants and they can’t get their assistants so they can’t make any art. But I don’t have a lot of assistants. I’m still like, [holds up palm] my hand.

Judy Chicago, Purple Atmosphere (1969). © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo courtesy of Through the Flower Archives; Courtesy of the artist; Salon 94, New York; Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco ; and Jeffrey Deitch Gallery, Los Angeles.

Do you feel that expanding access and creating new connections to art beyond physically touring a gallery or attending a live presentation is an essential step for the industry as a whole?

Oh absolutely. Since Jordan Schnitzer entered our life—Jordan is passionate about bringing art to a broad and diverse audience. He does all these traveling exhibitions from his collection that he makes available free to the venues. All they pay is shipping. And then he also brings a huge amount of educational ancillary programming. I didn’t actually understand this about him until we started working together on this project.

So this is a very good example of a model for how I think art needs to interact with the community. So, because of COVID restrictions, not that many people will be able to actually be on site to see my piece, so we’re live streaming it all over the Coachella Valley and all over the world. He has the resources to do that because he wants my piece to act in a way as a celebration of life after a really difficult period now that we’re at the beginning of opening up.

Donald and I also worked with an organization in Germany called Light Art Space to do a virtual smoke sculpture, an app, that’s free. All you have to do is go on Rainbow AR and you can make a little smoke sculpture in your own apartment. And the kids will be introduced to ecological issues, they’ll be turned onto the app, and then they’ll be able to make their own smoke sculpture and do videos and photographs of that. And that’s going to impact 1,200 kids, 500 teachers in California, and then a whole other educational curriculum in relationship to the Nevada Museum and what they’re doing around my archive.

One of the things I did right away was reach out to the [Native American] tribes and asked for their blessing on my piece. I tried to make it clear that my approach to the land is consistent with their traditional valuing of the land. So, we have, all of us, have tried to be in service to the larger community. And that’s a very different—I told you, I have a very different vision of art. I’m very against the plop the piece down and screw you attitude. It’s just a very different way of trying to bring art into the world.