The Hammer

Simon de Pury on What 50 Years of Watching Industry Tastes Evolve Has Taught Him About Investing in Art

The veteran auctioneer reflects on why art is a solid investment—even as tastes shift faster than ever.

The veteran auctioneer reflects on why art is a solid investment—even as tastes shift faster than ever.

Simon de Pury

Every month in The Hammer, art-industry veteran Simon de Pury lifts the curtain on his life as the ultimate art-world insider, his brushes with celebrity, and his invaluable insight into the inner workings of the art market.

Ever since I started working as a greenhorn in the art world 50 years ago, I have witnessed the art market expand. It has done so geographically, in numbers of participants, and most of all in the level of prices achieved—at the top end and overall. Occasionally, notably in the early 1990s and for a very short time in 2008, there was a temporary slowdown but in absolute terms the market has gone up and up. I expect us to see in a not-too-distant future price levels achieved that none of us ever imagined would be possible. The first ever billion-dollar artwork sale may not be that far off. Documentary evidence on what prices were being paid for artworks go back to at least the mid-19th century, and also demonstrate a near continuous overall upwards trend.

There has forever been this conversation about so-called “pure” good collectors, and the “evil” speculators. Even in my early days I never encountered a collector showing me a work saying, “Look I bought this for x and now it’s only worth a fraction of that price.” Once you start spending a meaningful part of your financial resources on art, it’s only natural that you would want to make sure it is well invested. Seeing the prices go up for what you bought is gratifying as you see it as a validation for your outstanding eye and your shrewd business sense.

Bearing in mind the continuous growth of the art market, it would seem foolproof to invest in it successfully. You would only need to acquire an artwork and sit on it as long as possible. The one thing that interferes with this supposition, at times quite dramatically, is the evolution of taste and availability of top quality works on the market. Up until the late 1950s Old Master paintings represented financially the lion’s share of the art market. Gradually most of the masterworks ended up in public collections and became therefore lost to the market. So even if you had theoretically unlimited funds at your disposal, you could no longer build the best collection of Old Masters. When J. Paul Getty died, he left the bulk of his fortune to the J. Paul Getty Foundation. While they have over the years since acquired an impressive number of outstanding works, it simply is no longer possible for them to catch up with institutions such as the Louvre, the Hermitage, the National Gallery or the Metropolitan Museum.

16th October 1958: Bidders and auctioneers at a Sotheby’s auction of New York millionaire Jacob Goldschmidt’s collection of impressionist paintings. Photo by Keystone/Getty Images.

The gradual “drying up” of top works by Old Masters opened the window for Impressionist and Modern art. With it changed the general taste. A super rich collector no longer wanted to live surrounded with the finest Old Masters and with Italian renaissance furniture but with the very best Impressionists and post-Impressionists. The most coveted decorative arts to go with it were French ormolu mounted 18th century furniture, silver, and porcelain. The auctions that Sotheby’s staged in Monaco in the 1970s with works from the Rothschild, Rédé, Béhague, Wildenstein or Ojieh collections catered to that taste. No wonder their evening auctions were a magnet for tycoons of the period. The 1980s saw the impact of strong Japanese buying pushing the price levels for Impressionists and post-Impressionists ever higher. This culminated in May 1990 when Ryoei Saito bought within 24 hours Portrait of Dr. Gachet by Vincent van Gogh at Christie’s for $82 million and Le Moulin de la Galette by Pierre-Auguste Renoir at Sotheby’s for $78 million.

Sotheby’s and Christie’s started organizing contemporary art sales in the early 1970s. It was then regarded as a novel side category that was insignificant in financial terms. Looking at some of the early catalogues is a fascinating object lesson in the change of taste. There were full-page illustrations for works by photorealist (or hyperrealist as they were then called) artists who today with the exception of Richard Estes or Malcolm Morley have returned to complete oblivion. Paintings by artists that are worshipped today, such as Cy Twombly, were only illustrated in tiny postage stamp sized format.

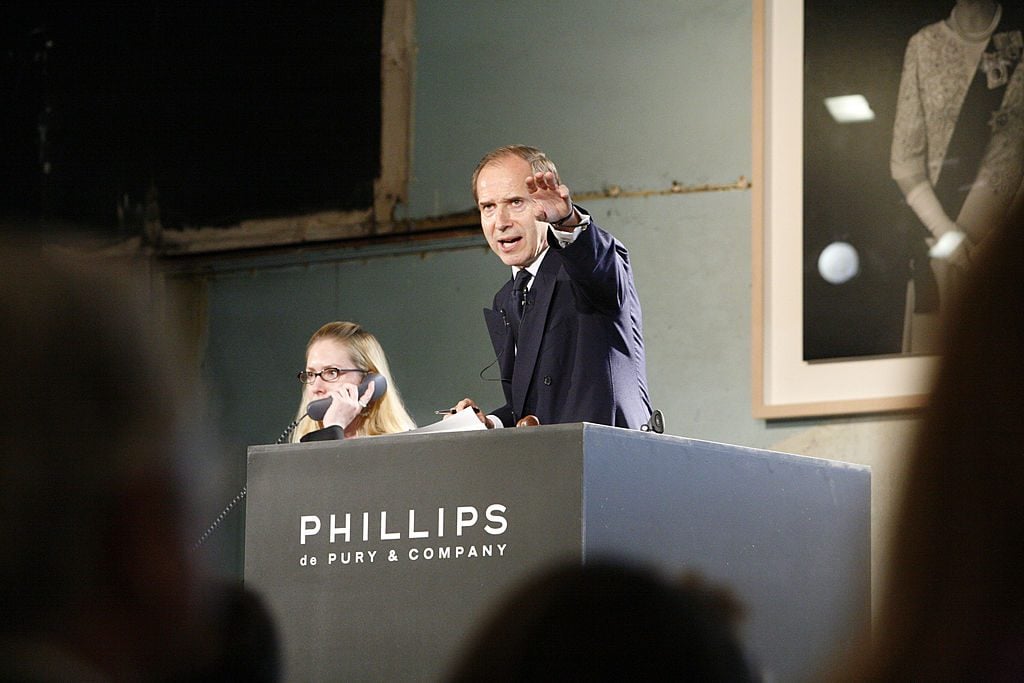

Early in the 21st century, contemporary art sales were becoming bigger and bigger and financially more and more significant. The category was being divided into postwar and contemporary art, and eventually dethroned Impressionist and Modern art to become the most lucrative part of the global art market. When I became majority shareholder of Phillips de Pury and Company in 2003, we decided with my colleagues to focus entirely on very recent contemporary art, design, and photography. Every season we would decide together which artists, designers and photographers whose works had never appeared at auction before, to introduce into our sales.

We were championing works by Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, Robert Gober, Cindy Sherman, Christopher Wool or Richard Prince, as well as Helmut Newton, Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth and Thomas Ruff, or Ron Arad, Marc Newson and Zaha Hadid. The long list of artists that we were the first to sell, from Mark Bradford to Mark Grotjahn, from Ai Weiwei to Mickalene Thomas, from Urs Fischer to Elizabeth Peyton, is what I am proudest of when looking back on this period. It was gratifying to see that a large chunk of artists that we either championed or introduced in day sales during the 2000s became top artists in the evening sales of the three main houses during the 2010s. In such, we became tastemakers for the secondary market. If today’s high-net-worth individual prefers to be surrounded by cutting-edge contemporary art and by French furniture by Royère or Prouvé, we did play our part in this.

Simon de Pury during Phillips de Pury and Company – 210th Anniversary Party and Auction at Howick Place in London, United Kingdom. Photo by Richard Lewis/WireImage for Phillips de Pury & Company.

The only category that is up to a degree immune to changes in taste are the ultimate “trophies” that are so exceptional and rare in quality that anyone able or prepared to spend more than $100 million on a single artwork cannot afford not to go after them, if and when such works become available. Nearly everything else will be affected by the evolution of taste. Most of the 18th-century French furniture that was being hotly pursued by the super rich in the ‘70s is worth only a fraction of what it was back then. Renoir, who was a hot commodity in the ‘80s, has—unless you are speaking of one or two of his seminal works left in private hands—gone down substantially in value. Pocket watches, snuff boxes, Art Nouveau glass, postage stamps, which were all major collecting categories when I started, have gone down significantly. We can safely assume that what we value most highly today will no longer be sought after in the same way 50 years from now.

Change of taste is accelerating. While process-based abstraction was all the rage some five years ago, most current “hot” artists are figurative in a neosurrealist vein. What is in will be out. What is out will not necessarily be in. Nevertheless art as well as other tangible assets will offer some of the best investment opportunities during the turbulent times ahead. The constant evolution of taste has to be closely monitored. In my next column I would like to analyze what are some of the driving factors behind change of taste.

Simon de Pury is the former chairman and chief auctioneer of Phillips de Pury & Company and is a private dealer, art advisor, photographer, and DJ. Instagram: @simondepury