People

‘You’re Going to Have to Deal With Me’: McArthur Binion on How He Kept the Faith in Abstract Painting, Even When It Wasn’t Fashionable

Binion has created a career on his own terms, and is determined to pay it forward.

Binion has created a career on his own terms, and is determined to pay it forward.

Folasade Ologundudu

This article is part of a series of interviews by Folasade Ologundudu exploring the evolving conversation about abstract art among Black artists across different generations.

Born in Macon, Mississippi in 1946 and raised in Detroit, McArthur Binion was the first Black graduate of Cranbrook Academy of Art. In New York in the 1970s, he embarked on a rigorous painting practice. Rooted in minimalism, he quietly honed his craft for decades, finding fame and fortune only later in life.

From 1993 to 2015, Binion taught at Columbia College in Chicago. He only scored gallery representation at the age of 65. Recently, he’s been on a tear, showing widely including at the Venice Biennale in 2017, where his “DNA” series was a highlight.

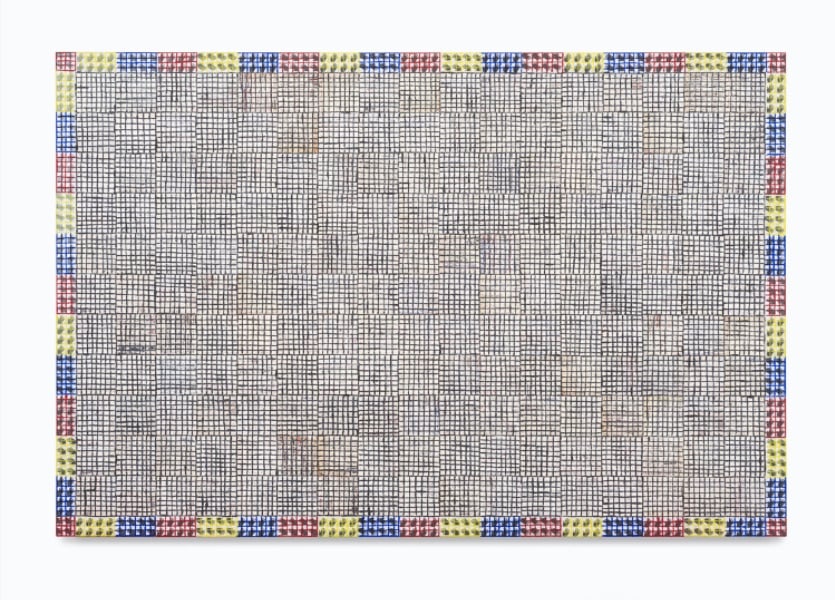

Known for his meticulously hand-drawn “grided” paintings, Binion’s use of photography, text, ink, and oil-paint-sticks reveal a fiercely personal practice. Immersed in color theory, abstraction, and African American history, his most recent show at Lehmann Maupin in Chelsea presented nine challengingly intricate paintings, and marked vivid new direction for his practice.

At 75, Binion is looking towards the future. Committed to leaving a map behind for Black artists to follow, he established the Modern Ancient Brown Foundation in Detroit in 2019. The inaugural three-month residency will offer studio space, stipends, and invaluable critique from Binion and selected guest mentors.

The painting DNA : Study by McArthur Binion during the press preview of the 57th Venice Biennale. Vincenzo Pinto/AFP/Getty Images.

In a recent interview, Binion shared with me his ambitious plan to leave a roadmap behind for the next generation of Black artists and the ways in which the history of abstraction—and, indeed, Modernism—needs to be rewritten to recognize the ingenuity of Black artistic contributions to the art form.

What are some of your earliest memories coming in contact with art? What are some of the personal experiences in your life that led you into the art world?

I didn’t have any early experiences with art. The first time I went to a museum, the Museum of Modern Art, I was 19 years old. I didn’t come from a family of artists. I met a man, Charles McGee, and he was the first artist I ever met, a Black man from Detroit. I didn’t see any of his work, I just knew he was an artist, and he had these really groovy parties. I started out as a writer at school. Then, after dropping out of school, traveling to Europe, and moving to New York when I was a kid, I discovered I was painter.

I had a stutter in high school as a kid, but at the same time I was the most popular person in my class. That experience was about nonverbal communication, and therefore painting. And it took me a long time to figure out how to make art because I had never drawn. I was 19 when I came to New York, and I took my first drawing class two years later.

What prompted you to take an art class? What were you interested in?

When I went to the Modern, I was deeply influenced. I’d seen paintings for the first time. I never thought of painting as a philosophical pursuit. I dropped out of school when I was 21 and went to Europe. I was always hanging out with cool people. Most of my friends were art students and music students and they would say to me “you should take an art class because your writing is really special.”

Fortunately, I just listened to my body, and I took a class. I drew 40 hours a week for two years. I wanted it because I was so bad at it. And the point I want to make to you is that because I arrived from this alternative group—like not knowing about art—I was able to introduce things that someone who’d been trained could never reach. I was trained to draw in a classic way but all along I had a desire to be an abstract artist because I was very involved with really high-level jazz musicians, like Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor.

Installation view of “McArthur Binion: Modern:Ancient:Brown” at Lehmann Maupin. Photo by Daniel Kukla. Courtesy of Lehmann Maupin.

So you’re in this drawing class. This is college. You’re 22. The students that you’re in class with are 18. They’ve been drawing all their lives. You’ve come in and you’re brand new. You have references from the music world because you were doing music production and you come to abstraction through jazz?

No, we come from the same place. Me and jazz come from the same place. We recognize each other.

In the ‘40s, the New York artists were basically doing Cubist work. They were Picasso freaks. And then they moved from that to pure abstraction really fast. How’d they do it?

They went around the corner to the major jazz clubs in town and listened to bebop music artists who taught them improvisation and abstraction. Now, they never talk about that, because if they talk about that they have to reorder the world. They have to put us, the Black artists, on top.

I didn’t really get into abstraction until graduate school. And the whole time I’m here just checking the whole thing out, I’m quietly super super competitive. I came here to kick some ass. I was a kid in New York hanging out with major artists and amazing musicians and I was very comfortable in that because I’m a natural born hustler.

I’m interested to know what about abstraction appeals to you—not now, but then?

Abstraction is my life. Just by looking at who I am, I was never normal. For me it’s about how I see the world. Art isn’t about logic it’s about feeling and back then there was no social media. You’re receiving information live or at a gallery. I knew where I wanted to go, quality-wise. There was a certain level of quality I wanted to achieve in order to communicate what I was sharing.

Installation view of “McArthur Binion: Modern:Ancient:Brown” at Lehmann Maupin. Photo by Daniel Kukla. Courtesy of Lehmann Maupin.

I want to talk about New York in the ‘70s. I’d like to hear you speak about the magic of New York in those years.

New York was really good in those years. It was a place where you could have a part-time job and be a full-time artist. What happened in the ‘70s is that all the Black people, we had to come together because the art world was white and they weren’t letting any of us in.

What they did was they gave the major artists cushy teaching jobs. That was the ceiling of academia. Jayne Cortez, a friend of mine and a Black poet, wanted me to keep teaching—but I quit that. One school wanted to offer me tenure and I quit. The ‘70s were fucking amazing. You could feel the energy in the streets, and everybody knew each other because we all hung out at the same jazz clubs.

So there was always a deep connection between the art and the music?

Oh yeah. I wasn’t friends with artists. I was friends with poets and musicians, because painters were basically boring.

For me, when someone is like, “I was I showing in galleries in the ‘80s?”—I turned down all the major galleries! I always knew if you didn’t get it on your own, someone else controls it. I didn’t work with any galleries. My first gallery was when I was 65 years old.

Installation view of “McArthur Binion: Modern:Ancient:Brown” at Lehmann Maupin. Photo by Daniel Kukla. Courtesy of Lehmann Maupin.

So you sold your own work?

In those days you could get on an airplane with multiple portfolios and no one blinked an eye. I would make house calls. I could get on airplanes with multiple portfolios and go to cities in the midwest. I sold work to some collectors but also to school teachers and factory workers. My rent for a big ole studio was like $350 a month in New York, right in Chelsea. So I would go and I would make enough for six months.

Who are a few artists, writers, filmmakers, and critical thinkers who have inspired you in your lifetime and why?

The people that have inspired me are James Baldwin, LeRoi Jones, who became Amiri Baraka, Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, Archie Shepp—I can keep naming names, but these were just amazing artists and people. The people I gravitate towards are people that made themselves. I didn’t come from art history, I landed there. You don’t come from Macon, Mississippi and all of a sudden make art. The friends I have who are still here, who are still alive, we all have this faith in each other. We had high expectations of each other.

![McArthur Binion, <em> Modern:Ancient:Brown</em> (2021) [dteail]. Image courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2021/12/mcarthur-binion-detail.jpg)

McArthur Binion, Modern:Ancient:Brown (2021) [dteail]. Image courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin.

Stanley Whitney, David Hammons, Dianne McIntyre. Jack Whitten—who died a couple years ago—Howardena Pindell, Candace Hill-Montgomery, Charles Gaines, Todd Gray. You have to understand, those were amazing times. We were all working, and we expected a lot from each other.

What do you think about the younger generation of Black artists working today?

Young artists today are becoming more a part of the mainstream. We need second and third generation artists.

Up until the late ‘90s some of the best Black minds went into law school, business school, or medical school. People slowly learned that you could make that kind of living or better being an artist. So now, some of the best minds are going into art.

You told me earlier that you’ve been working in the same way since the ‘70s. I’m fascinated about the idea of doing something for 30-plus years. How has continuing to work in the same way impacted the nature of your work and how have you evolved over the last 30 to 40 years? What have you learned about yourself through this methodology?

For me, constancy is really important. I’ve matured. I’ve refined who I am in terms of how I approach my work, but it’s the same intuition, the same notions I’ve had since I was 19.

It’s just getting to the point where you totally respect the quality of your own work. It’s not so much about refining; it’s getting yourself in a position where you leave a map for the younger Black artist. For me and my work—there’s no language for it. That’s what I’m after. That’s why I say I landed in art history. I’m not from there. I come from picking cotton at three years old.

McArthur Binion, Hand:Work (2019). Image courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin.

In your opinion, do Black abstract artists have more freedom in their work than Black figurative artists, whether those are painters or sculptors?

Most people do not understand the rigor of abstraction. It’s hard. To make the abstraction personal, that’s the deal. That’s when you’ve arrived. You’ve arrived when you can pull that off. It’s all hard, but it’s much easier to make figurative work.

Can you talk to me about the works in your newest and fourth solo show at Lehmann Maupin. What are themes, ideas, and concepts you’re working through in this work?

It’s the culmination of my “DNA” work, which I developed slowly over years. This is the logical conclusion of the work. I admitted to myself that I wasn’t bringing my full power as a painter into my work. I kept asking myself, “what’s missing?” and I’m getting into that here. In terms of color, the most I would use would be two colors before. Now I use eight. I want to bring them in because, like I said before, I want to leave a map. And this is kind of new for me, sharing. Because I want you guys in the end to understand me and I want to leave a map.

![McArthur Binion, <em> Hand:Work</em> (2019) [detail]. Image courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2021/12/mcarthur-binion-detail-1.jpg)

McArthur Binion, Hand:Work (2019) [detail]. Image courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin.

Because I’ve built something I believe is really strong and really good and I don’t want it go away like they do with most Black artists. You’re going to have to deal with me. I’m going to fight to the end. Plus, I want to go to the top and if I go to the top I can bring more of us with me. I’m in it for the race.

One more thing: We didn’t get the credit for Modernism. Modernism is formed on the back of African sculpture—I mean, Picasso?

That’s essentially the foundation of contemporary art.

That’s what I’m saying. When I’m gone, they’re going to say, “this motherfucker here, we’ve got to deal with him.” I mean, I know the white people, I know the Black people, and I’ve always been able to move between those two easily as I have for all of my career.

It’s so important to be able to move in rooms with all kinds of people.

Absolutely—but at the same time keeping the Black room full. I think I’m starting that with my foundation.

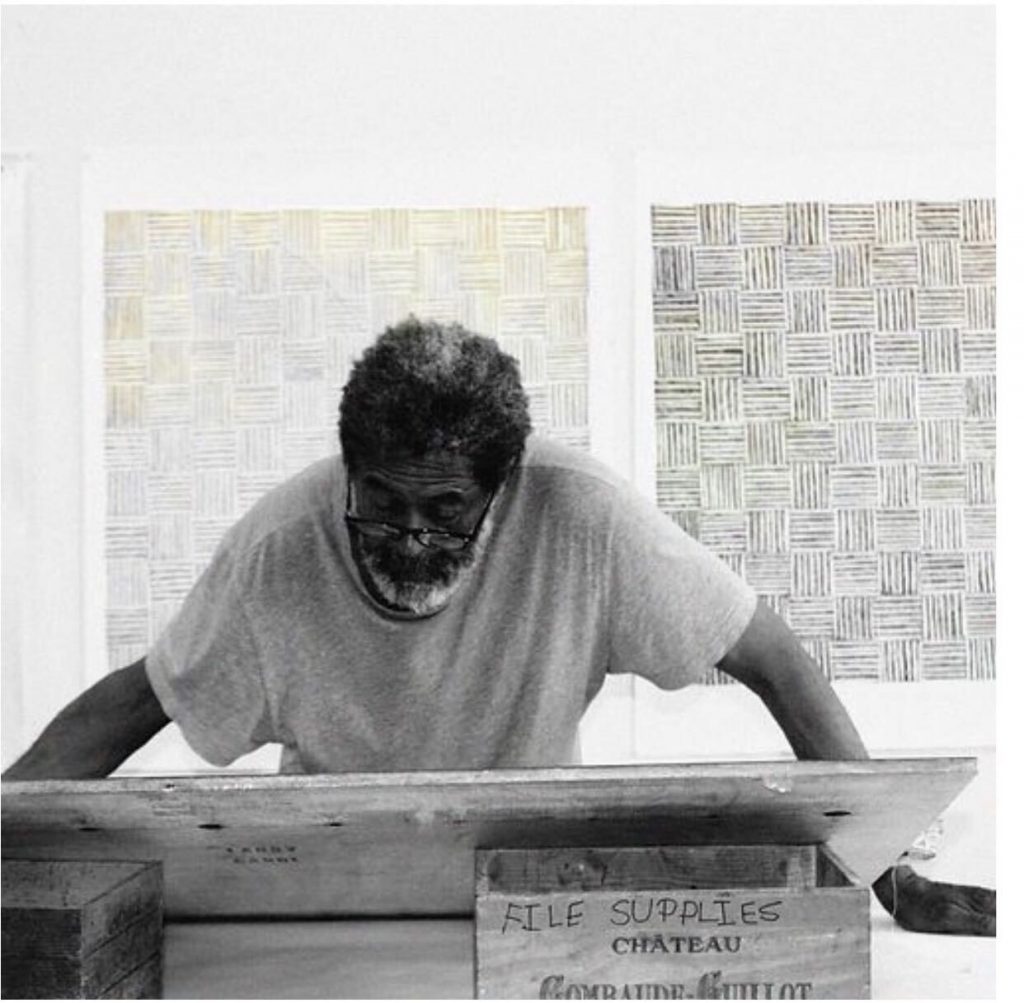

McArthur Binion in his Detroit studio, where the Modern Ancient Brown residency will be held. Image courtesy Modern Ancient Brown Foundation.

When did you start your foundation?

Almost three years ago. I stopped teaching six years ago. And it took me about three years to figure out what I wanted to do. My daughter really affected how I wanted to give back. She was like, “Why would you leave all this money and never give anything back?”

So I focused on Detroit. A couple weeks ago I did a two-day seminar critique of nine local Detroit artists that applied to this grant through the foundation. I bought a really nice studio for the visual arts. It’s a space for about three artists. They get three months in a year plus $500 a month to dive into their practice or for living.

The word of mouth is huge. I’m eventually going to take the top nine or seven, put them on my back, and show with them in regional small museums in the midwest. The goal is that in five years all these will be full-time working artists.