Artnet News Pro

Smart Contracts Are Artists’ Best Weapon in the Fight Against Flippers. Here’s How They Work

Here is everything you need to know to understand smart contracts—and how they can make the market more equitable.

Here is everything you need to know to understand smart contracts—and how they can make the market more equitable.

Tim Schneider

A version of this article originally appeared in the Artnet News Pro fall 2022 Intelligence Report.

You want to buy a new painting from a midsize gallery? It’s not as simple as it sounds.

After you pay the PDF invoice, you’ll need to remember to save it in a folder you won’t forget about, because the invoice and your proof of payment act as your legal title to the painting. If the gallery includes a certificate of authenticity to memorialize the sale, that document too becomes your responsibility to maintain; worse, it might not even guarantee the piece is legit without separate confirmation that it came directly from the artist’s studio. If you later decide to sell the painting without the gallery’s or the studio’s involvement (whether or not doing so violates any resale covenants in the original invoice), both entities might lose track of the work for good, reducing its odds of inclusion in museum exhibitions or an eventual catalogue raisonné.

Does any of this seem desirable for anyone involved?

As it turns out, there is another way. Imagine that you could pay for the painting and immediately receive separate digital proof of title through a verified, super-secure database that you, the gallery, and the artist bear no responsibility to maintain yourselves. What if the chain of title also automatically updated every time the painting changed hands afterward, regardless of what you or later resellers communicated to anyone outside the deal? And what if you knew that breaching any resale covenants governing your original acquisition would remotely trigger immediate enforcement measures—or that stewarding the painting long-term could generate surprise bonuses from the gallery or the artist?

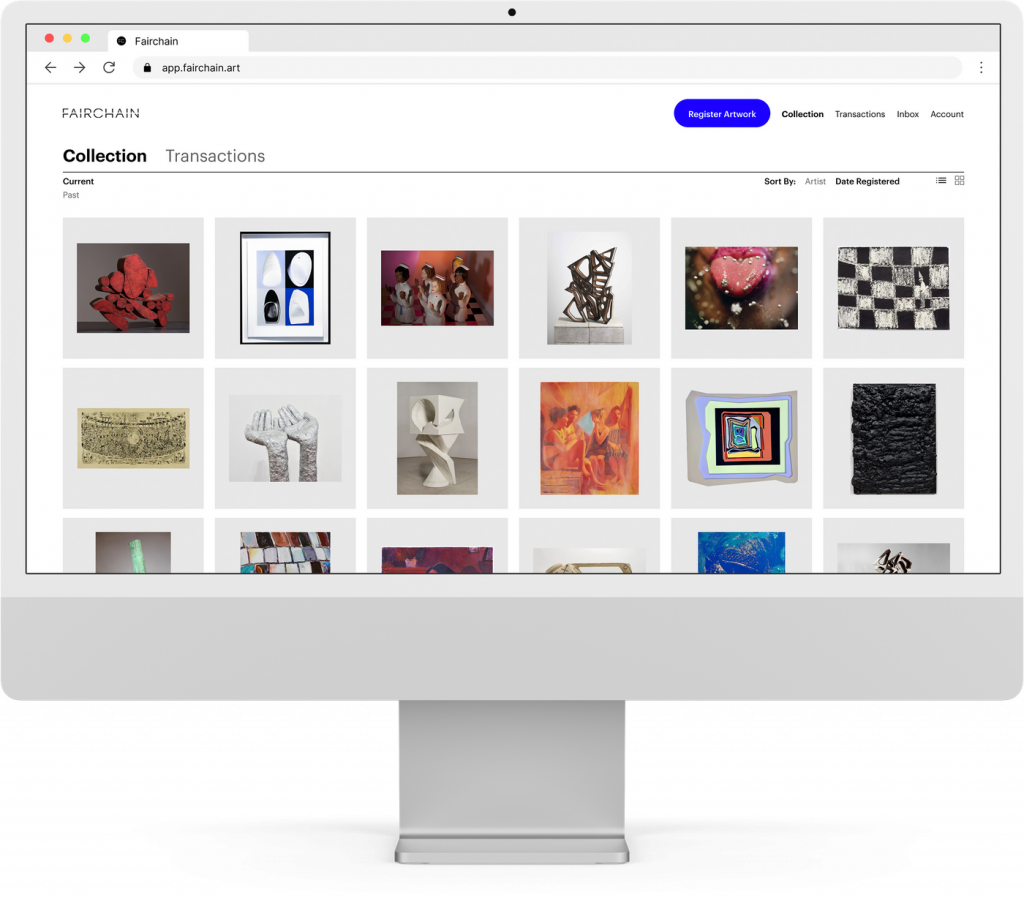

The interface on Fairchain. Courtesy of Fairchain.

Every upgrade in this second scenario is now possible, thanks to smart contracts—algorithms digitally coded to self-execute and self-document on the blockchain. No other recent tech product could strengthen the hand of artists and dealers so quickly or so aggressively.

Smart contracts have already sent shock waves through the banking and lending industries. Rather than try to work with institutions that hold the power to deny, delay, or charge fees to carry out desired transactions, a growing number of customers have begun leveraging the blockchain for peer-to-peer labor arrangements, loans, and insurance via smart contracts. Blockchain software developer ConSensys estimated that this subsector of the economy, known as DeFi (short for “decentralized finance”), generated more than $120 billion worth of business in March 2022, even as the cryptocurrency market leaned into an extended swoon.

As a growing number of art-market players begin to circle smart contracts, exactly what they can do—and why the industry should care—remains shadowy to most. Allow us to break it down.

Below, we describe three epiphanies the art industry needs to have in order to truly embrace smart contracts. Then, we offer three practical ways smart contracts could shift the status quo away from the speculators who have driven so much art-market activity in the 21st century and back toward the creators.

A central irony here is that experts on all sides of the issue agree that smart contracts are neither particularly “smart” nor even genuinely contracts at this point.

On their own, smart contracts can automate only transactions rudimentary enough to be reduced to “if–then” instructions with objective triggers that can be described in a programming language. Most of the human complexities of a true contract (for example, a commitment that one party will “take all reasonable steps” to accomplish a mutually desired outcome) are incompatible with this requirement.

In fact, most judges would say that smart contracts cannot even contain the necessary ingredients of a deal; they can execute an outcome only once the bargaining is over. “In a legal sense, a contract means two people agreeing,” said Louise Carron, an associate at Klaris Law specializing in intellectual property at its nexus with new technology. “If you look at smart contracts as lines of code, that’s not where the agreement between parties is.”

These limitations make it difficult for the tech to ever be much more than a vehicle for the automated transfer of money, property, or assets. Case in point: in the U.S., only a handful of states have so far passed legislation recognizing these packages of code as enforceable in court.

Although smart contracts work best when supplemented by traditional contracts, they still bring new value. “One benefit is the ubiquity, transparency, and relative permanence of blockchain,” said Kevin McCoy, the artist, NFT coinventor, and cofounder of NFT-services platform Monegraph.

Smart sales contracts for art (physical or digital) live in collectors’ crypto wallets, whose contents can be viewed publicly using free software. By jointly maintaining the database, the many computers making up every blockchain network also ensure there is no single point of failure for critical details about artworks and their ownership history.

Given the art world’s typical techno-hesitance and the current state of tokenization, smart contracts for physical artworks face an uphill battle for adoption. But the rest of the trade would suffer an immediate reckoning if a critical mass of the people making the work that so many others are desperate to buy simply said, “The only way to acquire anything of ours is by using digital contracts.” The question is whether the makers are cognizant of their own might—and ready to wield it for this cause.

“Until artists recognize that they have more power and influence than they realize, things won’t change,” said Max Kendrick, cofounder of Fairchain, a platform that uses blockchain-backed records to authenticate, track title to, and facilitate sales of art. “However, that realization is starting to take shape.”

The team at Fairchain. Courtesy Fairchain.

Fairchain is evidence of the shift. Its advisors include established artists Hank Willis Thomas and Laurie Simmons, while it counts Carroll Dunham, Alteronce Gumby, and rising star Ludovic Nkoth as investors. Dealers are coming around, too: New York-based Hannah Traore is another investor, and fellow Gotham galleries David Lewis, 56 Henry, Sargent’s Daughters, and Charles Moffett will soon hold shows where works can be acquired via Fairchain’s services. (Kendrick stressed that, in contrast to most other smart-contract algorithms, the company’s blockchain-based agreements are supplemented by traditional contracts that are digitally signed by all parties.)

There is a key obstacle to the art trade’s adoption of smart contracts. Within crypto circles, it is most commonly known as “the oracle problem,” but it is also sometimes called the blockchain air gap. Both terms describe the impossibility of flawlessly linking a blockchain-based asset like a smart contract to an external asset like a painting. (Smart contracts are only usable for an off-chain asset once it has been tokenized, meaning documented with an entry on the blockchain.)

A number of startups claim to offer solutions, such as shooting high-resolution photographs of prescribed slivers of artworks, then linking to them from the associated smart contracts’ metadata for later cross-checking against the purported real thing. But critics say the current options are insufficient to prevent forgers, looters, or scammers from taking advantage.

Frank Stella, Geometry XXII (2022). Courtesy of Arsnl.

Nanne Dekking, founder and CEO of blockchain-powered artwork-title registry Artory, admits that existing methods for closing the blockchain air gap are “not there yet.” But he also contends that bad actors are likely to regard the mere existence of a professionally vetted, shared digital record of provenance as a red line not worth crossing when it comes to unique objects.

“If a work is registered on the blockchain, the chances that someone will create a forgery of it become very low,” said Dekking. To analogize: Why risk robbing a house with a security system sign out front when there are so many others without one?

Air gaps are not exclusive to digital technology. Significant ones already exist between physical artworks and the most prized forms of traditional record keeping: invoices, certificates of authenticity, catalogue raisonné entries, inventory-management software. Even if their information is accurate and current, each of these items can be forged, corrupted, destroyed, improperly updated, or simply lost over time.

Well-designed smart contracts are more secure, more trustworthy, and more complete than all of the above. The reason goes beyond the security measures and redundancies built into every blockchain network. When used for sales, smart contracts also automatically update ownership details for all parties in the transaction. This means that artists and their representatives always have comprehensive provenance and that buyers always have clean proof of title tracing all the way back to the studio—without, say, anyone’s overburdened assistant having to manually make changes in a shared Google Doc or one-sided inventory-management database.

Artists and dealers have long tried to combat speculators by writing resale covenants into traditional contracts. Most often, these covenants hold buyers liable for monetary damages if they flip a work either before a designated holding period expires or without granting the gallery right of first refusal. The problem? Enforcing these covenants requires first finding out that the buyer is in violation, then bringing an expensive, time-consuming lawsuit that generally cannot even recover the artwork should it succeed.

Smart contracts could do much more. McCoy suggested they could be coded with a “clawback clause” that automatically returns the digital title to the artist’s crypto wallet if, say, a buyer tries to transfer a work to someone else before the specified holding period ends. Hard-coding veto rights is another possibility; this wrinkle would make it impossible to transfer the smart contract (and, thus, on-chain title) to another party without electronically notifying the studio or gallery, which could then block the transaction with one click.

A physical artwork could still be sold without its on-chain title, of course. But any such sale would be fraudulent by default, with the smoking-gun evidence sitting right there on the blockchain for all to see.

If you’ve heard anything about using smart contracts for physical art sales, it’s that they can embed an automatic resale royalty to the artist. Every work sold through Fairchain, for instance, can transfer a royalty for the creator immediately upon payment of the purchase price. Arsnl, the Artists Rights Society’s in-house NFT platform, even wrote smart contracts that prevent Frank Stella’s “Geometries” NFTs from being resold on an exchange that refuses to pay resale royalties to creators.

While this prospect is an incentive for artists to use smart contracts, it has for decades been seen as a deterrent to buyers. (Artist Seth Siegelaub and attorney Robert Projansky wrote a similar clause into their analog Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer and Sales Agreement in the 1970s; it never really caught on despite being made freely available.)

What is seldom discussed, however, is that smart contracts could also facilitate tangible rewards for buyers. Since the execution of every smart contract is timestamped on the blockchain, the metadata could be coded to, say, airdrop an NFT or other exclusive digital content by the artist to any buyer of a blockchain-backed physical artwork who holds it for a certain time period. Studios or galleries could also maintain these kinds of “loyalty programs” by manually checking the contents of clients’ crypto wallets, then sending out rewards. The smart contract doesn’t just need to be the stick—it can also be a carrot.

Installation view, “Snowfro: Chromie Squiggles” at Venus Over Manhattan.

Even optimists recognize that there are obstacles to the wide adoption of smart contracts in the art trade. While coding and deploying smart contracts is something that artists or dealers could do themselves in theory, the complexity of the process means that “in practice, only blockchain developers are doing it,” McCoy said.

At the moment, the industry can realistically integrate smart contracts with physical works only through specialized intermediaries like Fairchain, Artory, or Art Basel and the Luma Foundation’s new enterprise, Arcual. But that may change as asset tokenization gathers momentum across the finance, video-gaming, music, and publishing industries.

The past several decades have seen successful artists accumulate more money, business autonomy, and social influence than ever before. If enough of them decide to leverage some of their nascent power to standardize the use of smart contracts for greater control of their physical artworks, no one could stand in their way.

The technology’s fate in the art market will be determined primarily by artists’ interest in one of crypto’s animating principles: self-sovereignty. If the third decade of the 21st century follows the same trajectory as the first two, tokenization of paintings, sculptures, and other tangible works could be the next destination on that trend line.

“It’s not a matter of if but when,” said Kendrick, “and you don’t want to be the last one to board this train.

For more from this issue, download the full Artnet News Pro fall 2022 Intelligence Report here.