Auctions

Sotheby’s Online Contemporary Sale Fetches $13.7 Million—More Than Doubling the Previous Record for a Virtual Art Sale, Set Three Weeks Ago

But the statistics don't account for the high number of withdrawn works.

But the statistics don't account for the high number of withdrawn works.

Eileen Kinsella

Sotheby’s reported a key milestone yesterday when its year-to-date online sales ticked over $100 million, thanks to a $13.7 million online contemporary day sale that opened May 4 and closed May 14. The sale more than doubled the previous record for any online sale by the company—a high mark set three weeks ago by another contemporary auction, which fetched $6.4 million. (Christie’s highest online total is $9.5 million.)

“We’ve held 44 auctions since March 1,” CEO Charles Stewart reminded Artnet News in a recent phone call. The auction house, which began building up digital infrastructure under its previous CEO Tad Smith, put its foot on the gas pedal more forcefully amid the global shutdown.

Stewart, who has an extensive background in finance, took the reins of Sotheby’s in October, roughly four months after the business was acquired for $3.8 billion by telecom magnate Patrick Drahi, and four months before the world began to shelter in place, throwing all markets into disarray. (Stewart previously worked for Drahi at the cable-television company Altice, where he served as CFO.)

Charles F. Stewart, chief executive of Sotheby’s. ©Sotheby’s.

“Of course, there is any number of things changing about how we sell, but we’re adapting and clients are adapting, too,” Stewart said. As part of that adaptation, Sotheby’s has added a “Buy Now” button, eBay style, for certain lots and has focused on expanding its luxury-goods offerings, including weekly watch auctions. Online sales lend themselves, Stewart said, to “things where there are multiple versions of them, such as watches, or jewelry, or wine. You don’t need to see a bottle of wine in the same way you need to see a an Alex Katz painting to fall in love with it.”

But Sotheby’s is pursuing novel strategies on the art side as well. Its record-setting contemporary sale boasted an unusual breakdown: 112 lots sold, five lots unsold, and a hefty 27 lots (roughly 19 percent) withdrawn prior to the close of the sale. Asked about withdrawal options available to consignors—a number of whom were clearly unnerved by the lack of bidding activity on their lots—a representative said, “In an unprecedented period, we were flexible with consignors to best meet their needs and ensure they felt confident bringing their works to auction.”

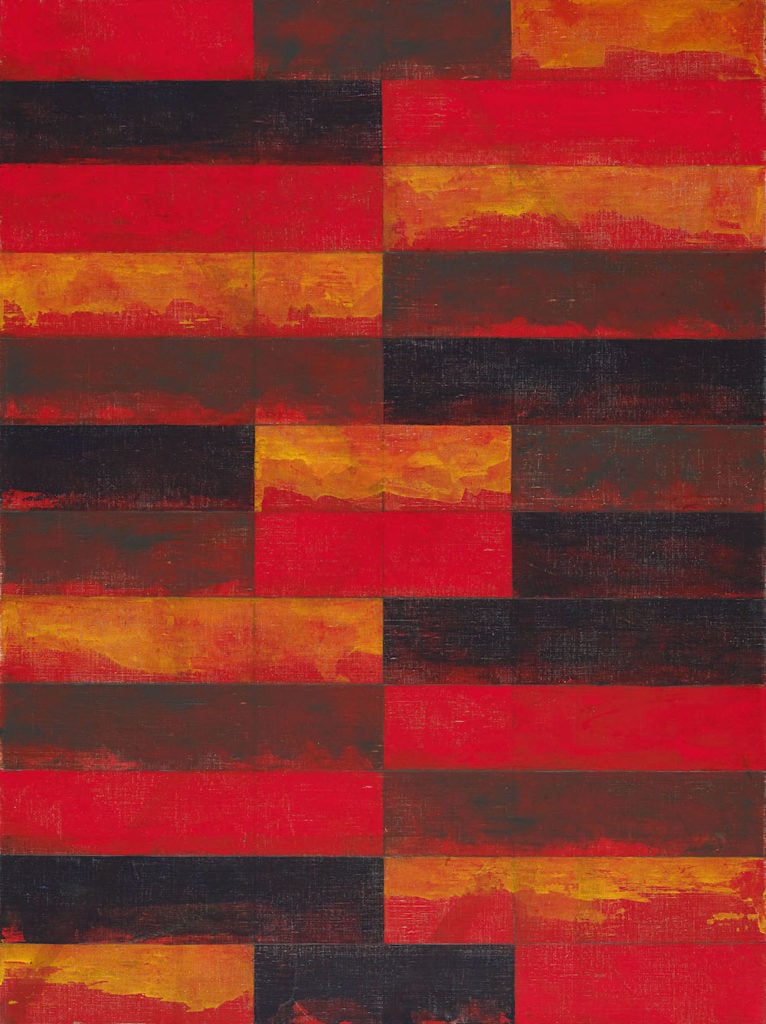

Brice Marden, Window Study #4 (1985). Image courtesy Sotheby’s.

While the option to withdraw a work 10 days into a sale was likely key in enabling Sotheby’s to secure property—and is a keen way to keep the sell-through rate (and market confidence) high—it also creates misleading top-line figures that suggest the $13.7 million total exceeded the high estimate, when it fact it likely would have fallen short if accounting for the many withdrawn lots. (Sotheby’s declined to provide a pre-sale estimate including withdrawn lots.)

Still, the overall result is the highest yet for an online sale—and many of the prices seem to serve as a counterargument to the notion that people are reluctant to spend money on younger, less museum-tested artists during moments of economic uncertainty.

Just two lots—works by Christopher Wool and Brice Marden—broke the million-dollar mark. The Wool was an untitled 1988 abstract painting with a third-party guarantee that squeaked by with one bid to make $1.22 million, just over its low estimate of $1.2 million. (Final prices include the buyer’s premium; pre-sale estimates do not.) The Marden, a 1985 painting titled Window Study #4, fared better, selling for $1.1 million after eight bids and easily clearing the $700,000-to-$900,000 estimate.

Meanwhile, Yoshitomo Nara, whose auction record soared to just under $25 million at a Hong Kong auction last fall, was also in demand. Witching (1999), featuring one of his signature childlike figures with shut eyes and an obstinate expression, sold for $740,000, in the mid-range of the $600,000-to-$900,000 estimate.

The sale kicked off with a lot that generated some controversy in certain contemporary-art circles: a work by Matthew Wong, the much-admired artist who died by suicide in October at the age of 35. A flipper consigned Untitled (2018), a small watercolor on paper, two years after buying it at the artist’s first gallery show in 2018—and just months after his tragic death. And since it is nearly impossible to find work by Wong on the primary market (the paintings in his final show at Karma last year were not for sale), this one was bound to ignite fireworks. The final price was $62,500, four times its $15,000 high estimate, thanks to more than two-dozen bidders.

Lucas Arruda, Untitled (2012). Image courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Other artist records were set for works by Claire Tabouret, Katherine Bradford, and Kengo Takahashi. Nathan With a Purple Hat (2019) by Tabouret, whose in-demand figurative paintings often scrutinize identity, memory, and childhood, leapt over its $35,000 high estimate to a final price of $81,250.

The sale also included plenty of other buzzed-about names that saw solid results, including Lucas Arruda ($350,000 for an impasto-heavy seascape) and Julie Curtiss ($150,000 for a painting of a woman with curlers in her hair). A Jeff Elrod painting once owned by Leonardo DiCaprio, meanwhile, sold for $25,000, just below its low estimate.

Among more established artists, a record was set for hyperrealist painter Richard Estes, whose Broadway and 64th (1984) sold for $860,000 on an estimate of $300,000 to $400,000.

Richard Estes, Broadway and 64th (1984). Image courtesy Sotheby’s.

Max Moore, co-head of the contemporary art day sale, said that bidders came from 35 countries—and, perhaps even more interestingly, 40 percent of bidding came via mobile device.

Asked about the challenges of managing the sale for the first time with no live component, Moore said, “It’s worth noting that this sale was not converted from the live version. It was created as an independent online sale when it became clear that live sales would not be an option at this time.” And because Sotheby’s had experience with online sales in the past, it had proof to show consignors that such a format can work.

Moore added that the results seem to prove online boosters’ contention that “the barrier to entry in online sales is much lower and less intimidating than a live sale.” This time around, nearly one-third of all buyers (29 percent) were new to Sotheby’s. And while the current market is not exactly one where new stars are getting made, it is demonstrating steady interest in the ones who have already arrived. “I think it is a testament to the market’s appetite for quality works at attractive prices,” Moore said.