The Back Room

The Back Room: Dirty Dealings

Delving into the case that could undo the Wildenstein dynasty, which nepo babies are teaming up, where art sales were most sluggish, and more.

Delving into the case that could undo the Wildenstein dynasty, which nepo babies are teaming up, where art sales were most sluggish, and more.

Artnet News

Every Friday, Artnet News Pro members get exclusive access to the Back Room, our lively recap funneling only the week’s must-know intel into a nimble read you’ll actually enjoy. (If you were forwarded this email, you can subscribe here.)

This week in the Back Room: Delving into the case that could undo the Wildenstein dynasty, which nepo babies are teaming up, where art sales were most sluggish, and much more—all in a 6-minute read (1,820 words).

Programming Note: The Back Room is on vacation next week. Our next newsletter will be in your inbox September 8.

The former Wildenstein Building. Photo by Jim Henderson, Creative Commons.

Next month, what could become a landmark trial for the global art trade begins in France’s highest civil and criminal court.

This week in the New York Times’ magazine, Artnet News’s own Rachel Corbett dug into dynastic art-dealing Wildenstein family’s finances and ongoing legal woes.

The story of the family is twisted and fascinating in its own right, as well as incredibly revealing about the clandestine ways that art changes hands on a global scale, making our industry the “largest legal, unregulated market,” as a 2020 U.S. Senate subcommittee put it.

To many in the art industry, the Wildenstein family is best known as collaborators with Pace Gallery. In 1993, Arne Glimcher accepted what he characterized as a flattering offer from the Wildensteins to form a joint venture to sell Pace’s contemporary roster alongside the Wildensteins’ Impressionist and Old Master works. The collaboration didn’t work, however; their client bases were too different. The venture was a sort of last ditch effort to remain relevant in a changing art market where Old Master work was less in demand. Pace bought its stake and inventory back from the Wildensteins in 2011.

But while taste changes, the machinations that make these dynastic families such powerful art-market engines have not.

The Wildensteins pioneered a method of art market manipulation that involves buying up a critical mass of blue-chip artwork by one artist to corner a market. For example, the family owned 500 Pierre Bonnard works acquired by purchasing inheritance rights and then outspending its adversaries in court.

The Mugrabi and Nahmad families followed a similar stockpiling template to build their respective empires, Corbett points out. “Those who complain that the art market today operates more like the stock market often blame these families, who shifted a value system once driven by connoisseurship to one based on the law of scarcity…As the Wildensteins proved, families can be structured like corporations,” she wrote.

That could now be coming to an end, at least in France.

It began, as so many twisted tales of the art trade do, with one of the “three D’s” (those being debt, divorce, or death). Daniel Wildenstein, the third Wildenstein to lead the family business, passed away in 2001, and left his wife, Sylvia, locked in a gnarly battle with her stepsons over the family’s vast wealth. Sylvie hired attorney Claude Dumont Beghi to help her get her stake after the younger Wildensteins claimed Daniel died in financial ruin—an unlikely scenario.

Through exhaustive research over many years, Dumont Beghi managed to uncover how the Wildenstein dynasty, which spans “nine companies registered in Ireland, four trusts on three islands, a handful of galleries and real estate companies and bank accounts in at least four countries,” moves money and art across continents. She revealed a complex web of hidden assets that relies on mechanisms like off-shore accounts, irrevocable trusts, and tax havens such as the Cayman Islands and Guernsey.

Sylvia passed away in 2010, but the project she and her attorney began is just now gaining steam. Two years ago, French authorities reopened a 2017 tax fraud and money laundering case, in which members of the Wildenstein family were acquitted on the grounds that foreign trusts, at that time, were a muddy legal area. The re-trial begins in September. (One matter at issue in the upcoming trial is whether trustees took direction from the Wildensteins in administering irrevocable trusts that legally must be independently managed).

The stakes are high. The Wildensteins could be saddled with a tax bill in the hundreds of millions. More importantly, the unprecedented case could also serve as a blueprint for how to track the proceeds of art sales through the labyrinth of trusts, shell companies, and free ports around the world engineered to impede just that.

Corbett reports that “the evidence…brought forth has persuaded prosecutors that the Wildensteins are a criminal enterprise, responsible for operating, as a prosecutor for the state once put it, ‘the longest and the most sophisticated tax fraud’ in modern French history.”

The case could forever change how high-end assets are traded and held by the uber-wealthy, at least in the European Union. A study from the U.S. Treasury Department estimates that money laundering and other financial crimes in the art market in the United States amount to about $3 billion a year. The same study points out that conducting due diligence in art sales is purely voluntary in the U.S., and concludes that that “presents a vulnerability to the U.S. financial system.”

At the root of this shady system is one fundamental value: privacy. “In my family, we have elevated discretion to the level of muteness,” Daniel Wildenstein wrote in his memoir. As Corbett writes, “The family took such pains to protect their inventory that no one knows what they really have, perhaps not even them.”

The latest Wet Paint tracks the two self-identified nepo babies behind a new pop-up gallery, and the latest developments out East, where art dealers run afoul of zoning and the plot of Montauk Turf War 2023 thickens…

Here’s what else made a mark around the industry since last Friday morning…

Art Fairs

Auction Houses

Galleries

Institutions

Tech and Legal News

“Obviously, most people in my world thought it a little crazy to go into the NFT space now. The market is nowhere near what it was—for me, that’s an opportunity. If Web3 is the future, now is the time to enter, after the hyped craziness. It has allowed me to reinvent myself in a new medium and connect with the next generation of collectors. It’s tremendously exciting.”

—Yue Minjun, the Chinese contemporary artist famous for his “laughing man” paintings, spoke to Artnet News about the timing of his NFT venture.

© 2023 Artnet Worldwide Corporation.

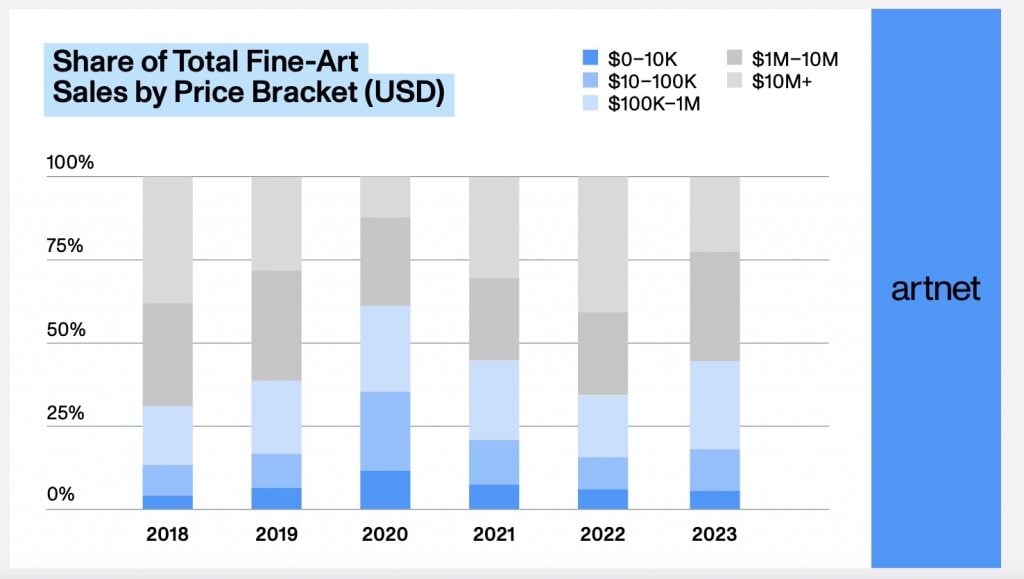

As we continue to dissect the art market’s slowdown in the first half of 2023, we’re looking closely at which price brackets performed best during that period (January 1 to May 20) via Artnet News’s semi-annual Intelligence Report.

Experts told Intelligence Report author Julia Halperin that buyers became more price sensitive just as the glut of “extraordinary material”—i.e. the collection of late Microsoft founder Paul Allen and the spoils of Linda and Harry Macklowe’s divorce—that hit the block in 2022 was exhausted. This fueled sluggish sales numbers overall, but different price brackets fared very differently.

Sales of works for between $100,000 and $1 million were up 18 percent, the best-performing segment of the market by price. Meanwhile, sales of art valued at more than $10 million fell by 51 percent. But sales of pieces priced between $1 million and $10 million were up 14 percent in the period, likely buoyed by the lack of inventory over $10 million.

—Guelda Voien