Analysis

The Gray Market: Why the Met’s Ticket Prices Are Not the Problem (and Other Insights)

Our columnist delves into the Met's controversial new admission policy—and explains why a lasting solution won't come from the box office.

Our columnist delves into the Met's controversial new admission policy—and explains why a lasting solution won't come from the box office.

Tim Schneider

Every Monday morning, artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, tackling a single issue sucked all the air out of my room….

For anyone in the industry who has been frozen inside a block of ice since New Year’s, on Thursday the Met officially announced that it will begin charging mandatory admission to non-New York adults and non-Tri-State adolescents, effective March 1.

Adults in this cohort will be asked to pay $25. Seniors get a discount to $17. Students will pay $12, while children under age 12 continue to get into the museum free. The Met will remain “pay what you wish” for New Yorkers, on the condition that they provide an ID or other proof of residency. (For more context and detail, you can read Met president/CEO Daniel H. Weiss’s explanation for the decision and policy details here.)

The change immediately unleashed an army of critics, some of whom have been bracing for combat on this issue since the Met and the city clarified the museum’s right to charge suggested admission in October 2013. On Thursday, Roberta Smith and Holland Cotter at The New York Times led what felt like a nearly media-wide assault against the museum, with plenty of other well-respected figures joining the charge from under mastheads around the industry. (The Times’s editorial board was an exception.)

I got agitated myself after the announcement, especially since the most memorable statistics I’d seen on this issue while I was living in Los Angeles—the Broad Museum’s first-year attendance report—implied a link between gratis admission and audience diversity. Among the (free) institution’s over 823,000 visitors from 2015-2016, a staggering 62 percent identified as an ethnicity other than Caucasian. That’s nearly triple the average found in a 2015 study of US museum attendance by the Morey Group.

Still, if we’re going to evaluate the Met’s new policy fairly, we have to separate the controversy into two distinctive questions. The first is philosophical: Should museums be free for everyone, particularly during a time when sociocultural divisions within the US seem to be worsening by the minute? My personal answer to that would be “yes.” And that position is the rare one where I appear to have a seat at the table with the majority.

The second question, though, is one that I haven’t seen addressed yet, and one that transforms me right back into the Kodiak crashing the campground: Does a more comprehensive dive into the data show that admission fees meaningfully affect museum attendance? More specifically, do free museums ACTUALLY attract larger, more diverse audiences than those that charge for entry?

And after spending Friday and Saturday reviewing the research, I’m here to report that the answer appears to be a resounding “no.”

The Met’s entrance hall. Photo Michael Gray, via Flickr.

For anyone who wants to go deep on the academic literature themselves, by far the single best source I’ve found is this chart-rich blog post by Colleen Dilenschneider, the chief market engagement officer for research and analysis firm IMPACTS, titled “How Free Admission Really Affects Museum Attendance.”

There, Dilenschneider, who works extensively with nonprofits and cultural organizations, aggregates studies published by the Journal of Cultural Economics, New Zealand’s Ministry for Culture and Heritage, the UK Council for Museums, Libraries, and Archives, and other credible sources from around the world—all of which strongly suggest that my intuition about the pernicious effects of museum admission fees is as wrong as sexting at a funeral.

I’m not going to refabricate every rung in Dilenschneider’s argument here. Instead, I’ll just highlight what were, to me, the most surprising and consequential findings.

To quote Dilenschneider’s summation of this “landmark” study by sociologist Volker Kirchberg, “admission cost is a secondary factor when considering a museum visit.” More specifically, “a lack of time… or a simple lack of interest… were far more important factors in one’s decision not to visit museums than were admission fees.”

In separate research on New Zealanders who had never visited a museum, about four and a half times as many respondents identified time constraints (49 percent) rather than cost (11 percent) as their main impediment. In another study, four times as many surveyed Brits did the same, by a count of 32 percent to just 8 percent.

Among American respondents who intended to visit cultural attractions for the first time within one of six different time periods (ranging from one week to two years), every surveyed group judged itself either just as likely or EVEN MORE LIKELY to attend one that cost $20+ as one that cost nothing. (For the curious, these results, to quote Dilenschneider, come “from the National Awareness, Attitudes, and Usage Study of Visitor-Serving Organizations (which is updated annually and has tracked the opinions, perceptions, and behaviors of a sample population totaling 98,000 US adults).”)

Per research by the UK’s Department of Digital, Culture, Media, and Sport (DDCMS), even in cases where overall attendance figures improved after institutions decided to go admission-free, the most substantial bump often came courtesy of a group that Dilenschneider and her peers call “high-propensity visitors,” or people who were already going to museums before anyway. In other words, eliminating ticket prices generally compelled existing audience members to return more often, but did little to entice large numbers of new visitors.

Nor is the DDCMS an obscure government department with no skin in the game. It works with 43 agencies and public bodies across the UK, including museums like Tate, the National Gallery, and the British Museum—all of which went admission-free in 2001 and became the subject of this very study years later.

In total, then, we’re left with a substantial body of research that has concluded:

If we want to argue that the Met’s mandatory admission fee for out-of-towners is horrifically exclusionary, then, looking for existing evidence from the social sciences is about as helpful as a dead battery in a getaway car.

Metropolitan Museum. Photo: Flickr Creative Commons.

Now, all of the above being said, I think it’s crucial to recognize that none of the findings I’ve cited so far necessarily rules out that ethnic and/or class differences may have heavily influenced the results. It may just be that those differences register at a deeper level than numbers alone can show.

To elaborate a little: It seems entirely possible, if not probable, that the reason “lack of time” and another major factor, “lack of transportation,” were cited as the most pressing barriers to museum entry is that people of color have been structurally undermined by generations of discriminatory economic and housing policies. (It’s a lot tougher to get to museums, which are generally in very desirable areas of cities, when you or your ancestors have been systematically barred from renting in good neighborhoods, attending good schools, and getting good jobs for generations, for instance.)

Similarly, none of these studies directly addresses the effects of institutions’ asking visitors to prove residency at the door by showing ID (or, somewhat ridiculously, utility bills or bank statements). Maybe this associated move ends up discouraging even locals—particularly POC, the young, and the working class, as these statistics suggest—to a degree that makes the Met’s policy shift more insidious for audience size and composition than the research above captures.

However, if these caveats are valid, evidence says that eliminating ticket prices is not the way for museums to reverse course.

Instead, if we really want to focus on diversifying and expanding audiences at the Met and other institutions, particularly across racial and class lines, then we should look at more targeted, more progressive options.

Statue of Diana by Augustus Saint-Gaudens at the Met. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

Just a few weeks ago, my colleague Julia Halperin wrote about how Atlanta’s High Museum tripled its nonwhite audience since 2015. Under director Rand Suffolk, the institution has implemented strategies such as “allowing curators to tailor projects to their own audience,” often by featuring more artists of color, particularly African Americans; marketing the High more as a living, breathing “destination for families and young professionals” than as a venue existing primarily for the sake of housing a handful of special exhibitions; and significantly diversifying its staff, from docents to curators, so that the community as a whole could feel more welcome and better represented on campus.

And researchers say that these solutions are more effective than simply tweaking (or obliterating) admission prices. As Dilenschneider writes in a separate post on evolving engagement models, “Access isn’t primarily about price. It’s about eliminating every barrier to engagement.”

With that in mind, it’s notable that a true admission-fee drop played little role in the diversity success story at the High. While the institution technically lowered the entry fee for adults (formerly $19.50), as well as seniors and students (formerly $16), to $14.50, it simultaneously raised the price for children to the same figure (up from $12). As Andrew Russeth wisely noted in ARTnews, this “adjustment” meant that families with two children would pay the same amount as in the old price structure, while families of five and up would actually pay MORE.

So the High’s encouraging results square with the social-science research, bolstering Dilenschneider’s claim that museums and other cultural entities are being “inappropriately emotional about business matters” like ticket prices.

But if charging admission is largely a non-factor, then it naturally leads us to ask what’s really triggering all the rhetorical artillery aimed at the Met.

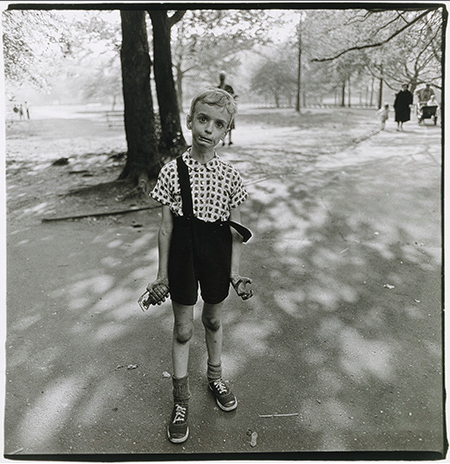

Diane Arbus, Child with Toy Hand Grenade (1962).

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

While it’s always hazardous to pop-psychologize, especially on a macro level, I’ll attempt it here because the Met’s shift on admission fees is, again, the rare issue where my initial reaction aligned with the most popular one.

Certainly part of the issue is visibility. A ticket-price change by arguably the most prominent museum in the world will always be big art news. As Marion Maneker argued in a blistering critique of Roberta Smith and Holland Cotter’s response piece on Friday, it’s also a problem that can look deceptively easy to solve from the outside, particularly in light of the Met’s seemingly colossal financial resources. (For one reason it’s more complicated, I recommend this short tweet thread on the Met’s endowment and the boring-but-important concept of unrestricted operating revenue.)

But the museum’s shift on admission fees has also caused so much friction because many of us in the art world think we can see in it the outlines of unjust structural conditions in the wider world—conditions that we often feel powerless to affect on our own.

Smith and Cotter certainly both do. Maneker slams the former for “comparing the effort to Nativism” and the latter for alluding to the increasingly virulent anti-immigrant campaign emanating from Washington, specifically vis-à-vis the Met ID’ing New York residents to confirm entry privileges.

I’m more sympathetic to Smith and Cotter’s analogies. But they also solidify that the media melee over the Met’s ticket policy is largely a proxy war, perhaps made all the more intense by the perception that our tiny militia might actually be able to win such a narrow victory on our own turf.

Yet this is likely a misdirection of resources (albeit an understandable one). In my colleague Ben Davis’s book, 9.5 Theses on Art and Class, he argues convincingly that artists and art lovers who want real sociopolitical change would do better to focus less on political gestures made inside galleries than on organizing for social causes outside of them.

I’m not saying that Daniel H. Weiss and company are blameless, let alone perfect, for installing a less open policy at the Met’s gate. But if we’re offended by the museum’s shift as a matter of principle, we—and I most definitely include myself in this suggestion—might do better to channel our ire and energy past the Met’s boardroom to the larger, more systemic problems casting the shadow the museum lives inside.

We can’t solve those larger problems on our own. But that doesn’t mean we can’t be a small part of a coalition big enough to succeed where our insular community would fail. And that’s truly a goal worth sharpening our teeth for.

That’s all for this edition. Til next time, remember: There’s no such thing as a free museum. It’s just a matter of who’s paying the costs—and why.