Analysis

The Gray Market: Why We Need To Rethink Our Definition of the ‘Middle Market’ (and Other Insights)

This week, our columnist surveys the New York evening sales for meaningful activity.

This week, our columnist surveys the New York evening sales for meaningful activity.

Tim Schneider

Every Monday morning, artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, we survey the New York evening sales for meaningful activity…

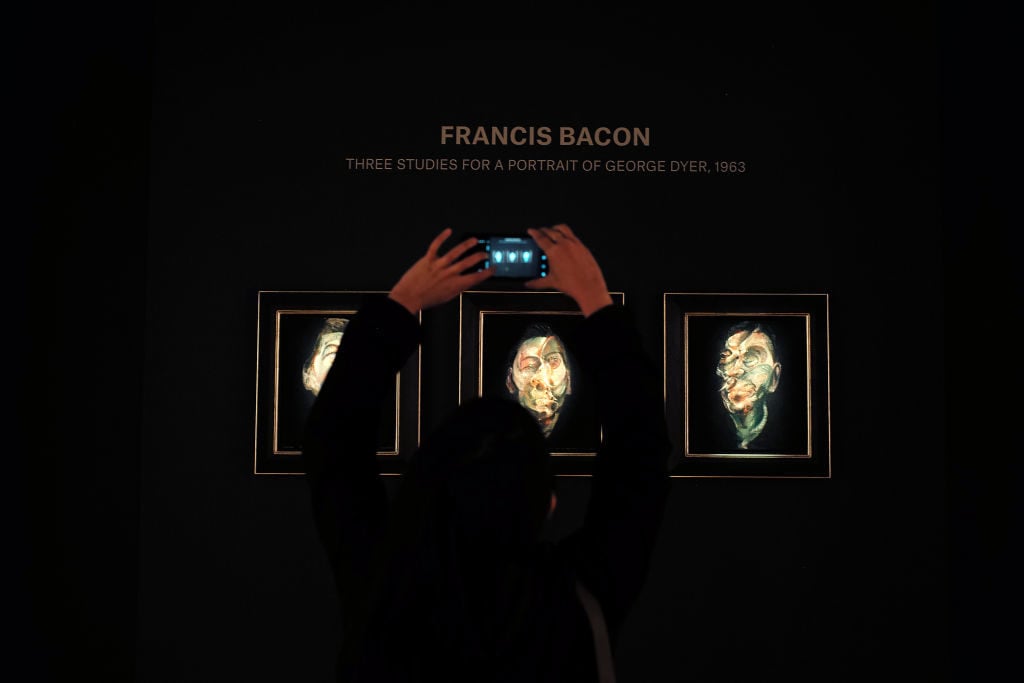

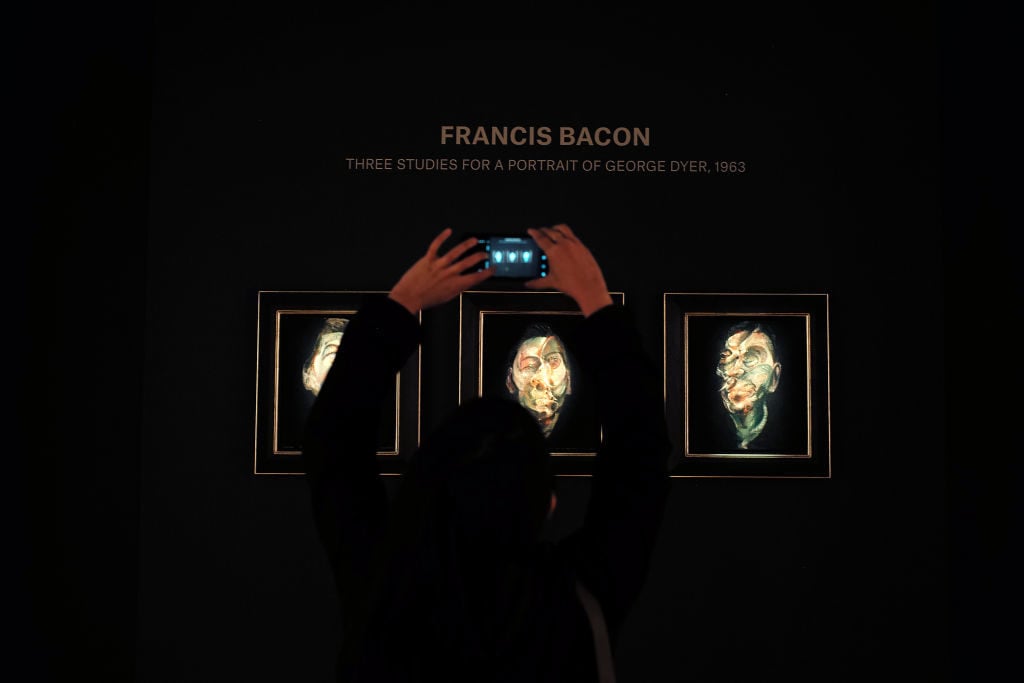

MANAGED DEMOCRACY: In a result so over-the-top that it barged into my pro basketball Twitter feed, on Thursday Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Untitled (1982) sold for $110.5 million (including fees) at Sotheby’s postwar and contemporary evening sale.

Before the obvious sources could even elbow their way to the nearest reporter to begin conflating auction-price history with art history––honestly, if the Times recap didn’t include Jeffrey Deitch proclaiming something like “[Basquiat]’s now in the same league as Francis Bacon and Pablo Picasso,” I would have agreed to swallow a mouthful of street pennies––the winning bidder quickly dispelled any uncertainty about his identity.

Moments after the sale ended, Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa posted an Instagram shot of himself with his new trophy acquisition, captioned with an earnest-seeming message about his desire to share his experience of the work “with as many people as possible.”

Yusaku Maezawa gazes adoringly at his new artwork. Image via Instagram.

Even if we give Maezawa the benefit of the doubt about his sincerity, though, I’d argue that his statement and his chosen platform reinforce a potentially unsettling reality about a much-hyped industry trend. Over the past several years, practically every art-tech startup worth its Soylent subscription has made some kind of overture toward “democratizing the art world,” i.e. amping up the accessibility of one of humankind’s most socioeconomically discriminating trades.

And yet, as more and more of these idealistic ventures spiral into the abyss each quarter, prices at the upper end of the art market have generally continued climbing to unprecedented heights––heights that increasingly distance much of the work itself from anyone incapable of buying their way onto a SpaceX flight.

So what’s happening here? My sense (and good grief, do I have more to say about this soon) is that, in many ways, technology is in the process of introducing the art industry to something like what the Kremlin calls “managed democracy“: a society in which the average citizen enjoys just enough power for the ruling figure(s) to plausibly deny they’re in complete control of the scene.

Jean Michel-Basquiat’s Untitled (1982). Courtesy of Sotheby’s New York.

I’m not saying that market-making galleries or ultra high-net-worth collectors are disenfranchising rank-and-file art lovers in the same way as a guy who would orchestrate an opportunity to deny an international cover-up while wearing hockey pads.

I’m just saying that it’s possible for tech to hand a larger audience more information about more industry developments more quickly than ever… while at the same time, largely reducing said audience’s relationship with art to the superficially digital. Meanwhile, elites continue to silo great works among themselves at prices that public institutions can’t match.

Case in point: It’s nice that almost 17,000 people have liked Maezawa’s Instagram of Untitled so far, but I’m not sure it offsets his reported plans to house the piece in his in-development private museum in Chiba, Japan.

To be clear, I think there are many more innovative advantages to the integration of art and tech than what we’re seeing here. Maezawa’s peers could also prove me wrong even on the traditional front by disseminating their collections as widely as Maezawa has suggested he’ll loan Untitled. But Sotheby’s record-setting Basquiat sale also serves as a great reminder that democracy is often a lot more complicated than it sounds. [The New York Times]

Cy Twombly’s Leda and the Swan (1962), which sold for $52.9 million at

Christie’s postwar and contemporary evening sale. (Jewel Samad/AFP/Getty Images)

THE MOBILE MIDDLE: The night before Maezawa bid his way atop the headlines, Christie’s achieved the cognitively dissonant feat of holding a postwar and contemporary evening sale that was both its highest-grossing in years ($448 million total, including fees)—and yet still “[lacking] oomph,” according to the reliably sharp Nate Freeman. How do we reconcile those two concepts? I think this tiny beacon later in his recap helps cut through the haze:

“Even someone in the Siberia of [Christie’s] Woods Room, which pens in overflow attendees, bid hard enough to nab a Donald Judd for over $800,000. ‘It’s been a while since we had a purchase from the Woods Room,’ auctioneer Jussi Pylkkanen said, dryly.”

I thought about this detail again the next evening when I read Robin Pogrebin’s previously mentioned recap of Sotheby’s contemporary sale––a sale that was widely deemed much more successful than its Christie’s counterpart for eclipsing its high estimate by nearly $40 million (largely thanks to Maezawa’s Basquiat thirst).

The connection came in a quote by advisor Morgan Long of the London-based Fine Art Group (a firm whose name I would advise you to never, ever abbreviate): “Sotheby’s had a lot more works in the middle range around $5 million to $10 million that appealed to the market.”

What’s visible through the twin prism of these statements is the result of a years-long bend in what the “middle range” (or “mid-market”) means to the art industry, especially when it comes to resellers.

Even after the 2008 recession began fading, knowledgeable analysts could still justifiably define that price band as something like $5,000-70,000. More bullish sources might have pushed the outer boundary to, say, $100,000, or maybe even something like $500,000, if they were truly on the verge of goring a rodeo clown.

But $5–10 million? Calling this “the middle range” puts us in a different arena altogether––one where a bidder who’s not even deemed worthy of a seat in Christie’s main auction room can chuck $800,000 at a Judd not even deemed worthy of a reference in the post-sale press release. And if there’s a better emblem than that of how much dumb money has charged into the market in the past 10+ years, I don’t know what it is. [ARTnews]

Peter Doig’s Rosedale (1991) at the Phillips salesroom. (Photo by Dominic Lipinski/PA Images via Getty Images)

SPIN DOCTORS: Finally this week, as a reminder that the sell job doesn’t end just because the night’s final lot has exited stage left, let’s survey some of the acrobatics that auction officials undertook to spin attention away from some of their events’ less desirable outcomes.

On Tuesday, Anna Louie Sussman found Sotheby’s Simon Shaw arguing that his house’s Impressionist and Modern evening sale had “a hell of a lot of momentum” based on “the fact that, on average, four people competed for each lot, with more than 10 bidders vying for at least one work.”

Both of which are nice statistics to have in your holster, if you’re trying to shoot down talk about how, a few hours before showtime, the would-be consignor of your prime lot, Egon Schiele’s Danaë (1909), was unhappy enough with the bidding prospects you’d secured to drop your sales agreement through a trap door like an underperforming James Bond henchman. (To her credit, Sussman structured her recap around the lot’s eleventh-hour disappearance.)

The spin cycle continued on Wednesday, when Nate Freeman (in his previously mentioned piece) caught newly promoted contemporary department co-chair Loïc “Not the Ghostbusters Villain” Gouzer literally blaming Donald Trump for preventing Christie’s postwar sale from hitting escape velocity.

The connection? The wealthy’s urge to spend might have been temporarily suppressed by a negative day in the financial markets––one possibly caused by, I don’t know, the dawning prospect that the highest office in the land may be occupied by a justice-obstructing kleptocrat “whose thoughts are often just six fireflies beeping randomly in a jar,” per David mother-effing Brooks, of all people. Was there some truth to Gouzer’s theory? Probably, yes. But it’s also a great way to pass the proverbial buck.

All that said, my favorite revisionist history of the week came from Phillips, which proudly advertised that its “Evening Sale of 20th-Century and Contemporary Art… [sold] 100 percent by lot” in its press release—despite the fact that a big-ticket Gerhard Richter abstract got completely smoke-bombed out of the lineup pre-auction, as reported by my colleague Henri Neuendorf.

Yes, technically, the house sold everything that it offered. But it didn’t offer everything it was supposed to sell! So while the two previous examples arguably qualify as alternative facts, Phillips’s “no-lot” narrative is straight-up art-sales gaslighting: Whether online, in the catalogue, or during the preview days, what you thought you saw was never actually there.

This is not a new tactic in the auction sector. But when it comes to the people not paying close attention to detail, the oldest tricks in the book are still around for a reason. [Artsy, Artnet]

That’s all for this edition. ‘Til next time, remember: Under cover of darkness, almost anything can happen.

You can read The Gray Market’s full archive, as well as the latest posts, here.