The Gray Market

How Artnet Oracle Tim Schneider’s 10 Highly Specific Art-World Predictions for 2021 Worked Out (and Other Insights)

Our columnist grades the predictions he made at the start of 2021 to see where he went right (and wrong).

Our columnist grades the predictions he made at the start of 2021 to see where he went right (and wrong).

Tim Schneider

Every week, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

It’s that time again: time for me to look back at the predictions I made in the year’s first Gray Market to see how my expectations stacked up against the next 51 weeks in the art world. Let’s get right into it, yeah?

Of the five fairs above, four went ahead as they were scheduled back in early January. Frieze Los Angeles, however, was called off in April; an online viewing room stood in for the live fair during the same dates. Explaining the decision, a fair spokesperson cited “ongoing uncertainty” around the city’s public-health situation and an organizational choice to focus on the expo’s 2022 edition, which (as of my writing) is set to open February 17 in the roomier digs of 9900 Wilshire Boulevard.

But my former colleague Nate Freeman relayed chatter about other complications spilling out from behind the curtain, including reluctance by municipal officials to permit Frieze to turn some of the city’s great Modernist homes into improvised fair booths. (Tax laws allegedly prevent private homes from operating as commercial businesses in the City of Angels.) Frieze reps declined to comment on Wet Paint’s alternate history of the west-coast kibosh.

Regardless of the reasons, though, this prediction falls just short.

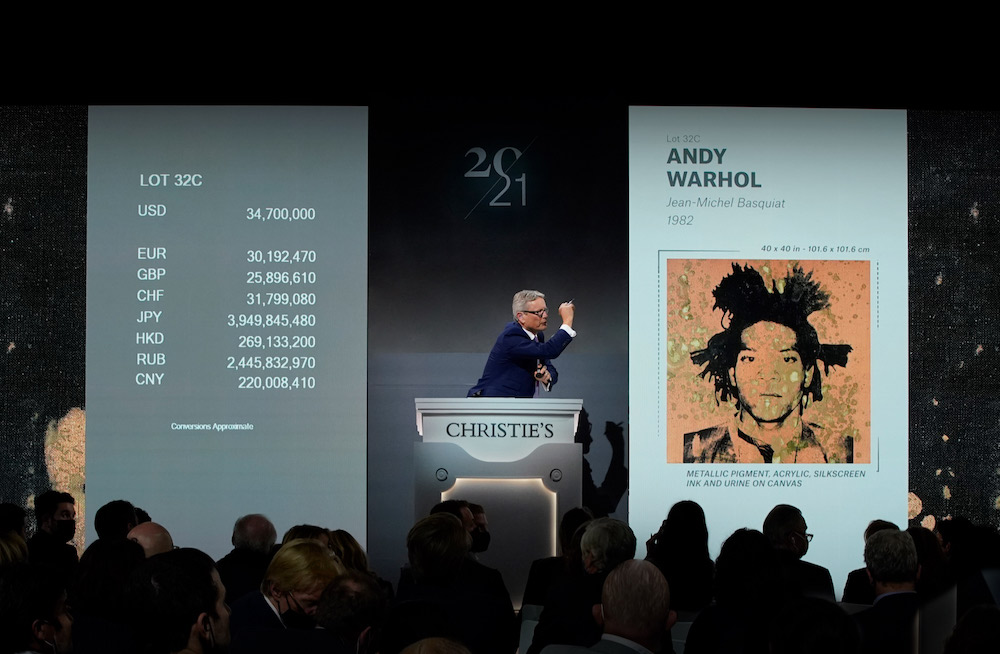

Jussi Pylkkanen selling Andy Warhol’s portrait of Jean-Michel Basquiat (1982) at Christie’s in November 2021. Image courtesy Christie’s.

Bidders had won more than 358,000 fine-art lots around the globe as of December 20, 2021 per the Artnet Price Database and Artnet Analytics. That’s a higher number of works moved by the sector than in every full year on record dating back to 1983… except for 2011, when the international gavel gang found buyers for more than 367,000 fine artworks worldwide.

So after selling north of 1,000 such lots per day on average for almost 51 weeks, auction houses were only about 9,000 sales behind the all-time record with 11 days of results still to be compiled this year. In short, it’s a squeaker. The gods of accuracy compel me to reserve judgment on this prediction until the full year’s results are in. Sorry!

KAWS, SPOKE TOO SOON (2021). Courtesy of Skarstedt, New York, ©KAWS.

Fortunately for me and my fellow completists, results on this one are already firm enough to enable a ruling even with a few days’ worth of data yet to be logged. Works by Botticelli had raked in more than $94 million under the hammer by December 20, 2021, according to the Artnet Price Database, with $92.2 million of the total coming from the sale of Portrait of a Young Man Holding a Roundel (ca. 1470–80), one of just three portraits by the artist known to be in private hands when bidding commenced inside Sotheby’s New York salesroom January 28.

Meanwhile, KAWS’s auction results enthusiastically X’d out the eyes of every one of Botticelli’s in-category competition by December 20. The man known to friends as Brian Donnelly amassed more than $34 million by gavel strikes, nearly twice as much as second-place Old Master Anthony van Dyck (roughly $17.7 million) and third-place Leonardo da Vinci (about $17.2 million).

P.S. This prediction felt a lot more subversive before NFTs went interstellar. Case in point: Beeple (AKA Mike Winkelmann) outsold Botticelli by about $4 million on just two lots offered by Christie’s this year: the $69.3 million NFT-backed digital collage Everydays: the First 5000 Days in March, and the $29 million ever-changing video sculpture HUMAN ONE in November. What a world… .

On the for-profit and nonprofit sides of the U.S. art industry alike, the Paycheck Protection Program replaced tens of millions of dollars’ worth of business lost to the pandemic—and likely headed off dozens of lawsuits that would have aimed to force reluctant insurance carriers to pay out for claims related to COVID-induced shutdowns.

On the other side of the Atlantic, a January ruling in the U.K.’s High Court established clear guidance requiring insurers to make policyholders whole again after “business interruption” losses triggered by lockdowns. Rudy Capildeo, a partner at the law firm Charles Russell Speechlys LLP, said the decision was a boon for more than 50 arts organizations (comprised of what he termed “museums, galleries, dealers, and other art market professionals”) with claims represented by the firm on a no-win, no-fee basis.

A courtroom setup awaiting a witness. Photo: Friso Gentsch/dpa (Photo by Friso Gentsch/picture alliance via Getty Images)

Still, this one-two punch of government advocacy wasn’t enough to keep at least a few domestic arts and culture businesses from taking a fight with their insurers to the courts. After a district court judge threw out a suit brought by Manhattan’s Guy Hepner Gallery against Sentinel Insurance Company, Hepner appealed the ruling in April. In the nonprofit realm, three different U.S. cultural institutions filed suit against their insurers for pandemic relief between February and August 2021, according to the University of Pennsylvania’s COVID coverage litigation tracker: the Los Angeles County Natural History Museum, the New York Botanical Garden, and New York’s American Museum of Natural History.

Since I can picture hard-liners moaning that the institutions above don’t qualify as art museums, I’ll point out that the New York Botanical Garden’s attorneys filed suit against the Allied World Assurance Company only a few weeks before the debut of its blockbuster Yayoi Kusama exhibition, “Kusama: Cosmic Infinity.” Don’t hate me, hate contemporary art’s growing refusal to observe purists’ boundaries ¯\_(ツ)_/¯.

I did a crap job of writing this prediction in a way that could be objectively evaluated, so I decided to grade it by checking up on nine major art institutions in NYC and L.A. that have traditionally held a gala (by whatever name) between the spring equinox and summer solstice. Of those nine, five canceled, postponed, or digitized their spring benefit this year: the Met, the Brooklyn Museum, the New Museum, the Jewish Museum, and MOCA Los Angeles. Better luck to them (and me) next year.

Lucas Cranach the Elder’s Lucretia, deaccessioned by the Brooklyn Museum of Art in September 2020 with an estimate of around $1.8 million.

As a refresher, I cooked up this prediction based on the April 2020 decision by the Association of Art Museum Directors to allow member institutions to “use the proceeds from deaccessioned art to pay for expenses associated with the direct care of collections” through April 10, 2022. (The AAMD traditionally only allows its members to sell works for the sake of buying more art.) After what opponents of more permissive deaccessioning policies portrayed as an orgy of institutional sales last year, expectations were that we would see even more this year as pandemic restrictions wore on and financial hardships piled up.

However, when I reached out to the AAMD for confirmation of how many of its member institutions deaccessioned at least one piece in 2021 versus 2020, the organization’s executive director informed me that they don’t track that information. Which is a great reminder that the AAMD (like much of its constituency) is really just a group of people doing the best that it can in the moment with extremely limited resources, not the omniscient force it is often tacitly characterized as.

Anyway, in the absence of a single definitive list, I queried the Big Three auction houses (Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips), which law and custom enshrine as the sales agents for the vast majority of museum deaccessions. Their responses once again clarified that the deaccessioning discourse tends to oversimplify the realities of the practice.

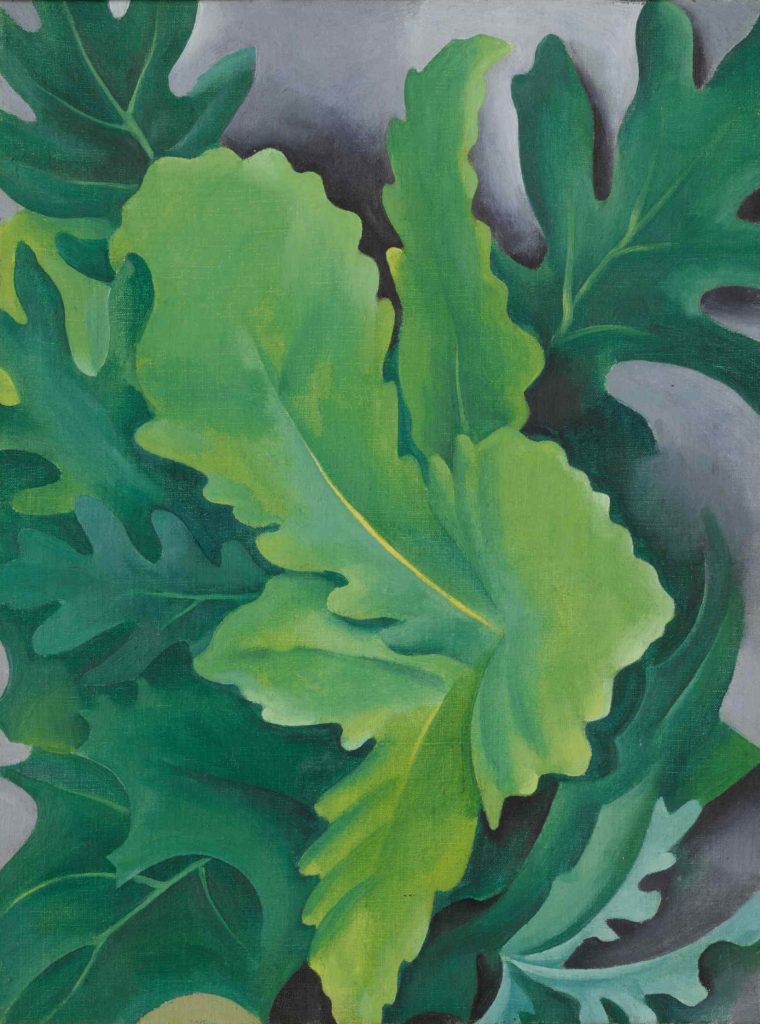

Georgia O’Keeffe’s Green Oak Leaves (ca. 1923) was the star lot of the Newark Museum’s sale in April 2021. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

A Christie’s spokesperson confirmed that the house consigned works from 36 U.S. and international art institutions in 2020, versus 28 in 2021. A Sotheby’s rep declined to provide lists of institutional consignors, but did relay that the house sold $63 million worth of art specifically for deaccessioning purposes in 2020, versus $79 million worth in 2021. Phillips declined to comment. So it seems like we have one datapoint from one source suggesting my prediction was wrong, and a different datapoint from a different source suggesting my prediction was right.

Where all of the available information agrees, however, is that the difference in deaccessioning activity between 2020 and 2021 was relatively minor. Underscoring this conclusion is the fact that in 2019—the year before the AAMD loosened its guidelines around the practice in response to COVID—Sotheby’s generated $122 million in deaccessioning-related sales, nearly twice as much as in 2020.

All of this suggests that shifts in AAMD policy have far less influence over museums’ decisions than the debate over deaccessioning tends to assume. And that’s a prospect worth keeping in mind long after the pandemic fades.

Every time I do this year-end evaluation, I find one prediction that immediately makes me say to myself, “Well, that was dumb.” This is that prediction for 2021.

For the average gallery, it seems that the costs of regularly updating a web page/mini-site throughout the year have proven to be far lower than the benefits of consistently offering one or more works for sale online. That should have been easy for me to anticipate, but my antipathy for the OVR industrial complex (which one collector memorably described to me in fall 2020 as “a nonstop onslaught of art”) momentarily overrode my analytical thinking. Next time your emotions threaten to overwhelm your judgment, be better than me.

New York Governor Kathy Hochul attends the 2021 New York City Veterans Day Parade on November 11, 2021. (Photo by Theo Wargo/Getty Images)

I premised this prediction on three underlying ones: first, that we would see a tsunami of evictions and foreclosures based on financial hardship suffered by tenants and mortgagors in New York and/or another major art city; second, that landlords’ difficulties in finding new tenants for the vacant spaces at market rates would incentivize them to look for appealing stopgaps; and third, that the uncertainty of the pandemic would compel a significant number of dealers to forego renting permanent spaces and instead embrace itinerant programming.

None of those underlying assumptions really panned out. In New York in particular, landlords’ efforts to defeat state and federal eviction moratoriums have largely been rebuffed by the courts, meaning thousands of commercial and residential tenants behind on their payments have been allowed to stay put. (In September, Governor Kathy Hochul extended the state’s moratorium through January 15, 2022, and she worked with the state legislature to tweak the law to defeat ensuing legal challenges later in the fall.)

Just as important, we have seen a surprisingly low number of gallery closures in the nearly two years since COVID first shut down enormous chunks of the economy. Combine all these outcomes, and there wasn’t enough demand for this specific type of team-up to manifest.

Members of the International Galleries Alliance (ICA) in a recent Zoom meeting. Courtesy of ICA.

Early October marked the inauguration of the International Galleries Alliance, a nonprofit comprised of more than 100 global dealers (and counting) who have united to confront a series of sector-wide challenges. Those challenges include (in the words of my colleague Taylor Dafoe) “the demands of art fairs, the stratification of the gallery ecosystem, and the imperative to establish more sustainable business practices across the field.”

The crypto art space provided a number of other, more niche examples, but I’ll highlight the Mint Fund, a grassroots organization launched this February to provide crowdfunding and community support to artists—especially BIPOC and LGBTQIA outside North America and Europe—looking to produce their first NFTs. Buying and selling through the Mint Fund gives users the option to donate part of the proceeds back to the organization via the blockchain.

Mint Fund cofounder and crypto artist Ameer Suhayb Carter (AKA Sirsu) told me in March that the collective was receiving “hundreds more applications every couple of weeks.” It has onboarded 44 artists to date, according to its website, and looks poised to keep going strong.

As the old tech-sector adage goes, being too early is the same as being wrong. Given the pitiful state of museum employment in the U.S. and abroad, I still think we’ll end up seeing this jarring outcome sooner than later. We just didn’t get there in 2021. Here’s hoping it’s not the only dystopian shift that the art industry manages to keep warding off as we hurtle kicking and screaming into a new year.

That’s all for another year of the Gray Market. ‘Til next time (when I’ll make my 2022 predictions), remember: if you want to make the universe laugh, tell it your plans.