The Back Room

The Back Room: Brave New World

This week: the covert business of A.I. art generators, the verdict on a new art-world nightlife hub, the uncertainty in June’s auction results, and much more.

This week: the covert business of A.I. art generators, the verdict on a new art-world nightlife hub, the uncertainty in June’s auction results, and much more.

Tim Schneider &

Julia Halperin

Every Friday, Artnet News Pro members get exclusive access to the Back Room, our lively recap funneling only the week’s must-know intel into a nimble read you’ll actually enjoy.

This week in the Back Room: the covert business of A.I. art generators, the verdict on a new art-world nightlife hub, the uncertainty in June’s auction results, and much more—all in a 6-minute read (1,658 words).

________________________________________________________________________________________

A selection of unlabeled artworks generated using Meta AI’s Make-A-Scene program. Photo: courtesy of Meta.

By now, even the art world’s staunchest traditionalists have likely heard about DALL-E, the A.I.-powered software that transforms text prompts into eerily rich, surprisingly accurate images. But excitement about DALL-E’s novelty has also drowned out multibillion-dollar questions about why and how Silicon Valley is monetizing art history.

This week’s Gray Market dug into the issue. Today, we want to walk you through the essentials.

Using A.I. “trained” on hundreds of millions of images, the latest version of DALL-E (technically, DALL-E 2) processes users’ short text descriptions into surprisingly on-point visuals of almost any conceivable subject matter in almost any conceivable stylization—all in a matter of seconds.

So, users could just generate a plain old “astronaut riding a horse,” or something much much more aesthetically targeted, like a “1960s astronaut riding a Palomino, as painted by N.C. Wyeth.” The possibilities are endless, almost instantaneous, and shockingly well informed.

Competing softwares (including Google’s Imagen, Meta A.I.’s Make-a-Scene and independently financed Midjourney) work similarly. DALL-E is leading the conversation largely because its developer has been the most willing to share its progress.

The algorithms fueling the software are guarded tightly—partly for commercial reasons, and partly to prevent a flood of deepfakes and large-scale disinformation campaigns. Failsafes in the current version include watermarking all resulting images and blacklisting the use of political, violent, or pornographic prompts.

A measured rollout to users also buys time for the producers of text-to-image generators to try counteracting the ethnic, sexual, and other biases embedded in so much of the data used to train A.I. models.

A private company called OpenAI, directed by 37-year-old Silicon Valley entrepreneur and angel investor Sam Altman.

Altman formerly served as partner at, and later president of, Y Combinator, the most storied (and likely most successful) startup accelerator in 21st-century tech. Alumni include unicorns Airbnb, Dropbox, and Stripe, among several others who have racked up gaudy valuations.

In 2015, Altman cofounded OpenAI as a nonprofit with Elon Musk. But after Musk left in 2018 to focus on A.I. inside his main moneymaker, Tesla, Altman converted OpenAI to a for-profit company “so it could more aggressively pursue financing,” Cade Metz wrote in the New York Times.

The move paid off. In 2019, Microsoft invested $1 billion in the project.

OpenAI appears to have launched a metered subscription model to license out the software as-is to all interested parties. The firm is also charging other companies a fee to access its APIs, the tools that would allow engineers to build more customized software on top of DALL-E. Even these revenue streams are just the beginning.

The firm’s ultimate aim is to create artificial general intelligence (AGI). AGI is the evolutionary endpoint of A.I. popularized in science fiction: a thinking (and perhaps even feeling) machine that can establish and pursue its own goals, with all digitized human knowledge at its command.

As a hoped-for route to AGI, OpenAI has essentially split human cognition into its component parts, then poured resources into deciphering each one through an individual project with shared fundamentals.

Another OpenAI endeavor, GPT-3, has gotten scarily good at processing natural language. DALL-E works to codify how our brains relate natural language to images. Both are just milestones on the path to OpenAI’s final destination.

Advanced A.I. models like DALL-E and GPT-3 would be impossible without a vast, rich set of training data. Here, the training data is a public resource: everything the world’s population has ever put online. Now OpenAI and its rivals are harvesting this collectively created data for their own gain.

Along the way, DALL-E and its rivals are also stripping all context and meaning from art history, essentially turning individual styles and movements into photo filters to drive corporate revenue. The software is also so intuitive to use that most of us will never think about its technological or economic workings, including how every prompt doubles as unpaid research-and-development labor for Big Tech.

________________________________________________________________________________________

OpenAI has already taken several steps that suggest it is earnest about developing DALL-E for the greater good of all humankind. Yet its actions are still determined by a handful of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, engineers, and financiers. The result? An inherent power imbalance.

Barring a major change, this imbalance is likely to have far-reaching impacts on art, commerce, and wellbeing that no one in OpenAI’s headquarters can fully anticipate. Unless we in the cultural field understand the stakes, there’s little chance that most of us will be able to do more than hang on for the ride, wherever it takes us.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Reception at Zero Bond. Photo by Natalie Black.

In lieu of Wet Paint this week, our scribe Annie Armstrong paid a visit to the latest New York art-world hotspot, Zero Bond, which she found… less than impressive. (And as the Back Room quote of the week proves, she wasn’t alone!)

Here’s what else made a mark around the industry since last Friday morning…

Art Fairs

Frieze London and Frieze Masters (both October 12–16) have announced the exhibitors participating in the fairs’ first edition since the departure of global director Victoria Siddall. (The Art Newspaper)

Auction Houses

Christie’s Ventures, a new division of the auction house, will invest seed funding in tech companies that produce art-market tools. The first business in its portfolio is LayerZero Labs, which helps consumers transfer crypto assets across blockchains. (Artnet News)

Galleries

This September, Pace will permanently close its six-year-old Palo Alto gallery—one of the first blue-chip spaces to open in Silicon Valley—in an effort to consolidate its global operations. (Press release)

Two more established galleries are opening in New York in September: the Manila-based Silverlens, one of Southeast Asia’s premier dealers, in Chelsea; and Luxembourg + Co. on Madison Avenue. (Artnet News, Press release)

Institutions

The veteran German arts administrator Alexander Farenholtz will assume the role of interim director of scandal-plagued Documenta following the resignation of Sabine Schormann. (Artnet News, Press release)

After multiple failed mergers, the financially beleaguered San Francisco Art Institute announced it has closed for good after 151 years. The fate of the school’s prized Diego Rivera fresco remains unclear. (Artnet News)

Obituaries

Pop artist Claes Oldenburg, known for his whimsical public sculptures depicting everyday objects and foodstuffs, died at age 93. (Artnet News)

________________________________________________________________________________________

“I’d rather get drunk on the street.”

—Anonymous critic after waiting all night at Zero Bond, the private haven for cultural and tech elites, for superstar D.J. Diplo to arrive. He never did. (Artnet News Pro)

________________________________________________________________________________________

© 2022 Artnet Worldwide Corporation.

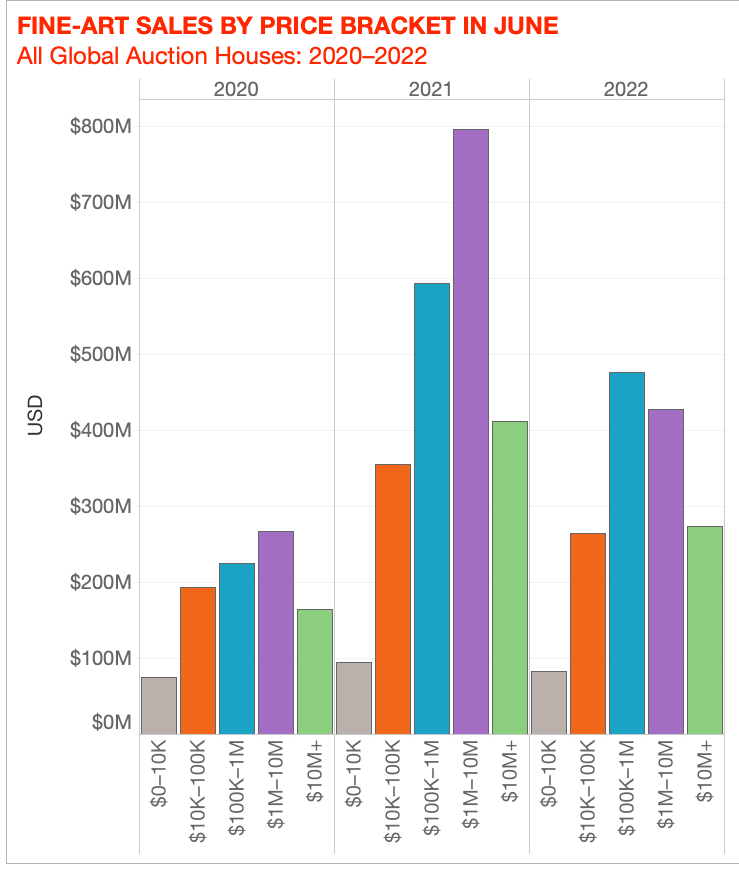

Nearly a full month into the year’s second half, the specter of recession is haunting more and more conversations around the fine-art market. Auction results from June of the past three years do little to quash the fears of a slowdown…

So are sales just stabilizing, or gathering downward momentum as part of a prolonged plunge? No matter where you stand on the market’s prospects for the second half of 2022, one thing is for certain: we’re all going to find out together whether the optimists or the pessimists are closer to the truth.

________________________________________________________________________________________