Every Wednesday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, squinting into the darkness (again)…

BLANK SPACES

Compared to what came before, the 2020s appear to be a golden age for art-industry data. The new abundance of quantified information about the business might have made previous generations of art professionals feel like a Master’s degree in data science from MIT was the most influential program in the industry, not the graduate studios at Yale or UCLA. The growing obsession with data has also contributed to the art industry’s obsession with growing continuously—an obsession shared by governments, central banks, and businesses across sectors of the global economy.

But is the status quo approach to growth quietly speeding us toward a brick wall? A renegade faction of quants argues that it is, and that we can’t see the danger because we’re relying on the wrong metrics. This critique is as relevant to the art economy as it is to the larger economy. Without an imminent U-turn on our approach to data, the business of art risks following the same convenient but ruinous road as policymakers fixated on traditional growth measures for the national economy.

Let’s zoom out. At the macroeconomic level, the one-sided view of growth hinges on gross domestic product (GDP), generally defined as the monetary value of all “finished goods and services” produced inside a given country over a given time period. That sounds at first like a reasonable method of measuring whether the average resident’s quality of life is increasing or decreasing. After all, more goods and services mean there are more people employed to meet more demand generated by consumers with more money to spend, right?

Not necessarily. As a counterexample, take former World Bank economist and University of Maryland professor emeritus Herman Daly. Daly, now 84 years old, has spent his professional life contesting the orthodoxy that GDP-based economic growth is even continuously achievable, let alone automatically good. In fact, the growth agenda can be self-sabotaging if it’s quantified more holistically. He put it this way in a recent interview in the New York Times Magazine:

If [GDP] goes up, does that mean we’re increasing standard of living? We’ve said that it does, but we’ve left out all the costs of increasing GDP. We really don’t know that the standard is going up. If you subtract for the deaths and injuries caused by automobile accidents, chemical pollution, wildfires, and many other costs induced by excessive growth, it’s not clear at all.

In rich countries like the U.S., U.K., and Western Europe, Daly’s proposed alternative is what he calls a “steady-state” economy. Rather than behaving as if endless growth is the optimal path to continuously improving the average resident’s quality of life, steady-state economics supposes that we could better accomplish the goal by making wiser, more creative use of our resources within the limitations we have. How do we find our limitations? By finally starting to quantify the costs of growth, not just the benefits.

My point is that constituents in the art industry (including those of us in the media) are overdue for a similarly comprehensive review of which data is actually valuable, and which isn’t. Otherwise, art professionals across sectors will set themselves up for the types of misadventure that countries like the U.S. are only beginning to try to course-correct after decades of trying to scale up in pursuit of a dangerously incomplete metric.

While that project would incorporate many more components, Daly’s cost-centric framework at least offers a gateway to showing where some of our most prominent datapoints across sectors come up short. Here are four to consider.

Josh Kline, Keep the Change (Texas Roadhouse Waiter’s Head with Cap) (2018). Courtesy of the artist.

1. GALLERIES AS SERVICE PROVIDERS

Everyone knows that dealers are a fortress when it comes to releasing verifiable sales data (even, and maybe especially, during art fairs). The most frequently cited peephole into this sanctum is the dealer survey conducted by Clare McAndrew in “The Art Market,” her industrywide annual report for Art Basel and UBS. The survey’s limitations—such as its dependence on self-reported data and a sample size of under 800 viable responses in the most recent edition—have been debated in fiery tones over the years (and are acknowledged by McAndrew herself), so I won’t pour more gasoline onto those eternal flames. What I can say definitively is that practically everyone but the dealers themselves would love full transparency on private sales in the sector.

But an accounting of galleries’ annual costs would be illuminating, too. Traditionally, McAndrew’s annual surveys have elicited a few data points on this subject (though the catches above obviously remain). For example, the 2021 and 2022 editions of “The Art Market” presented galleries’ costs for internal budget items like mortgage and rent, payroll, fairs, travel, and more. The caveat? The data was measured as a percentage of total annual cost, not in monetary terms (think: dollar value).

“Dealers don’t really like to answer detailed financial questions,” McAndrew said via email. “Sales are one thing, but… asking for detailed info on expenses and cost of sales (which means you can establish profit) is probably too invasive and detailed in my annual surveys.”

She notes that major dealers’ associations regularly conduct “much more specific” surveys of their members that often include detailed data on costs. (She knows because she works on several of those questionnaires.) However, these surveys tend to stay strictly internal to member galleries, with the exception of the lobbyists advocating on their behalf.

McAndrew said that quantifying dealers’ costs “makes it easier to show governments how they operate and get greater understanding of their businesses as part of the service industry, not just as sellers/resellers. Cost info is pretty critical in showing that, actually.” It’s fair to project that it would help enlighten the rest of the industry and the broader public, too, especially in trying to assess when scaling up truly pays off.

2. ART FAIRS AS MIDDLEMEN TO THE MIDDLEMEN

Most costs in the fair sector are just as mysterious as costs in the dealer sector, even as the growth agenda continues driving both to expand. True, two of the biggest fair brands, Art Basel and Frieze, are owned by publicly traded companies (MCH Group and Endeavor, respectively). And yet, since the fairs themselves are only part of these larger entities, it’s nearly impossible for art professionals to extract much of real value from the flood of numbers in their publicly accessible records.

For instance, in the MCH Group annual financial report for 2021, only a handful of macro-level figures are broken down between its “community platforms” (a rubric comprised of the company’s live and digital events) and its other business units (“experience marketing” and venues). Cost and income data on its Individual fairs are subsumed within this larger accounting construct.

In Endeavor’s 2021 year-end report, the financials for Frieze are bundled up with those of its parent company’s related properties (such as the Hyde Park Winter Wonderland, the Ryder Cup golf tournament, and the Miss Universe pageant) into a section labeled “experiences and rights.” So again, we can learn about the operating costs and revenues of the business group, but not of specific constituent events.

In the absence of more precise data, market observers tend to fall back on judging fair organizers’ health by the number of events they stage, the number of exhibitors at each one, and the number of visitors—none of which provides much insight in its raw form. Even the most popular of these metrics, the exhibitor count, offers paltry value since different booth sizes in different fair sections cost dramatically different rates to occupy. (Ticket sales are insignificant to overall results; remember, the exhibitors are the clients paying the bulk of the fairs’ revenues.)

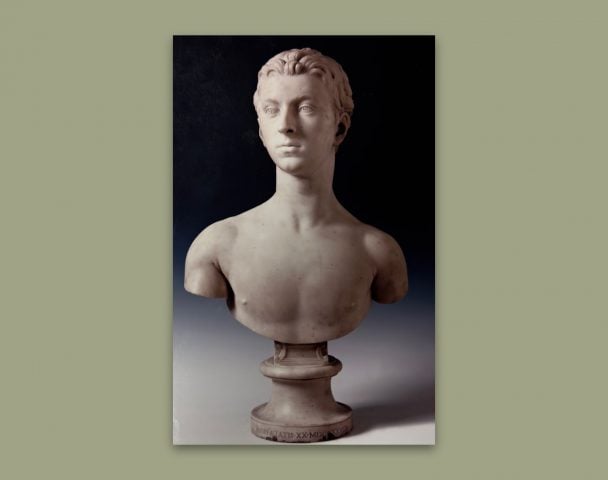

One of the statues from the baptismal font at Siena Cathedral being cleaned with a porcupine quill. Photo courtesy of the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, Florence.

3. COLLECTORS AS CUSTODIANS

If you want to see me react like a cornered wolverine, tell me that owning artwork has proven to be a better investment than owning an S&P 500 index fund or a broad-market ETF. While there are many dimensions to this fallacy, one of the most insidious is a refusal to acknowledge the tangible costs of properly caring for a collection.

Obviously, a buyer’s specific maintenance expenditures will depend on the amount of works they acquire, the mediums of each, as well as how often and where they want to move those works. But after factoring in transport, installation, storage, insurance, and more, building a collection generally demands paying incidentals that amount to a non-negligible percentage of the works’ acquisition price in perpetuity. For a benchmark, Brussels-based collector and investment banker Alain Servais estimates that he shells out between three and five percent per year on average to care for the hundreds of works he owns.

That may not sound like much over the short term, but these carrying costs add up to a sizable sum over the medium and long term. More importantly, they weigh down the allegedly lofty returns on investment (ROIs) for reselling art that are so often used as a marketing tool in trying to grow the art trade’s buyer base.

4. ECOLOGY AS ALL-IMPORTANT

Looming over every sector of the art industry (and every company on the planet) is the environmental cost of doing business, let alone scaling up, at this precarious time in the Anthropocene. The good news is that recent years have seen a small but growing number of climate-centric quantification tools emerge online, including the Gallery Climate Coalition’s carbon calculator. (Incidentally, a guiding light of the GCC’s policies is Oxford economist Kate Raworth, who was heavily influenced by Herman Daly’s work on steady-state economics.) More and more targeted research on the art trade’s ecological impact is also on the way.

However, the industry still has a long way to go in even expressing its climate toll in meaningful numbers, let alone actually adopting greener operations. McAndrew, for one, has a report in the works on the ecological costs of a few focused areas of the art business. “We do need much better, practical tools to guide the industry,” she said. “I can hopefully try and say what’s happening with things like trade and travel, but the real cost of that and, more importantly, what do we do from there is the hard part.”

Still, the first two steps in every solution are recognizing that a problem exists, then getting a sense of just how severe it is. Collecting genuinely valuable data on the art industry will help us take those vital first steps across sectors. But ignoring the unhelpful data, no matter how convenient or how prevalent it has become, will be just as important.

[The New York Times Magazine]

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: The more universally an idea is accepted in these broken times, the more suspiciously it should be viewed.