The Art Detective is a weekly column by Katya Kazakina for Artnet News Pro that lifts the curtain on what’s really going on in the art market.

When the telecom billionaire Patrick Drahi bought Sotheby’s two years ago, a lot was made of the seemingly excessive $3.7 billion price he paid to take the storied auction house private. Employees held their breath in anticipation of dramatic belt-tightening by their new Franco-Israeli owner, dubbed the “cost killer” by the French press.

Then, the pandemic hit. Concerns about cutbacks were overshadowed by an existential threat as countries went into lockdown and the human toll soared.

But as it turns out, the ongoing health crisis has been good for the 277-year-old auction house. Really good. And now, its owner is considering cashing in.

Drahi was able to slash costs—straight out of his playbook—under the veil of Covid-19. At another time, there may have been an outcry. But in the spring of 2020, countless businesses were making similar choices to survive.

Drahi and his team, led by CEO Charles Stewart, were also able to take advantage of the technological innovation built up by the previous management, pivoting seamlessly into the digital age of livestreamed events and online-only sales. By mid-May 2020, just two months into lockdown, Sotheby’s had sold $100 million in art and collectibles online. This year, the company’s online sales reached a mind-boggling $800 million.

Last week, Sotheby’s announced a record $7.3 billion in annual sales, up 71 percent from 2020. That same day, Bloomberg News reported that Drahi is contemplating re-listing Sotheby’s as a public company, presumably to raise capital for other ventures or walk away with a profit in record time.

“If he takes it public, it will be a triumph of what a talented entrepreneur can do in the private setting when he has the ability to do it,” said Tad Smith, Sotheby’s former CEO, who was instrumental in selling the company to Drahi. “It would be such an amazing example of shareholder value creation, it’s almost irresistible.”

Sotheby’s at the New York Stock Exchange. Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s.

In It for the Long Haul or Just ‘Five Minutes’?

There have been whispers about a possible IPO from day one under Drahi, even though the new owner told employees that the acquisition was about his legacy and that one day it would be run by his children, according to several people familiar with private meetings. Nathan Drahi, the billionaire’s son, was named managing director of Sotheby’s Asia earlier this year.

When asked about the IPO, a Sotheby’s spokeswoman said the company doesn’t “comment on rumors or speculation.” Employees were alerted to the Bloomberg article and told there’s nothing behind the rumor.

“On the face of it, given the year we had, it would be the moment to do it,” said one puzzled staffer, who asked not to be named because they were not authorized to speak to the press. “But he only owned it for five minutes.”

An IPO would give Drahi access to a good chunk of cash just as he’s beefing up his majority stake in the British telecom giant BT. It may also help plug the losses at Altice USA, the American telecom branch of Drahi’s empire, whose shares are down about 58 percent year-to-date as cable customers convert to streaming services in droves.

While private, Sotheby’s could restructure without scrutiny; if it returns to the public market, it would have ample access to capital to pursue growth as a transformed business.

“Given that they made record profits, great guarantees, cut costs everywhere, staff reductions—it’s the perfect time to sell with a record year as next year might not be so good,” said Philip Hoffman, chief executive officer of the Fine Art Group, an art finance and advisory firm.

Drahi would be able to retain control over Sotheby’s by listing a minority percentage of the company, according to investment banker and strategist Lisbeth Barron. Companies typically list 15 percent or 25 percent initially, she said. (Sotheby’s minority shareholder is financier Alex Klabin, who, sources said, invested about $100 million in the company last year.)

“Strong companies that are leaders and have recognizable brand names, like Sotheby’s, are always going to be welcome in the IPO setting,” said Barron, a 35-year Wall Street veteran and CEO of Barron International Group.

This year has seen record levels of IPO activity, with 2,388 deals and $453 billion in global proceeds, Barron noted, citing Ernst & Young research. The fourth quarter alone has seen the highest activity rate in the IPO sector since 2007. Institutional investors have a lot of money to put to work, especially before the Federal Reserve raises interest rates next year.

“Going sooner is prudent,” Barron said. “The pricing is very attractive right now to an issuer versus where the markets may be in the next six months. They are able to get premium valuations.”

Welcome to the metaverse. Courtesy of Sotheby’s Twitter.

‘The Cost Cutter’ in Action

Sotheby’s would return to the stock exchange a streamlined operation. The company furloughed 12 percent of staff in April 2020, additionally laying off scores of people in the U.K. and Europe, cutting salaries, and delaying bonuses and equity payouts.

Under CEO Stewart, most of the existing C-suite was gone before lockdowns even went into effect. The remaining senior executives were offered salary cuts in exchange for equity down the line, a common practice at tech start-ups, according to people familiar with the talks. New hires and investments spearheaded by Stewart were laser focused on technology (live-streaming, a new mobile app, NFT infrastructure).

The scale of the cuts could be gleaned in last year’s audited report concerning Drahi’s $119 million debt burden related to the acquisition of Sotheby’s. Deloitte auditors forecasted “significant cost savings in excess of $100 million when compared to the prior year.”

Some changes happened organically: travel, entertainment, publishing, and marketing budgets plummeted as people stopped going out. No one blinked when Sotheby’s switched to digital catalogues (in fact, Christie’s soon followed suit).

Other steps to leverage the company’s assets were expertly engineered by Drahi’s team. Last year, Sotheby’s implemented a new fee, an “overhead premium” equivalent to 1 percent of the hammer price. (Christie’s and Phillips don’t have that fee.)

With no patience for diva behavior, current and former staffers said, Drahi opted to replace executive rainmakers with, presumably, less expensive leaders. “In their view, the brand is bigger than people,” a former employee said.

No stone was left unturned. For example, sellers used to be paid in 35 days. Under the new management, that quickly changed to 35 business days and has now been extended to 45 days. Meanwhile, buyers still have to pay by day 30—which means that Sotheby’s owner can put hundreds of millions of dollars to work for him for 15 extra days before paying out.

Helena Newman at Sotheby’s on October 21, 2020 in London, England. Photo by Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Sotheby’s.

Real-Estate Machinations

Real estate has also been key to generating cash flow. During the due diligence period prior to Drahi’s acquisition, his team requested a list of Sotheby’s leases. One of those was the office of Sotheby’s France, located on the prestigious Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, across from the presidential Élysée Palace.

“He was mystified that we would lease,” said a person familiar with the talks. In December 2020, Sotheby’s announced the acquisition of a building nearby, the former home of legendary Impressionist gallery Bernheim-Jeune.

By owning such buildings, Drahi adds more assets to his ledger that can appreciate—while at the same time extracting cash through mortgaging or refinancing. Sotheby’s also recently acquired a residential real-estate company, Concierge Auctions.

Last month, the Telegraph reported how Drahi profited from buying Sotheby’s home since 1917 in London for £230 million, then leasing it back to the company. The maneuver allowed Drahi to take a £450 million loan and get a £100 million dividend through a chain of companies, according to the Telegraph.

“He leverages every asset,” a former employee said.

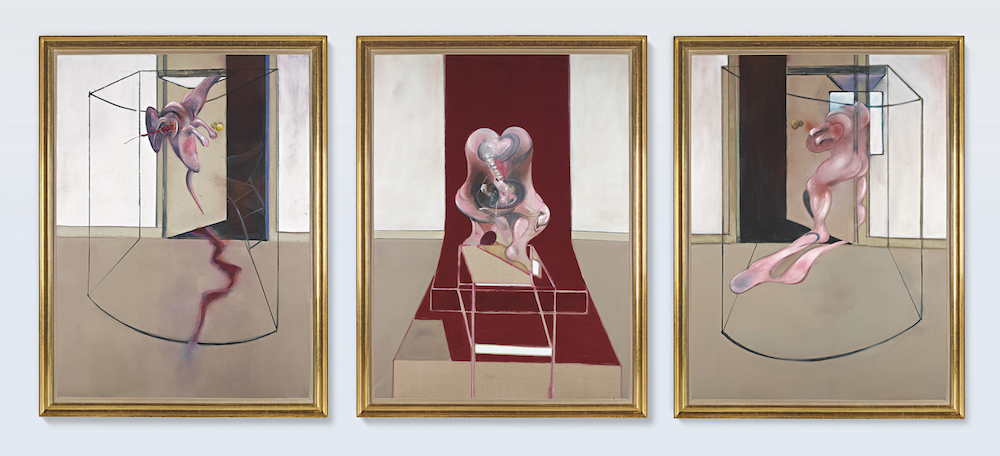

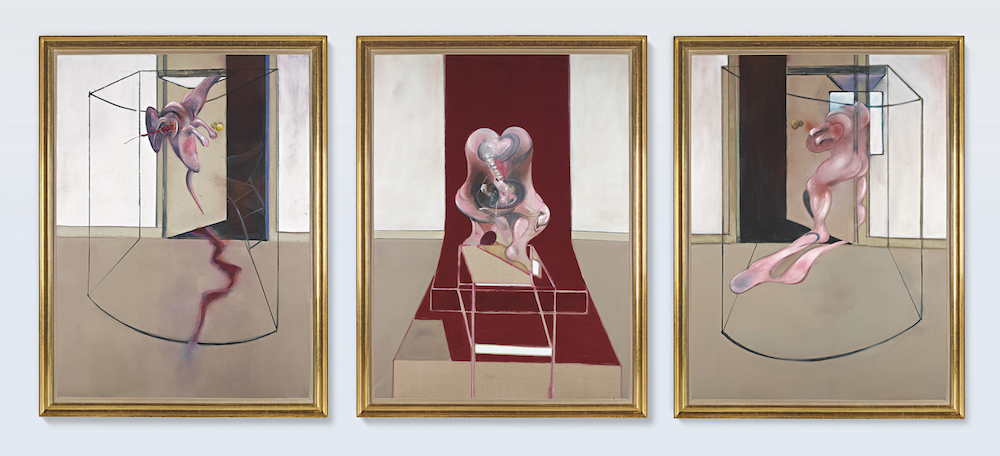

Francis Bacon, Triptych Inspired by the Oresteia of Aeschylus (1981). Image courtesy of Sotheby’s

What’s Next

Auction veterans know that theirs is a fickle business. But in 2021, they actually made money, executives said. Both Christie’s and Sotheby’s lost millions on bad guarantees in 2015, the most recent market high, when global auction sales reached $29.3 billion, according to the UBS annual art market report. Since then, the companies have gotten smarter about outsourcing their risk to third parties. In November, more than two-thirds of the total value of New York’s evening auctions was pre-sold through guarantees, many of which had irrevocable bids attached, according to ArtTactic.

Sotheby’s won the Macklowe collection thanks to a big guarantee to the octogenarian divorcées Harry and Linda Macklowe. Word in the market is that it was $100 million more than Christie’s offered. The bet seems to have paid off: the collection generated $676 million in sales even before the second batch comes up in May.

This year also saw a tremendous influx of new buyers, and Sotheby’s was there to lure them in with emerging art, $1.5 million Nike sneakers, NFTs, and ability to pay in cryptocurrency.

“I’ve been in this business for 20 years,” said Gregoire Billault, the company’s chairman of contemporary art. “It’s not that we are doing 10 percent or 20 percent better. It’s just another company.”

Some experts point out that Drahi as a collector is in an acquiring phase, similar to the posture of Christie’s owner Francois Pinault in the early 2000s. Last year, for example, Drahi was the winner of Francis Bacon’s Triptych Inspired by the Oresteia of Aeschylus (1981), which fetched $84.6 million, according to people familiar with the sale. It was Sotheby’s top lot of 2020.

He may end up owning the painting longer than the auction house where he bought it.