The Appraisal

Surrealist Artist Francis Picabia Was the Ultimate Shapeshifter. Did All That Experimentation Stunt His Market?

Despite his reputation as an artist's artist, demand for works by Francis Picabia trails that of his Surrealist peers.

Despite his reputation as an artist's artist, demand for works by Francis Picabia trails that of his Surrealist peers.

Julia Halperin

Surrealism is having a moment. From the Tate’s international survey to the stacked lineup of Surrealist artists in the central exhibition of the 59th Venice Biennale, the early 20th-century movement is taking on new significance for artists and curators alike.

On the market side, some recalibration is happening as well. Last week, Sotheby’s held its first-ever Surrealism auction in Paris, led by a record-setting Francis Picabia painting. Pavonia (1929) fetched $10.9 million (€10 million), surpassing the late artist’s previous high of $8.8 million, set in 2013.

The legendary dealer Léonce Rosenberg commissioned Picabia to create Pavonia for his Paris apartment (specifically, Rosenberg’s wife’s bedroom). It was the central panel in a grouping from Picabia’s “Transparences” series, for which the artist deployed overlapping imagery to cinematic effect.

On the heels of this headline-making sale, we dug into the Artnet Price Database to see how the protean artist’s market has evolved over the years—and where it may go from here.

Auction Record: $10.9 million for Pavonia (1929), at Sotheby’s Paris in March 2022

Picabia’s Performance in 2021

Lots sold: 48

Bought in: 17

Sell-through rate: 65 percent

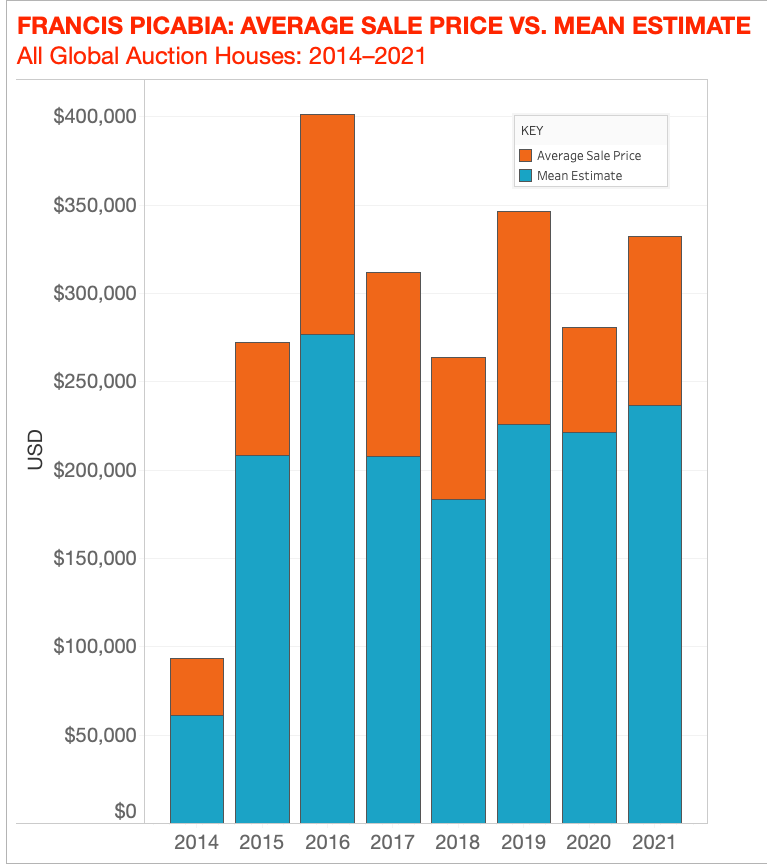

Average sale price: $332,302

Mean estimate: $236,391

Total sales: $16 million

Top painting price: $2.3 million

Lowest painting price: $19,000

Lowest overall price: $439, for a small stencil print from an edition of 300

© 2022 Artnet Worldwide Corporation.

Over the course of his decorated career, Picabia—who was born wealthy and gained a reputation as a jokester and a playboy—hopped from Impressionism to Cubism to Dadaism, even dabbling at one point in Renaissance-style painting. His heterogenous approach earned him admirers in his own time and beyond, but has hampered his appeal in the art market, which prefers clear brands and easy definitions.

Some sources say Picabia’s protean style also makes it more difficult to identify fakes, while his penchant for reusing old canvases and incorporating earlier material into newer work has made accurately dating objects a particularly daunting task. The Picabia catalogue raisonné is not yet complete, though new volumes were published in 2016 and 2017.

Picabia is a quintessential artist’s artist: Many of his best works are already in museum collections, and his paintings have been collected by the likes of painter Julian Schnabel and Calder Foundation chief Sandy Rower. In recent years, his work has occasionally popped up at art fairs and sold for prices in the high six and (very) low seven figures.

Because of his slippery style, Picabia is unlikely to achieve the same level of market success as Magritte or Miró. But for those who want to own work by an artist who has influenced generations, and whose stature in art history is likely only to grow, Picabia remains a canny choice.