Every Wednesday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, trying to distinguish between a lifeline and a live wire…

EVOLUTION OR DEVOLUTION?

Last week, I started hearing chatter about a new twist in the art world’s crypto-saga: some leaders at major U.S. museums had begun quietly exploring the possibility of selling NFTs of some of their most famous artworks to fundraise after more than a year in shutdown hell. But while the proposition might technically keep institutions clear of the public-relations wildfire that is deaccessioning, this alternative route might actually lead them straight into an even worse disaster.

Now, there is a lot going on in this thought experiment, so let’s begin with the tech side. If you’re still only in the shallow end of the crypto pool, it might be a little jarring wrapping your head around a non-fungible token for a physical object. After all, the nitroglycerine in 2021’s NFT explosion has largely been digital media. But an NFT is really just a claim ticket to an asset (meaning, an artwork). And while the NFT lives on the blockchain, the asset could be physical.

This isn’t a brand new idea. Between about 2014 and 2018, a number of startups emerged that were primarily dedicated to creating on-chain title registries for old school, off-chain art like paintings and sculptures. (It was a whole thing. A few of them have kept on keeping on.)

But if there was any in-depth discussion about the idea of monetizing NFTs for works in institutional collections at the time, it got nowhere near the mainstream. I suspect that’s because there wasn’t much demand for even the for-profit use cases, let alone something else.

Then 2021 started. Yes, NFT prices are still wavy, the overwhelming majority of the money is still going to a select few artists, and most of the tokens ringing up thunderous prices still correspond to strictly digital assets.

But there is some real demand for NFTs certifying ownership of physical assets. For example, of the 10 tokens designer Andrés Reisinger sold in minutes for $450,000 this February, five were to validate tangible pieces of to-be-fabricated furniture. The cocktail of real desire and real wealth can make anything possible almost overnight in every market. So why not museum-sanctioned NFTs of some of history’s greatest artworks?

Emanuel Leutze, Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

LAW AND ORDER

Since the pure tech side of museum-collection NFTs is feasible, the next questions to explore are whether they would be feasible from a legal, regulatory, and governance standpoint. The short answer appears to be “yes” as long as certain conditions are met.

In the simplest and most lucrative version, the actual painting or sculpture would first need to be owned free and clear by the museum. But if it isn’t old enough to be in the public domain, leadership would need to secure permission from the artist’s estate to mint and sell the NFT. Doing so would be delicate, complicated, and probably not cheap; due diligence, negotiation, and compliance take real resources. But you don’t need to be Isaac Asimov to be able to imagine a world where it happens.

In fact, museums actually navigate a lot of these rapids just to sell posters and coffee mugs emblazoned with their most famous paintings. Setting aside philosophy and ethics for the moment, an NFT of, say, Starry Night would be just another avenue for MoMA to monetize the work without upending the underlying property rights: the Fondation Vincent Van Gogh retains control of the copyright, and the museum retains controlling ownership of the object.

“Controlling ownership” is key here. The only scenario in which plutocrats might get fat-check excited about an NFT is if it certifies a claim to the actual artwork, not some “unique” digital reproduction of it. But it can’t be a majority claim, either, or else the buyer would have legal grounds to march in like Darth Vader with a shock force of art handlers and grab Starry Night off the wall to take home.

This means any museum NFT would only confer minority ownership of the work. This is not actually as foreign as it sounds, because U.S. museums have been accepting so-called partial gifts for generations.

In this structure, donors agree to transfer, say, 10 percent ownership of a painting to an institution every year for a decade, with proportional tax benefits along the way; at the end of this span, the work fully enters the collection. To ground the benefits in reality, if you’ve ever marveled at the 53 Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works comprising the Met’s Annenberg Collection, or sunk into Paul Cézanne’s Boy in a Red Vest at MoMA, you can thank partial gifts for the experience. The same can be said for hundreds of other bravura pieces at institutions around the country.

To my understanding, museums could essentially invert the regulatory and governance principles that enable them to accept partial gifts to sell partial ownership of works in the collection via NFTs. On the surface, then, it seems like this strategy might be the best of both worlds for cash-strapped institutions: all the financial benefits of deaccessioning, but without actually losing control of the painting.

There is one big caveat, though. In theory, every one percent of fractional ownership translates to the right for the recipient to actually possess the piece for the same percent of the calendar year, meaning, 10 percent ownership equals 36 annual days of control. But in practice, museums have usually been content to let fractionally gifted works stay with the donor until the deal’s conclusion.

I suspect institutions would want to build on that convention by structuring the (smart) contract so that an NFT’s buyer acquires no right to partial possession of the underlying piece—ever. Even the risks of schlepping Starry Night a few blocks north to a Billionaires Row penthouse for 36 days a year are too high for a museum board to stomach. Forget about selling two percent ownership to an Emirati royal and having to slide one of civilization’s greatest artistic achievements onto a private jet for an annual one-week trip.

Could this detail be a dealbreaker? Well, that’s the first of what I see as the vital questions about this concept’s ultimate value to struggling museums.

Monet’s Water Lilies at MoMA, 2019. (Photo by Kena Betancur/VIEWpress)

“COULD” VS. “SHOULD”

Since so much of the NFT boom is being driven by the allure of intangible bragging rights, not the possession of objects, my hunch is that demand for the tokens would not be affected much if patrons understood the underlying masterpieces would stay locked inside the institutions forever. But other factors might, in the eyes of New York University’s David Yermack, an organizational economist who has done pathbreaking work on both museum governance and crypto.

“I think demand for NFTs is driven by tech-savvy people,” he said. “They may not appreciate an Old Master painting in the same way as an 80-year-old billionaire would.”

Anecdotal evidence supports Yermack. It isn’t just that the bulk of top-selling NFTs correspond to digital-only assets. It’s also that the artists on the receiving end of all that crypto-wealth have generally built careers entirely outside the artistic establishment.

When Christie’s decided to auction its first NFT, it didn’t latch onto Damien Hirst’s forthcoming blockchain opus; it partnered with Beeple, whose name carried about as much weight with traditional mega-collectors as mine would at Buckingham Palace. Yet that choice rewarded the house with a $69 million milestone. I think every art lover (myself included) should level with themselves about the very real possibility that Beeple may mean more to the crypto-wealthy than Vincent van Gogh.

Another important factor pumping up profits in the NFT market is the economy of fame. Demand has propelled tokens of a LeBron James highlight video to $208,000; Twitter founder Jack Dorsey’s first tweet to $2.9 million; and whistleblower Edward Snowden’s photomontage self-portrait to $5.4 million, to name just a few. Christie’s next big NFT sale on May 14 centers on a backstory-rich photo of model and collector Emily Ratajkowski. There’s no guarantee that an NFT for what we, in the niche-within-a-niche art world, consider to be masterpieces would bring a similar windfall to the museums that own the paintings.

But I agree with Yermack that the uncertainty shouldn’t hold back an institution that feels compelled to find out this way. “My advice to museums would be to give it a whirl, and see if you can develop a market—but do it quickly.” Despite some recent turbulence, crypto is still having a moment, and that moment may be fleeting.

Yet there’s more to the equation than just economics and timing, too. Amy Whitaker, a professor of visual arts administration at NYU who began researching blockchain in 2014, told me she has been informally approached by museums about how they might leverage NFTs. Her opinion is that deaccessioning is actually a less fraught option than crypto-fundraising from works still held by an institution.

“I can see how the latter looks like free money to people, but it’s kind of like fracking your collection: there are a lot of knock-on or second-order effects that are hard to think through ahead of time,” she said.

One institutional curator who works with digital art echoed Whitaker’s thoughts. They felt that the entire meaning of “stewardship”—one of the responsibilities forming the nucleus of any museum—would need to be rethought in order to coexist with NFTs of institution-owned pieces. (By the way, they too had heard chatter about museum leaders exploring the prospect of trying this.)

Basically, the point is that it’s fine to relinquish your stewardship entirely through (rulebook-observant) deaccessioning, and it’s fine to hawk gift-shop reproductions of a work you’re still caring for. But it’s something else entirely to monetize the actual work while it keeps hanging on the gallery walls.

In other words, instead of being the best of both worlds, this scheme might actually be the worst one yet. So where does that leave us?

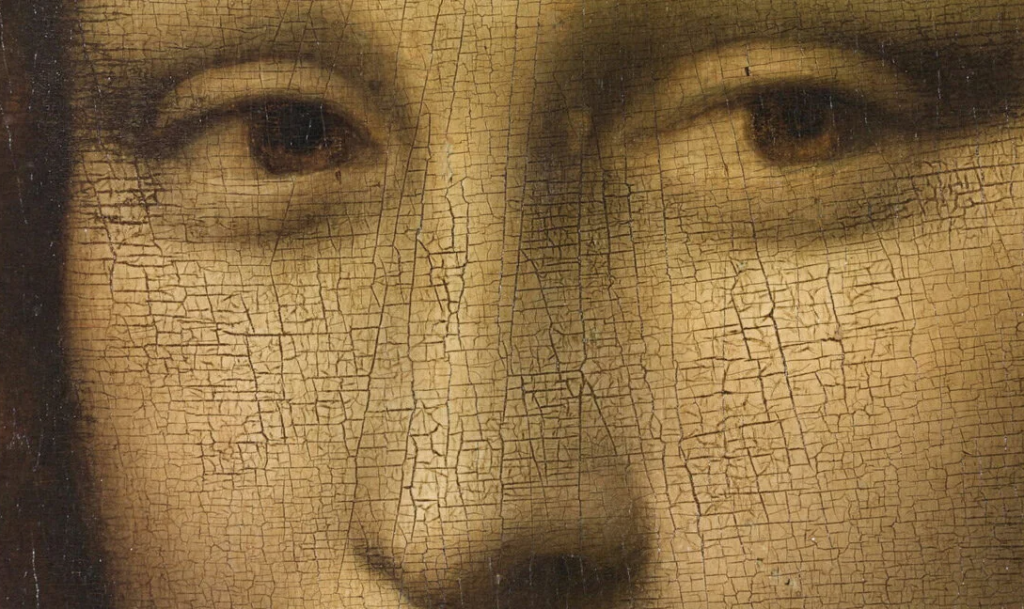

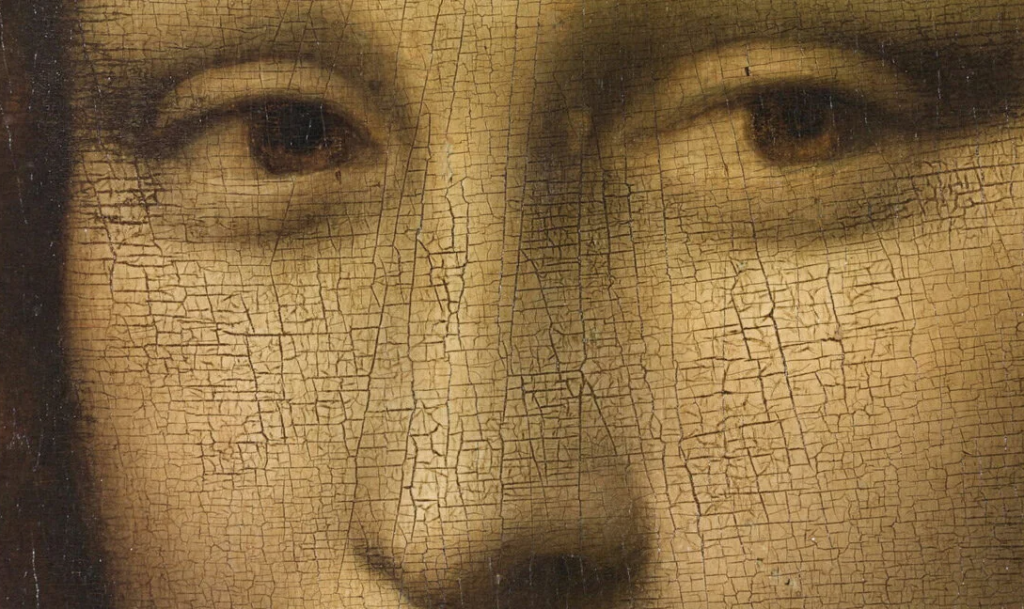

A high-resolution detail of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Courtesy of the Musée du Louvre.

BREAKING AWAY

To me, the most salient point of all is the only one on which all the people I spoke to agreed. Even Yermack, who adopted the most supportive stance on museum-offered NFTs, still saw them as insufficient to rescue U.S. museums from the historic crisis they’re now enduring. In the best case, NFTs still probably won’t raise truly difference-making money from the people who care most about art institutions, yet they’re guaranteed to magnetize at least as much controversy as deaccessioning.

But to me, instead of shrinking back to the status quo, we need to think bigger. Museums are not just under duress from an external catastrophe. They are also suffering from structural problems in fundraising, governance, and even discourse that have been intensifying for decades.

Yermack, who has published influential studies of board governance as far back as the ’90s, argued that “nonprofit boards are very often dysfunctional, and never more than in art museums.” Research has found that, across industries and across the for-profit/nonprofit divide, the most effective organizations are led by boards that top out at less than 10 seats. Most nonprofit boards, however, typically count 50 to 100 trustees, which makes them “not really boards at all, just incubators for potential donors.” If the hollowed-out budgets from this past year’s crisis haven’t called into question how well those incubators are working, I don’t know what would.

Whitaker also thinks museums need to be vastly more transparent about their operations. Inside, they may be mostly white cubes, but from outside they mostly remain black boxes. The public only hears about budget shortfalls, attendance numbers, and whether ticket prices are going up. But what does it mean for museumgoers if an institution has to spend 70 percent of its unrestricted funds to keep staff employed during an epic lockdown? What is the institution doing day-in, day-out to represent the community and engage its needs outside of its programming?

As Whitaker put it, “You figure out in a crisis how much good will you’ve generated.” Personally, I haven’t seen a lot of people leaving care packages at museums’ front entrances during the past 13 months, and I think that means something.

And finally, yes, there’s deaccessioning. I think there’s tremendous merit to doing it on a much grander scale. But details of that expansion matter too, and it seems impossible to have a conversation about what they could be without instantly being dragged into a no-holds-barred flame war.

Would it really be a crime against nature if deaccessioning proceeds were expressly put toward the endowment, or paying museum staff a living wage? What if a museum director thinking laterally about deaccessioning weren’t automatically assumed to be a soulless bureaucrat who can’t wait to sell every painting with a healthy appraisal to stock up on toilet paper and pre-pay 12 years of HVAC bills? And what if “serving the public trust” could actually mean something more community-focused than clutching onto a massive art collection as it plunges an institution, its staff, and its rank-and-file visitors over a financial cliff?

I’m not saying I have the answers. But I am saying we need to start from square one to try to find them, beginning with the acknowledgments that museums have a hard job to do, and those of us who care about them should have more in common with each other than the current debate positions us to recognize.

One thing I’m sure of, though, is that issuing NFTs won’t save museums. And the more time we spend looking at them, the less time we spend looking at other big ideas that might.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: the main thing is to keep the main thing the main thing.