Opinion

From Mona Lisa’s Secret Number to Duchamp’s Hidden Face: 5 Conspiracy Theories That Will Blow Up Your Art World

Did Duchamp lie about finding his readymades? Did Anthony Quinn's painting predict 9/11? The truth is art there.

Did Duchamp lie about finding his readymades? Did Anthony Quinn's painting predict 9/11? The truth is art there.

Ben Davis

In a lot of ways, this was the Year of the Conspiracy Theory. Fabulations and connect-the-dots conjectures of all sorts found their way from the margins to the center. The phenomenon very much affects art—which makes some sense, in that art is designed as fodder for fantasizing.

Most of the time, such speculation is as consequential as the latest theory about Game of Thrones, playing the same function of agitating the imaginations of superfans. Thus, a great deal of the hype around Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi earlier this year was driven by amateur speculation about its symbolism.

Every so often, art conspiracy crosses over into much more sinister territory, as in last year’s contrived freak out that a Marina Abramovic “Spirit Cooking” performance proved, through circuitous logic, that Hillary Clinton was in league with Satan.

Either way, it’s worth at least keeping these things in the corner of one’s eye. Here are five of the wilder art theories that floated to our attention this year.

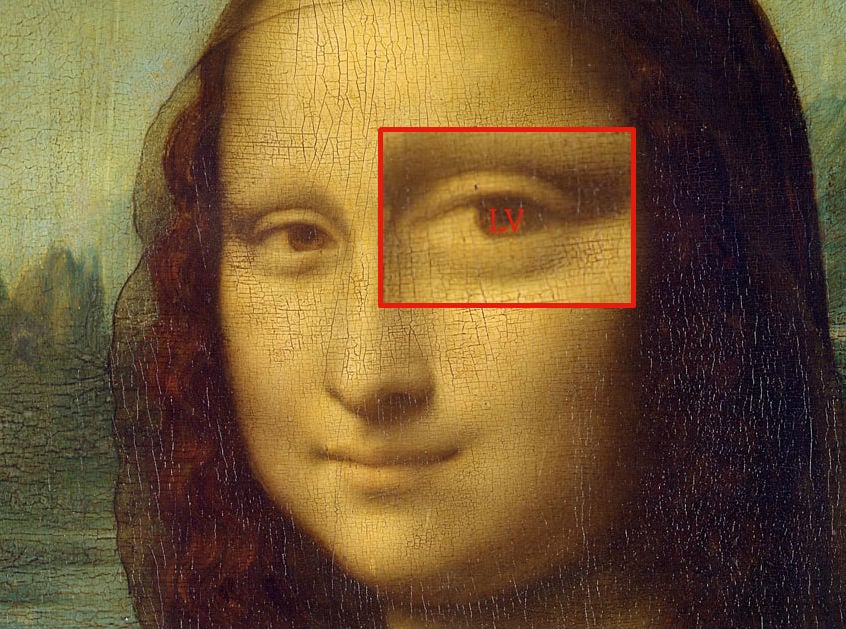

Pavel Floresco demonstrates the significance of the number 2 in Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa.

You could write an entire book just about conspiracy theories relating to Leonardo da Vinci and his most famous painting, the Mona Lisa. A new one to come across our radar this year came courtesy one Pavel Floresco. Disputing that the painting is a simple portrait of Lisa del Giocondo, Floresco declares that “[e]verything comes to confirm Sigmund Freud’s conclusion: this masterpiece represents the mother of the artist, Caterina, seen as an ideal of the maternity or femininity.”

How to prove this theory? It’s a bit complicated, so let’s take it step by step. First, Floresco creates an alpha-numeric correspondence between various numbers and the letters of the Italian alphabet, like so:

A = 1 B = 2 C=3 D = 4 E = 5 F = 6 G = 7 H = 8 I = 9 L = 10 M = 11 N = 12 O = 13 P = 14 Q = 15 R = 16 S = 17 T = 18 U = 19 V = 20 Z = 21

He then reduces the names “Mona Lisa” and “Catarina” into numbers, and adds them up. For “Mona Lisa,” the operation looks like this:

MONA LISA = 11 + 13 + 12 + 1 + 10 + 9 + 17 + 1 = 74

He then takes the two numbers in “74,” and adds these up:

7 + 4 = 11

At last, he takes the two digits of the resulting “11” and adds them up again—revealing the secret number 2 hidden in the Mona Lisa:

1 + 1 = 2

Repeat the same operation with the name of Leonardo’s mother, “Caterina,” and, chillingly, you get the same result:

CATERINA = 3 + 1 + 18 + 5 + 16 + 9 + 12 + 1 = 65

6 + 5 = 11

1 + 1 = 2

Of course, the name “Mona Lisa” is a nickname derived from Vasari; the painting’s first owner seems to have referred to it as La Gioconda. But Floresco offers more: To illustrate the significance of the number 2 in the canvas, Floresco breaks down the symbolism of the painting: 2 columns in the background; a road in the landscape in the shape of the number 2; a hand flipping the number 2… (She even has 2 eyes and 2 nostrils!)

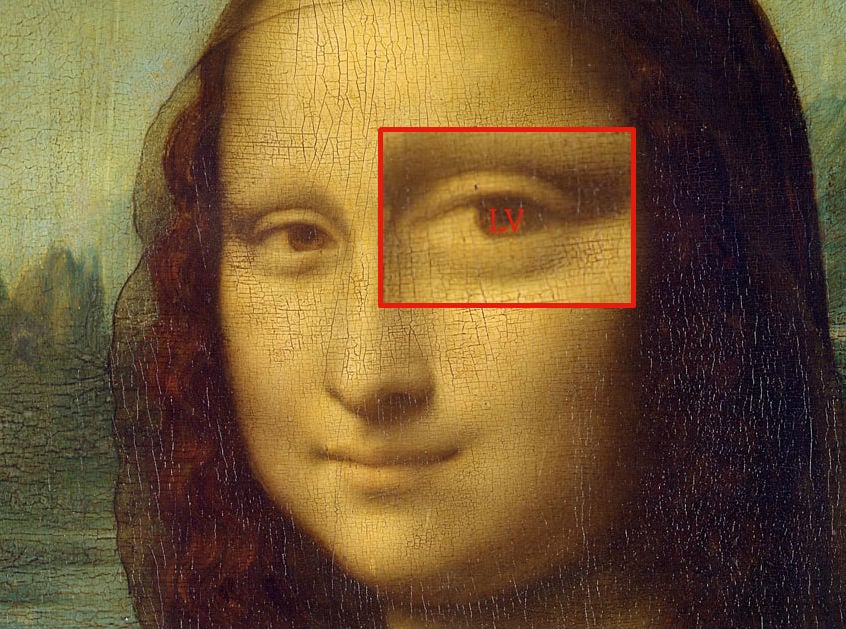

But there’s more proof still. Floresco also shows that the 2010 discovery (heretofore considered dubious) that the Mona Lisa’s eyes concealed the hidden letters “LV” and “CE” can be explained: Those initials, too, yield up the all-important 2.

LVCE = 10 + 20 + 3 + 5 = 38

3 + 8 = 11

1 + 1 = 2

How deep does this thing go? If you find out, it might be wise 2 keep it 2 yourself…

Albrecht Dürer, The Four Apostles (1526). Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Anyone who has had to search the Internet for information about Albrecht Dürer, pillar of the German Renaissance, will have come across the Albrecht Dürer Blog. The result of the labors of amateur art historian Elizabeth Garner, a collector of Dürer prints, the site posits a cryptic series of coded messages hidden throughout the master’s work that reveal him to have been, secretly, a Jewish rebel bent on annihilating his Christian patrons.

In a 2011 interview with the Connecticut Jewish Ledger, Garner explained the genesis of her theories. It all began when she discovered a secret message in the Dürer print The Promenade (ca. 1498). This led her down the rabbit hole, discovering allusions to Judaism everywhere in the oeuvre of the putatively Christian artist, with world-historical significance: “I am now of the belief that the Holocaust couldn’t have happened as it did,” she said, “were it not for the truth of the whole Dürer story.”

Dürer’s hometown of Nuremberg officially issued its order to expel its Jewish population in 1499. As Garner explains:

The Dürer family knew they couldn’t stop the expulsion of the Jews, and they even knew that their true history was going to be erased. How to survive? Encode the story in the art, for that was their only weapon, and their only chance to get the truth to survive. Except you had to be very careful, and they were. “The Dürer Cipher” breaks down into a Memorbuch [memory book] and revenge upon the villains. The Durers, Jews, won, because Dürer’s art has baffled all—until now.

Garner has continued to develop these theories, including a very lengthy disquisition on penises (“Let’s get real and talk about Dürer’s penis for it is a very important penis indeed”).

Most spectacularly, she now asserts that Dürer’s revenge went beyond encoding secret Jewish references in his painting. While remaining undercover, he actually deployed poisonous pigments in his works, both as a way to punish anyone who tried to tamper with his secret messages, and more generally just to slowly destroy his Christian patrons.

“Notice that these paintings are almost all lead white, vermilions, green, orpiment, and black,” Garner and co-author Joe Kiernan note of the German artist’s Four Apostles, which he gave to the city fathers of Nuremberg. “Albrecht really wanted to take revenge on the whole government, the CITY COUNCIL, where every day they would be inhaling the noxious fumes. He even donated them! and got paid for his work!”

George Charles Beresford, portrait of Walter Sickert (1911). Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

What Dan Brown is to Leonardo conspiracy theories, American crime novelist Patricia Cornwall is to the theory that Victorian serial killer Jack the Ripper was actually British painter Walter Sickert (1860–1942) who was, as his Tate biography put it, “universally acknowledged throughout his life as a colourful, charming and fascinating character, a catalyst for progress and modernity.”

Cornwall claims to have spent well over $6 million of her own money attempting to confirm the theory, and has written two books on the subject. Earlier this year, she told the Telegraph:

Over the past five years I’ve spent thousands of hours as well as another small fortune investing in Sickert’s art, memorabilia and more importantly, other original documents, evidence and technologies.

I’ve continued working with top scientists and art experts, sifting through piles of archival materials, utilising non-destructive forensic paper analysis and special light sources. The upshot is I’ve never been surer of Sickert’s guilt. I believe he was responsible for the Jack the Ripper crimes and other debaucheries as well that include dismemberment, cannibalism, and the murder and mutilation of children.

In 2013, she even purchased, and then destroyed, a Sickert painting looking for clues.

Cornwall’s speculations have been greeted with a collective facepalm by art historians. “[I]n her desire to find answers, she simply hasn’t followed very sound principles of investigation,” Matthew Sturgis, author of a 2011 Sickert biography, told the Independent. “It is a nonsensical misreading of the facts.”

Serkan Özkaya’s We Will Wait (detail) (2017). Photo illustration by Brett Beyer and Lal Bahcecioglu. 2017.

Marcel Duchamp loved games and secrets. He famously said he quit art to play chess, concealing from the world that he was working in secret. You never know where you stand with the guy.

This willfully inscrutable character has, in turn, made his work fertile ground for speculation of all kinds. Indeed, this year a particularly awesome example surfaced when Turkish artist Serkan Özkaya unveiled a full-scale recreation of Duchamp’s final work, the diorama known as the Étant donnés. Özkaya hypothesizes that the peephole that allows you to look in through a door on the famous tableau was actually meant to function as kind of projector, throwing the image of a Duchamp self-portrait onto the wall. (Critics are mixed on whether they actually see it, but you have to admit, it’s a cool theory.)

“I find it almost insulting to Duchamp to think he never looked at it this way,” the artist told my colleague Brian Boucher. “There’s no way a master of shadows, and optics, and stereography, and projection didn’t look at it this way.”

It’s not the most out-there Duchamp theory, though. In the ‘90s, freelance scholar Rhonda Roland Shearer irritated the art history community—which has sanctified Duchamp’s idea of making art from “readymade” objects as the basis of Conceptualism—with another hypothesis: What if, she asked, the French artist actually sculpted all of his famous found-object sculptures by hand?

“It is not just one case,” Shearer told the Times in 1999. “It’s one thing after another. You start feeling like a fool for taking him at his word. Does this make him more interesting? Absolutely. He has been dead since 1968, but it’s as if he’s alive now, because we have a whole new set of objects.”

Duchamp’s snow shovel (Prelude to a Broken Arm, 1915), for instance, would never function as an actual snow shovel because its handle was square, she says, while the artist’s famed urinal (Fountain, 1917) is “too curvaceous” to have come from the Mott Iron Works, where he said he purchased it.

(Another Duchamp theory, incidentally, holds that the French expat did not actually dream up his most famous readymade, Fountain, and that it is instead actually the work of one Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven.)

Do scholars buy the “hand-made readymade” theory? Not in general. Would it matter? “[I]f she’s right,” the late philosopher and art historian Arthur Danto once told the Times, “I have no interest in Duchamp.”

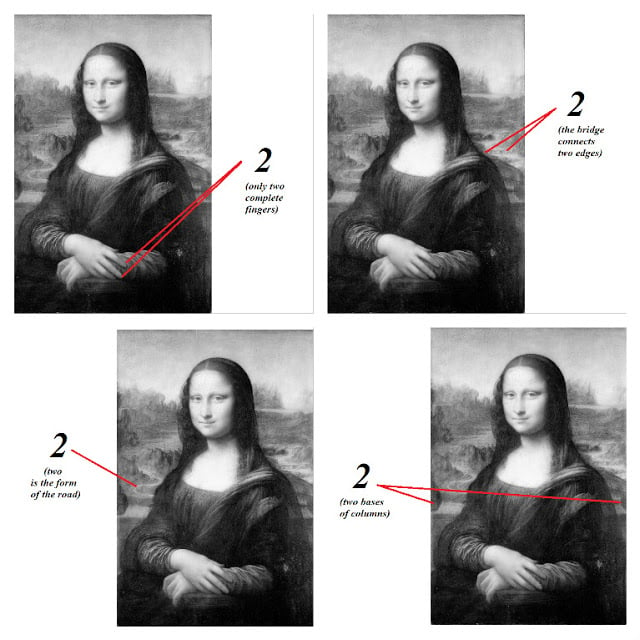

Lithograph of Anthony Quinn’s Facets of Liberty.

Conspiracy theorists have found premonitions of 9/11 everywhere from the writings of Nostradamus to Back to the Future II. This year, add another source to the list: the paintings of the late, beloved Zorba the Greek actor and artist, Anthony Quinn (1915–2001).

Specifically, a book called The Prophetic Imagery of Anthony Quinn, published this year by Quinn’s Maui-based art dealer, Glenn Harte, claims that the actor possessed “precognitive skills.” It points in particular to his 1985 canvas Facets of Liberty as having foretold September 11.

“It was quite a surprise to me, and I kept looking at it and looking at it and seeing more of the images of that day, which included the firemen, the smoke in the sky, the planes crashing into the tower and things like that,” Harte told the Hollywood Reporter. In The Prophetic Imagery of Anthony Quinn, he claims that the painting conceals allusions to both the flaming Twin Towers and a bearded hijacker.

The book gathers proof of Quinn’s psychic powers, including the suggestion that he was visited by the ghost of Paul Gauguin while on the set of the 1956 Van Gogh biopic Lust for Life. In his autobiography, One Man Tango, Quinn claimed that Gauguin’s ghost instructed him on how to hold the paintbrush, resulting in a performance so credible that Quinn won the Best Supporting Actor Oscar.

Among those unconvinced by Harte’s theory of “precognitive painting” is the actor’s widow, Katherine Quinn. She does, however, say that her late husband was haunted by a vision of something terrible shortly before his passing in 2001: “He said something awful is going to happen and nobody even understands on what scale it will be.”