Opinion

Why We Should Reboot the Art History Canon Instead of Ditching It + 2 More Thought-Provoking Things to Read

A weekly round-up of interesting and important readings from around the internet.

A weekly round-up of interesting and important readings from around the internet.

Ben Davis

Each week, countless articles, think pieces, columns, op-eds, features, and manifestos are published online—and any number cast new light on the world of art. Each Friday (when I can!), I pick out a few recent pieces that might inspire some larger discussion.

Here’s an enlightening look at the present round of debates over how art history gets taught. These surged into public consciousness with Yale’s decision to end its popular “Introduction to Art History: Renaissance to the Present” in January over protests that it was Eurocentric, replacing it with looser thematic introductions to subjects like “Art and Politics,” “Global Craft,” “The Silk Road,” and “Sacred Places.”

That controversy was hugely overblown by the centaur-like alliance of anti-intellectual tabloids and canon-worshipping cultural conservatives. In his essay, Petrovich puts the shift into the context of longer-term debates about global art history, talking to a number of people directly engaged with art historical pedagogy.

The opening up of the canon to voices beyond the old-school, Civilisation-style pantheon of Great Men is a fundamentally wholesome, rejuvenating operation. Every new present recreates its own “usable past.” The Victorian era in England found new virtues in Medieval art, and Meiji-era modernization in Japan led to a new appreciation of its own classical arts in “nihonga” painting.

Similarly, so much of what has been exciting in this present moment has been how our own tectonic social shifts have shaken up art history, exposing new layers—for instance, the new interest in the art of the Bombay Progressive painters, the canonization of previously overlooked female spiritual artists like Hilma af Klint, or the revaluation of the art of the Black power movement.

Nell Irvin Painter delivers the ninth annual Shasha Seminar for Human Concerns lecture at Wesleyan. Image courtesy Wesleyan University.

A debate is percolating among the scholars Petrovich talks to, and it’s worth teasing out. On one side are those who favor jettisoning “any claim of comprehensiveness or canonicity”; on the other, there are those who want to hold onto “one of the [college art-history] survey’s abiding goals: establishing shared points of reference.” I think that I agree with the way that historian Nell Irvin Painter puts it: “there is a place for a course in art history without modifiers, but it needs to be global.”

To me it seems important to distinguish between two questions: how art history is taught overall and, specifically, whether there should be a common introductory survey.

One of the scholars Petrovich speaks to jokes that he got into art history “literally to have something to talk about at cocktail parties.” But that’s an important function!

The introductory survey is designed to include both budding art historians and non-art-historians—and that common, bridging space is part of its point. The purpose of art education isn’t just about satisfying your own personal tastes in art; it’s about acquiring a reservoir of metaphors and symbols that allow you to communicate and connect with other people, via images that have been judged to encode historically important knowledge and resonant ways of seeing.

That function can be fodder for cultivating elite snobbery; but it can also provide a language for people from different backgrounds to arrive at shared understandings. (Which is all the more reason for that common foundation to represent different histories in the first place.)

Installation view of “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power” at the Brooklyn Museum. Photo by Jonathan Dorado, courtesy the Brooklyn Museum.

A canon is an arbitrary and provisional construction. Part of the work of art history is figuring out how to renew and rework what’s considered important in light of new understandings of history and the present. That’s what goes on in the non-introductory classes. But without the background idea of a shared body of knowledge that is worth replenishing, that specialist work has less meaning.

This isn’t just a theoretical consideration; it has practical consequences. University humanities departments have been kept alive by the “humanities requirement,” which ultimately depends on the assumption that there is social value in having a baseline of common cultural references, even if you are going into another field.

Already 15 years ago commentators on the “crisis in the humanities” were writing essays arguing that “the rival sides are fighting for a few planks from a ship that has already sunk.” This new round of canon reconsiderations comes at a cataclysmic time for academia—and that’s a cataclysm piled on top of crisis piled on top of decline. If you give up on the idea that it is socially desirable to have “shared points of reference,” it seems to me that you give up on one of the arguments for keeping the humanities in the first place.

It also seems weird to dissolve the idea of common cultural survey at the moment that women and minorities and non-Western cultures enter into the space. Isn’t part of the struggle exactly to make sure that these are part of the common understanding of what it has meant to make art, not just something you can elect to pay attention to?

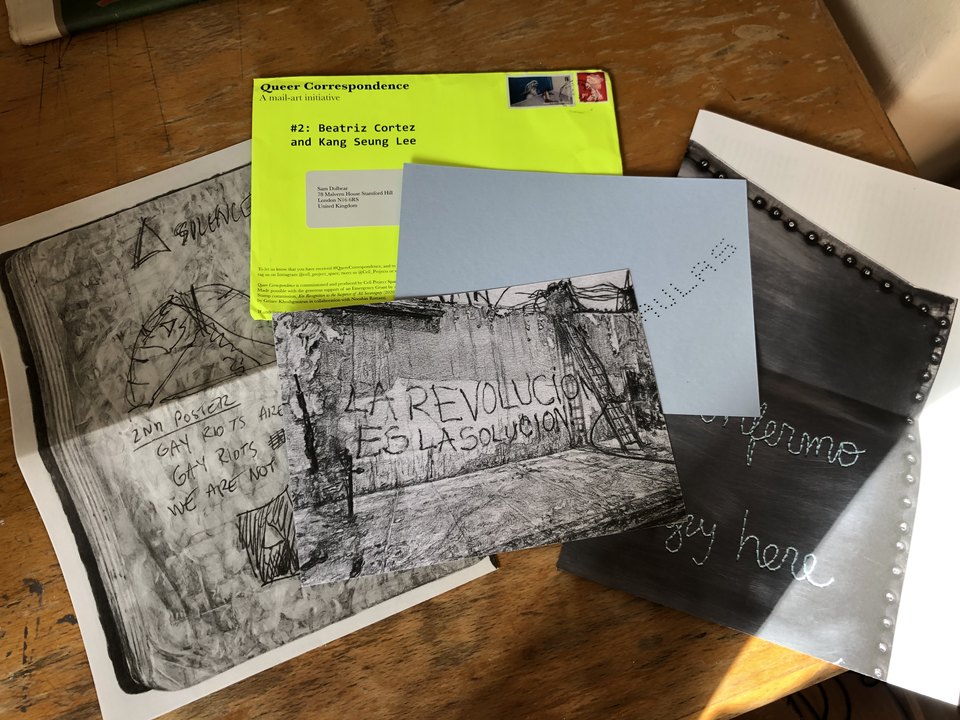

Beatriz Cortez & Kang Seung Lee, Queer Correspondence (2020). Image courtesy Cell Project Space.

London’s Cell Project Space is currently running its “Queer Correspondence” project, a monthly series of new mail-art commissions that mean to “establish connections between queer families,” with the artworks born of the exchanges also mailed out in editions to subscribers. (All 650 editions are subscribed already, though you can get a glimpse of the poetic works sent between Beatriz Cortez and Kang Seung Lee online.) Basciano takes inspiration from the project to survey the particular historical import of correspondence art for LGBT communities, passing from Wallace Berman’s Semina magazine in the ’50s to General Idea’s “Orgasm Energy Chart” of 1970.

“The post office became a place of rescue for misfits and nonconformists,” he writes, which makes sense—a genre that existed on the margins of official ideas of art was of particular importance to the marginalized, not in spite of that fact, but because of it.

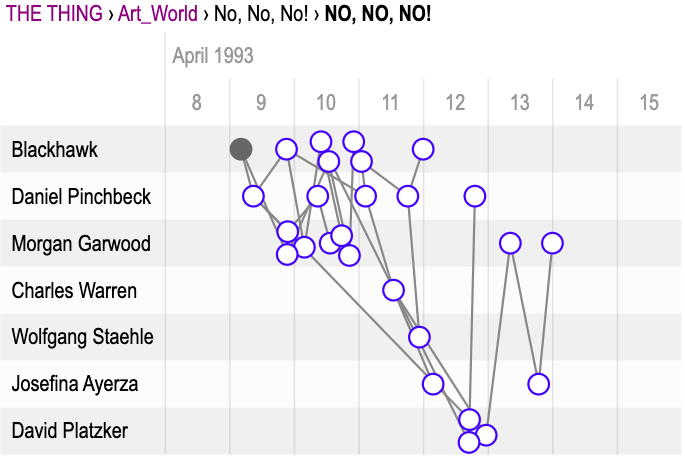

Screenshot showing the conversation timeline fo the thread “NO! NO! NO!” from Rhizome.org’s The Thing archive.

Thanks to a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the web art whizzes at Rhizome are launching an interactive online archive of The Thing, a fondly remembered web bulletin-board system from the ’90s. It was founded on the cusp of the internet’s mainstream adoption by artist Wolfgang Staehle, who considered it a living work of art all on its own (yes, there was a time when networked communication by itself felt like art).

The interface here, presented on a timeline showing who is participating and responding to whom and when, is pretty snappy—the relationships between everyone probably seem clearer than they were to the people involved. And it’s a total kick to be able to click through a time capsule of the momentary obsessions and debates of critics and artists circa 1993.

The BBS format probably seems as dated as Morse Code to today’s digital natives, but I think there’s also a kind of comfort in recognizing that both the highs and lows of discourse in threads like “Art Sucks! Beauty’s Cool ; – )” and “‘Political’ Art” are absolutely familiar from social-media jousting today.