Opinion

The Agony and the Ecstasy: Why Two ’60s Art Biopics Are Epic Clunkers, and One Is an All-Time Classic

Hollywood puts its stamp on the tales of Michelangelo and El Greco, but a medieval Russian icon-maker is the greatest star of all.

Hollywood puts its stamp on the tales of Michelangelo and El Greco, but a medieval Russian icon-maker is the greatest star of all.

Ben Davis

For Hollywood, the 1960s were a troubled time, deep into the waning of the Studio System and before the arrival of the more auteur-driven Hollywood New Wave at decade’s end. The spread of television had caused movie audiences to crater, which in turn caused major studios to invest in epic big-screen spectacle to lure audiences away from their Barcaloungers. Meanwhile, a flowering of non-Hollywood film made the foreign “art film” an attraction during the period, at least for the brainy set.

Both phenomena had their manifestation in the artist biopic genre. The Agony and the Ecstasy and El Greco mined the European art canon for costumed spectacle, but both in different ways ended up hilariously sinking under the weight of Hollywood formula.

It makes sense that the great work of the period came from a totally alternate film universe: the Soviet Union, where Andrei Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev dreamed up one of the strangest and most inventive of all “artist films” (though the Soviet system had its own problems, with Tarkovsky navigating official censorship; his opus was not known internationally until it went to the Cannes Film Festival in 1969).

This is the second part of a series on the history of artist biopics. The first part is here.

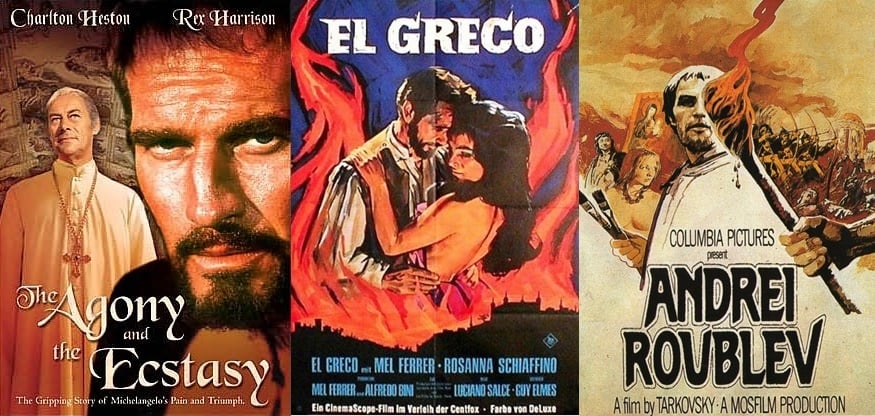

Poster for The Agony and the Ecstasy.

The Plot: Carol Reed’s brawny Michelangelo biopic is a film so epically self-important that it begins with an 11-minute mini-documentary explaining the greatness of Michelangelo via a narrated tour of his most famous works (pretty much the polar opposite of the screenwriting advice, “Show, don’t tell.”)

Charlton Heston makes for a rugged and earnest Michelangelo, and his chest is always showing. There’s not really an antagonist, unless you count the architect Bramante (Harry Andrews), his rival for the affections of warrior Pope Julius II (Rex Harrison). Bramante’s big scheme is… to reassign Michelangelo from making sculptures for the Pope to instead paint the Sistine Chapel.

Will Michelangelo be able to do it—even though, as he declares with manly angst, he’s a sculptor, not a painter? Such is the conflict of this film.

Unsurprisingly, this very mainstream ‘60s film gives no hint of Michelangelo’s passionate relationships with men (most prominently Tommaso de’ Cavalieri). Instead, it imagines a longing but unconsummated affair with Medici daughter Contessina (Diane Cilento), who helps nurture his manly genius and save him from his self-destructive urges.

But Michelangelo’s main romance, really, is with his own genius. Rebuffing Contessina’s sexual advances, he gives a comically sincere speech about how his art is his only love.

At the mid-point, The Agony and the Ecstasy serves up what is has to be the most over-the-top Artist Epiphany scene of all time. Having suffered a lack of inspiration and not wanting to be forced back to Rome to paint, Heston’s Michelangelo flees the Pope’s troops into the mountains above Carrera.

There, alone, he sleeps in a cave, wakes, and walks out onto a cliff to see the sunrise—which reveals an immense cloud formation that exactly resembles God reaching out to Adam! Michelangelo stares in awe, agape like a hooked fish. “And God… created man in his own image,” Heston’s voiceover intones. The music swells. Cut to Intermission.

What It Contributes: The Agony and the Ecstasy is wildly and wonderfully hokey. For all Heston’s anguished mugging, it is the rare artist biopic that is very firmly not a tale of tragic downfall. The guy loves making art; it’s the only thing he loves; eventually he makes it.

In fact, Reed’s film (knowingly?) inverts the typical artist film: Instead of an Artist’s Deathbed scene of Michelangelo expiring tragically, the film climaxes with the indomitable Michelangelo visiting the sick and dying Pope—who is so inspired by his spirited intellectual rivalry with the genius artist that he rouses himself from death’s door to reconquer the Papal States from the invading French!

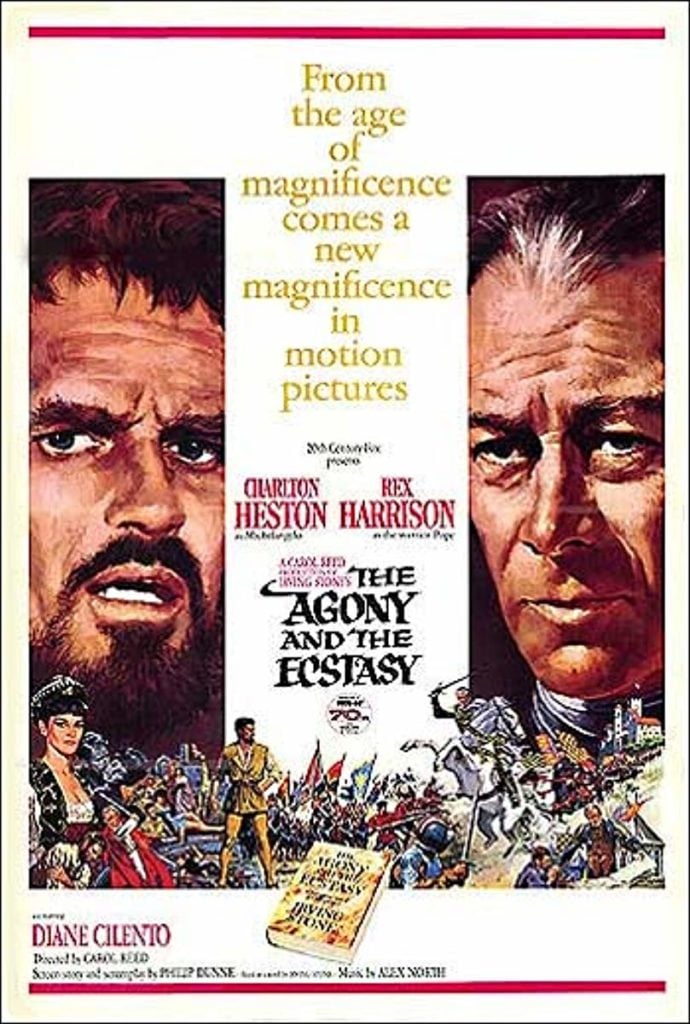

Poster for El Greco (1966).

The Plot: The 1966 El Greco is notable for being shot on location in Toledo and for its Ennio Morricone score. Other than that….

A film about El Greco (aka Doménikos Theotokópoulos) lives or dies by its El Greco, whose paintings are so strange and unique. Mel Ferrer (best known these days as Audrey Hepburn’s first husband) plays him with a leaden matinee-idol style more suitable for a biopic of Francisco Pacheco, if ya know what I mean (art history joke).

The film starts from El Greco’s arrival in Toledo, and mainly focuses on his affair with the comely Jeronima de las Cuevas, depicted as a noblewoman whose high-born status and betrothal to another prevent her from marrying a mere painter. (Little is known of the historical Jeronima, except that the two never married, probably because El Greco already had a wife back in Greece.)

The story has El Greco accused of trumped-up witchcraft charges by a rival, causing the artist to run afoul of the Inquisition. The fallout breaks the devoted Jeronima’s spirit while she waits for El Greco to clear his name; her death drives him to create his “greatest works,” a narrator explains—but he is a broken man.

It’s a more picturesque tale than the story of El Greco’s real-life decline: He was an in-demand working painter who lived in high style in Toledo—but was plunged into financial crisis after a dispute over payment for a work, and died in relative poverty.

What It Contributes: The dramatic high point of the film, El Greco’s showdown in court with the Inquisition, makes a modest contribution to what I’d call the Righteous Art History Lesson scene.

The Grand Inquisitor wheels out the Disrobing of Christ (1577–1579) as evidence of his blasphemous tendencies, accusing El Greco of heretical improprieties. El Greco defends his own piety with unshakably square-jawed conviction, schooling his critic with a lengthy, impassioned monologue about how he balances the demands of religious symbolism and realistic perspective.

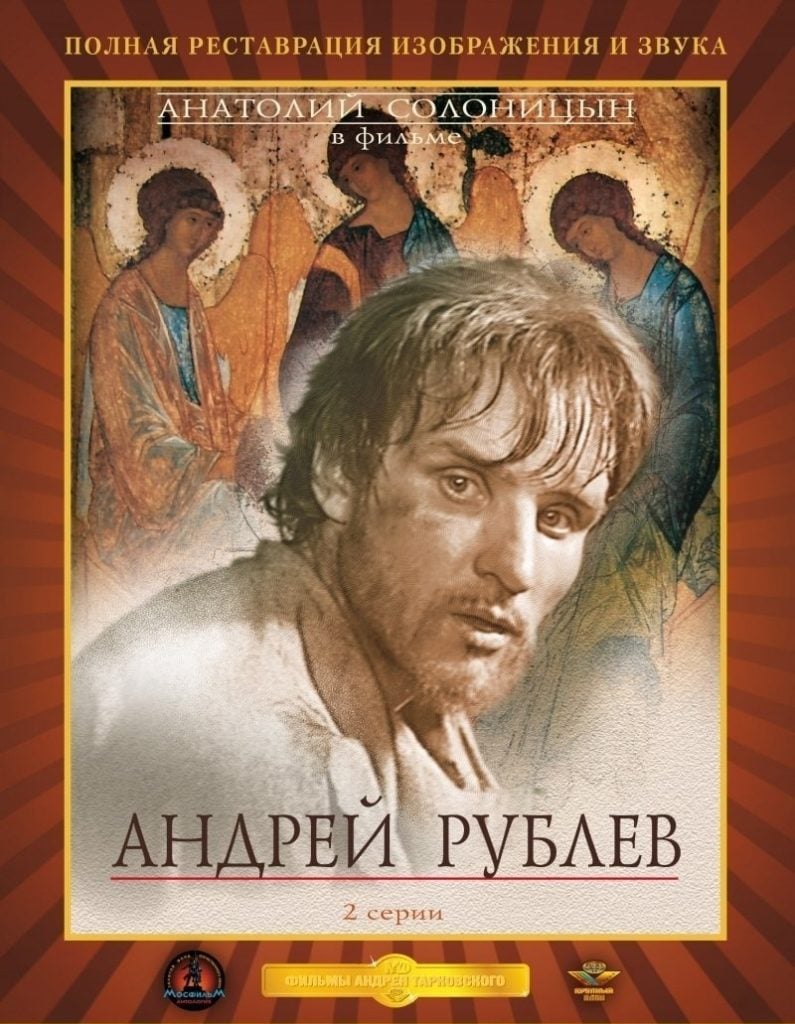

Cover for Russian version of Andrei Rublev (1966).

The Plot: The fact that the lumbering El Greco was released the same year as Andrei Tarkovsky’s visionary, completely unique Andrei Rublev is mind blowing. It is one of the most absorbing of all artist films, which is all the more amazing in that it cannot depend on familiar modern tropes, Rublev being a medieval icon-painter and Russian Orthodox saint.

Andrei Rublev is unsummarizable. Told in chapters, it begins with a prologue of a man attempting to escape a mob via a crude hot air balloon; soaring away from the frenzy of battle, he gets a brief view of the rugged landscape from on high before crashing uncontrollably to earth. That’s a metaphor for the feeling of the film overall, of characters being hitched to vast forces of history that they only half control, buffeted by circumstance, stealing glimpses of epiphany, hurtling towards disaster.

We gradually explore the world of the pious Rublev (Anatoliy Solonitsyn), and in successive chapters see him find a mentor and assistants—and then have his faith terribly tested as he is swept up into, in succession, an ecstatic pagan rite and then a harrowingly vivid military siege.

The film’s justifiably most celebrated episode is almost a movie within a movie, not even about Andrei Rublev, but concerning the herculean efforts of a young man (Nikolai Burlyayev) to command the massive project of forging a huge church bell. You will have to take my word for it that the beat-by-beat depiction of the bell’s creation builds to something really heart-stopping.

What It Contributes: For most of the film, you see Rublev struggle with his vocation and refuse to paint, in particular balking at a commission for a Last Judgment because he refuses to sow fear among the people. In his famous final flourish, Tarkovsky’s sober black-and-white yields suddenly to color close-ups of the icons the artist is remembered for, a device that gives them the feeling of otherworldly revelation.

A commonplace of commentary on the film is that, after following the artist’s struggles in the preceding nearly three hours, you feel freshly connected to the icons—that the biography “explains” the art. I’m not so sure it’s that linear: Rublev’s icons are, on the whole, serene and otherworldly compared to the barbarity and heartbreak of the depicted world of Andrei Rublev. The contrast feels part of the point.

And after all, no matter how generative and individual Rublev’s style was, it wouldn’t have been recognized as an expression of “his” life during the historical period it was made—that was not how art functioned back then. One of the accomplishments of Tarkovsky’s film is to give a subtly more medieval sense of the artist’s vocation, putting the viewer outside of familiar expectations.

There’s a reason why the longest episode of Andrei Rublev isn’t even about Andrei Rublev but about a totally other kind of struggle for creation, the bell-forging. The point is clearly that the struggles art channels here are more collective than merely personal, that history flows through art in ways more mysterious than the ordinary biopic formula where each famous work is explained by some moment in an individual artist’s life.

That vision opens up a whole world of new possibilities for telling stories about artists and art—though not too many filmmakers have had the imagination to take them up.