Every Monday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, discussing a different kind of art-market guarantee…

BASIC INSTINCT

On Thursday, a coalition of more than 300 Canadian artists, arts workers, and institutions publicly released a letter addressed to prime minister Justin Trudeau and other high-ranking officials urging the creation of a permanent basic-income guarantee nationwide. And while the letter from our friends in the North technically only addresses the plight of their own population, its timing and its cogent framing of the larger issues also show why artists and arts workers everywhere should care.

Authored by artists Craig Berggold, Zainub Verjee, and Clayton Windatt, the letter continues a recent surge of momentum at the highest levels of Canadian politics for universal basic income—in its most utopian form, an unconditional regular payment that would be made to citizens, regardless of their employment status, to guarantee a minimum standard of living.

CanadianArt notes that the Parliamentary Budget Office released a report on national universal basic income (UBI) on July 7, largely in response to British Columbia senator Yuen Pau Woo’s advocacy for the relief it could provide Canadians buffeted by the grand shutdown of 2020. More than 1,200 residents, including many artists, also backed a pro-UBI petition sent to the Canadian House of Commons last month.

Although artists have been a major power source for UBI’s propulsion into the Canadian consciousness, the brilliance of the new letter lies in its erasure of the boundaries separating art-world problems from wider-world problems. Its authors argue that UBI is needed to counteract the rise of a two-headed serpent: the worsening insufficiency of social-welfare programs at all levels of government, and the growing dominance of gig work such as driving for ride-share startups and food-delivery services. Here’s the key passage for my money:

The gig economy is undermining decades of worker protections. As participants, many arts-and-culture-sector workers are subject to precarious short-term contracts, without access to benefits, paid sick leave, or even employment insurance. Today, the world of general labor is looking a lot like the way art labor has looked for decades.

In other words, these problems have been slowly metastasizing over many years, but the lockdown and its effects on the economy have accelerated them to a dire new degree. Establishing UBI, the letter’s signatories say, is exactly the kind of radical response necessary to solve such an insidious problem.

Yet Canada and its art industry are far from the only places on the globe under this same malicious strain. And this reality became clear by way of multiple distressing announcements from elsewhere in the art world this week.

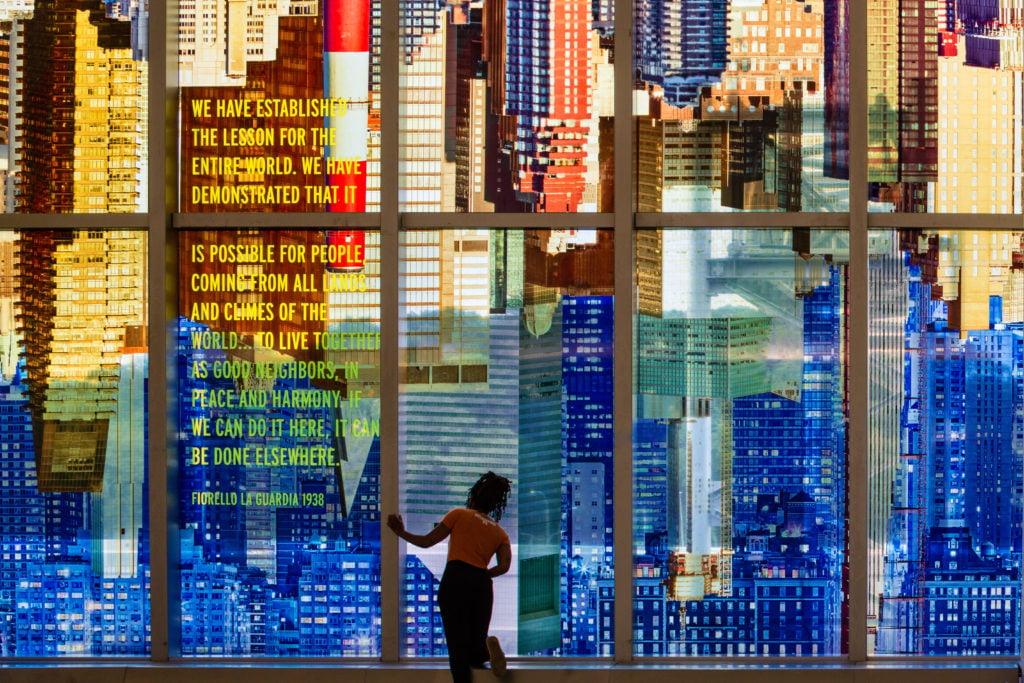

Sabine Hornig, La Guardia Vistas (2020). Photo by Nicholas Knight, courtesy of the artist; LaGuardia Gateway Partners; Public Art Fund, NY; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles. ©Sabine Hornig and VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn Germany.

GLOBETROTTING

Let’s start with the cold winds blowing out of arts institutions in New York City. On Thursday, my colleague Taylor Dafoe laid out the findings of a new report by Southern Methodist University’s DataArts initiative: after combining lost revenue and shutdown-related expenses, New York cultural institutions have hemorrhaged a knee-buckling $500 million since March. Their laborers took arguably the most direct hit, as the shutdown vaporized over 15,000 jobs totaling about 21 percent of the overall cultural workforce.

The survey compiled responses from 810 of the almost 1,300 nonprofits given funding by the city’s department of cultural affairs. Not surprisingly, the results showed the financial damage was disproportionately weighted toward smaller organizations; major museums suffered the least. Daniel Fonner, who spearheaded the study, summed it all up by saying, “What was difficult about this project, in a way, is that a lot of it is just bad news.”

British cultural institutions can relate. Also on Thursday, after being prodded by a skeptical, data-backed inquiry from the Art Newspaper, the Creative Industries Federation—an organization with members from across the spectrum of UK arts professions—dramatically revised its mid-June estimate of the losses likely to be faced by the museums, public galleries, and libraries in its constituency. Instead of a nine percent, roughly £743 million ($934 million) decline, the federation is now anticipating a demon drop of 45 percent, or more than £3.7 billion ($4.7 billion) in losses. Cue an organ blast from a vintage horror movie.

A Creative Industries Federation spokesperson called the original projection “an honest mistake at a time when many of our partners were incredibly stretched and thinly resourced.” Which, if true, kind of just drives home the point here, doesn’t it? When the arts sector doesn’t have enough money, time, or staff to do its work properly, the end product will probably suck. It’s just as true in London or New York as it is in Toronto or Vancouver. This would make a universal basic income… well, universally valuable to arts workers around the world.

But the benefits are about more than just boosting the quality of cultural production, of course. It’s also just a simple matter of quality of life. No other news clarified this concept as forcefully as still another report—this one from outside the art world, published two days before the Canadian UBI letter and the two art-industry studies I mentioned above.

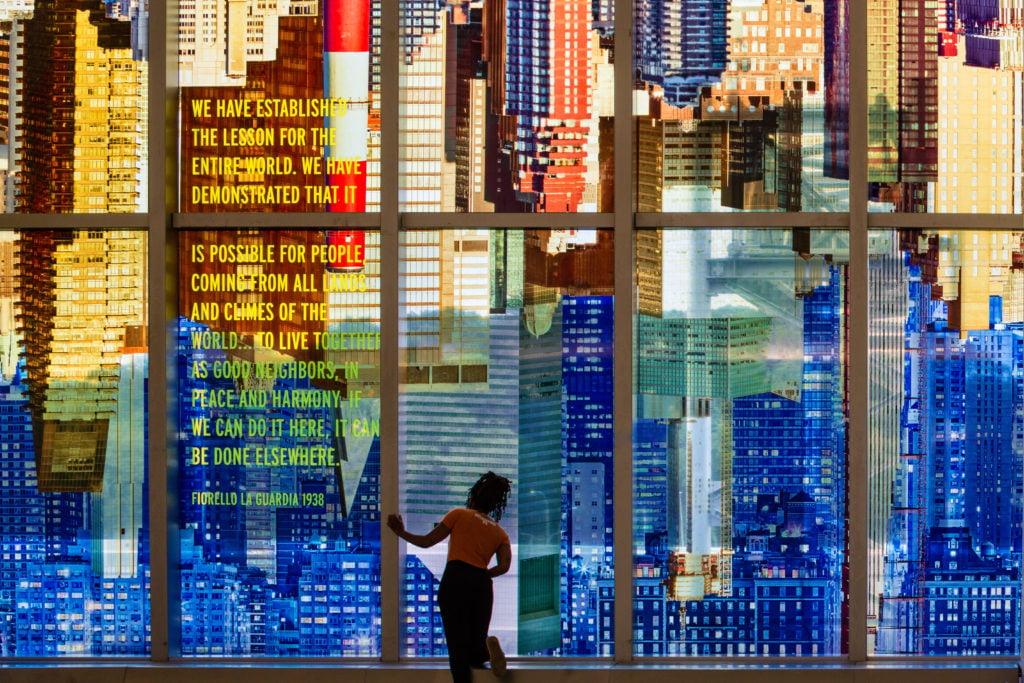

Visitors look at Do Ho Suh’s site-specific work Home Within Home at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea in Seoul. Photo Jung Yeon-Je/AFP/Getty Images.

HOUSES IN MOTION

On Tuesday, the National Low Income Housing Coalition released its annual “Out of Reach” report, which crunches numbers on the affordability of home rentals for the lowest-earning laborers in all 50 American states. The results are so grim that they might as well have been handed over by a skeleton in a hooded black robe.

As CNBC broke down, the study found that a full-time employee earning the local minimum wage nets too little to responsibly afford a one-bedroom apartment in 95 percent of counties across the US… and, for the second consecutive year, too little to afford a two-bedroom anywhere in the nation.

The findings are based on allotting no more than 30 percent of annual income for housing—the maximum advised by a wide swathe of budgeting experts, including US government officials, since the 1980s. (Except in certain special situations, minimum wage in the US currently ranges from $7.25 to $14 an hour, depending on the state.)

How many hours would a single minimum-wage laborer need to work on average to budget for these two types of homes? The answers are roughly 79 hours a week for a one-bedroom, and 97 hours a week for a two-bedroom. Which means this slice of the labor market—one that, perversely, happens to include millions of workers labeled “essential” during the shutdown, such as grocery-store staffers, delivery drivers, and food-service employees—could only manage to do so by either working a second full-time job, and/or taking on exactly the kind of gig work the 300-plus signatories of the Canadian letter identified as a central reason UBI is needed.

Yet many artists and arts workers aren’t much better off than minimum-wage earners, if they are better off at all. Yes, the growing ranks of laborers unionizing (and attempting to unionize) at US cultural institutions are, in a very real sense, rallying around deeper structural issues. But the fight for fair wages has pounded out a consistent drum track to their efforts, especially in arts hubs where, as more-on-point-than-he-was-given-credit-for New York gubernatorial candidate Jimmy McMillan noted, the rent is simply too damn high.

(Fun fact: When I see Andrew Cuomo, who has slurped up more money from New York’s real-estate lobbyists than any other donor, laughing like a suited gargoyle after McMillan says his peace in that clip, my entire body momentarily ignites like the Human Torch.)

As much as I hate to say it, the situation is poised to get even worse for the rank-and-file American art world. Here’s a bit of marrow-chilling context from the CNBC summary of “Out of Reach”:

With all of that as the backdrop, housing experts forecast a coming housing “apocalypse” at the end of July: Eviction bans put in place at the start of the pandemic are lifting, just as enhanced unemployment benefits expire. That could lead millions of households to face eviction and potentially homelessness as they choose between covering rent and basics like food and medicine.

All of which illustrates the point made by the 300-plus signatories of the pro-UBI letter to Canadian officials: the world of general labor is looking a lot like the way art labor has looked for decades. From Canada to New York to the UK and beyond, too many of us are all facing the same structural peril for the same structural reasons. Arts workers’ rights are human rights, just channeled through one particular prism.

I’m not sure if universal basic income is the only, or the best, skeleton key to get the art industry out of this dungeon, but I am sure about this: the sooner artists and arts workers in one location can connect their local concerns to their counterparts elsewhere, as well as to those of the broader labor force suffering under the same injustices, the more achievable genuine transformation should be. Canada’s art world sees it. Hopefully others will, too—and soon.

[Ontario Basic Income Network | CanadianArt]

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: fairness is simultaneously the simplest ask… and the most complicated one of all.