Every Monday morning, artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, another window into how the financial can be political…

HOUSE STYLE

On Friday night, artist Eric Doeringer opened a new show called “Christy’s,” in which he presents his own “bootleg” versions of some of the premier works due to be sold in Christie’s postwar and contemporary evening sale on May 15. Put on in collaboration with A Hug from the Art World, Adam Cohen’s combination online-store and nomadic gallery, the exhibition raises all kinds of interesting questions about value—and values—in the world today.

The marquee lots include Robert Rauschenberg’s Buffalo II, Jeff Koons’s Rabbit, and Andy Warhol’s Double Elvis (Ferus Type), each estimated in the range of $50 million to $70 million. Doeringer’s works, by contrast, are priced at $1,000 each, sometimes with multiple editions available for multiple customers. Granted, they are also only a small fraction of the size of their respective inspirations—for example, Robert Rauschenberg, Doeringer’s riff on Buffalo II, measures 12 by nine inches versus the original’s eight by six feet—but you have to sacrifice something obvious for such a massive discount, right?

The press release for Doeringer’s show rightly emphasizes the distinction between bootlegs, which are homages openly acknowledged as such, and “fakes” or “forgeries,” which are meant to deceive people into believing they are the genuine article. It’s the difference between an original but unlicensed band T-shirt you can buy in a concert venue’s parking lot and the impostor Coach bags you can buy on Canal Street. (Notably, New York Times pop music critic and merch connoisseur Jon Caramanica once labeled bootleg tees a form of American folk art.) Ultimately, transparency matters.

Jeff Koons, Rabbit (1986). Courtesy of Christie’s.

“Christy’s” is only the latest in Doeringer’s nearly 20-year practice of riffing on blue-chip art and well-known industry functions. His first project, launched in 2001 and simply titled “Bootlegs,” consisted of painting small replicas of in-demand artists’ works and selling them on the sidewalk in Chelsea or outside major art fairs. Since then, he’s also created entire bootleg cycles of famous On Kawara series, glosses on famous artist books like Ed Ruscha’s Some Los Angeles Apartments, and even an eBay-only version of Rob Pruitt’s Flea Market.

Of course, Doeringer isn’t the first artist to raise questions about the art market, which places more of a premium on authenticity and exclusivity than on imagery and meaning. Artists have been making works that tacitly interrogate collectors’ and institutions’ (arguably flawed) priorities for decades. Sturtevant and Richard Pettibone both spring to mind as approved-by-the-art-world postwar talents who made careers out of transparently reproducing canonical works, often by hand rather than through mechanical reproduction or industrial fabrication.

But not all bootlegs are created equal, in terms of either their commercial value or their conceptual impact. And one lesser-known example clarifies as much in terms especially relevant to today.

Installation view of “William Kentridge: Journey to the Moon” at the Underground Museum in 2015. Photo by Brian Forrest. Courtesy of the Underground Museum.

NOTES FROM THE UNDERGROUND

In 2013, the artist Noah Davis opened an exhibition called “Imitation of Wealth” at the Underground Museum, the nonprofit space he had co-founded with his wife, the artist Karon Davis, in Los Angeles’s Arlington Heights neighborhood the year before. Davis created and exhibited a grouping of artworks visually indistinguishable from the blue-chip pieces from which they were adapted, including a Dan Flavin fluorescent-light sculpture, an On Kawara date painting, and a Jeff Koons vacuum-cleaner vitrine (for which Davis sourced an identical Hoover model from Craigslist).

At first glance, “Imitation of Wealth” looks like a natural midpoint between, on one side, the likes of Sturtevant and, on the other, Doeringer’s latest show. But what sets “Imitation of Wealth” apart in my mind is its context—and the deeper socioeconomic issues embedded within that context.

The Davises specifically started the Underground Museum because there was no “museum-quality art,” as Noah put it, “in walking distance” of the predominantly working-class, predominantly African American and Latinx community of Arlington Heights. And “Imitation of Wealth” became perhaps the most pointed possible response to this situation.

Davis chose to recreate the canonical masterpieces in the show because he could not convince any museum to loan the real thing to his startup institution. (These limitations faded in 2015, when the Underground Museum established an official partnership with LA’s nearby Museum of Contemporary Art—sadly, the same year Davis died from a rare form of cancer at age 32.) In this sense, the exhibition raised all of the same questions about aesthetics and financial worth as art bootleggers past and future, while also raising more fundamental questions about power, equity, and exclusion.

Foremost among them: Who controls the distribution of resources deemed valuable in our society, and on what basis?

The answers radiate far beyond the art world. They touch everything that people of color, the LGBTQ+ community, and the working class deal with on a daily basis. “Imitation of Wealth” just managed to visualize that struggle in a particularly niche way thanks to its venue, its origin, and its nonprofit status. In the process, it reframed the entire discussion surrounding bootleg or appropriation art.

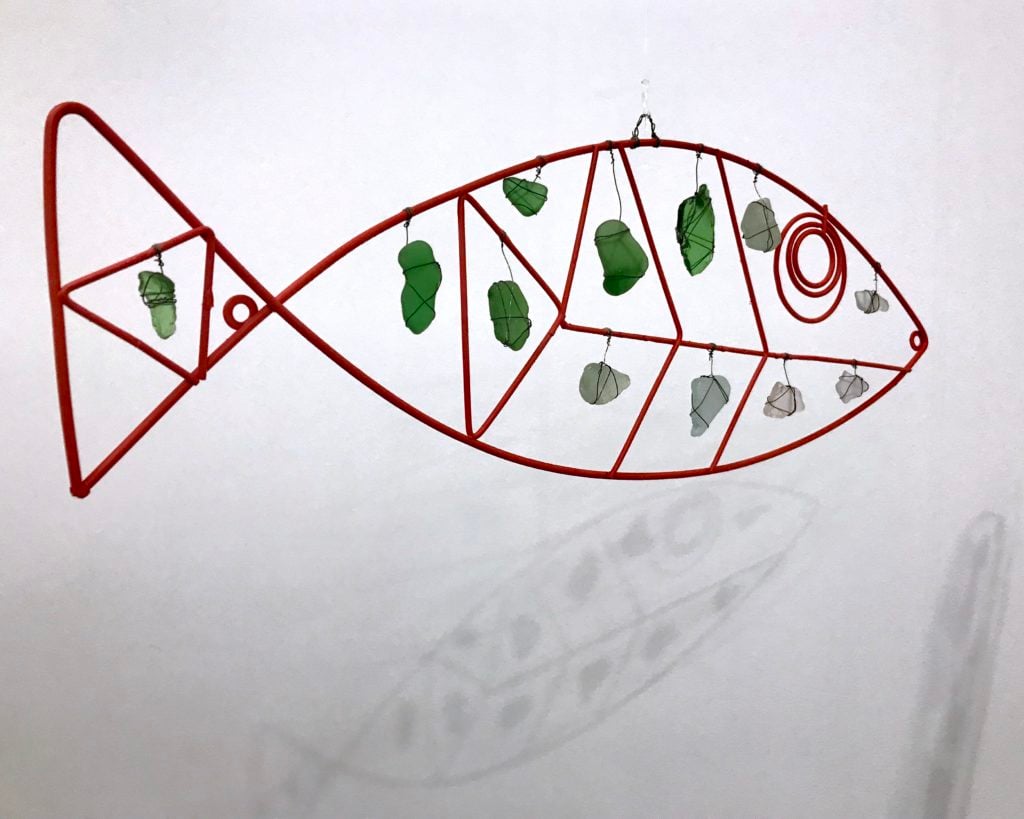

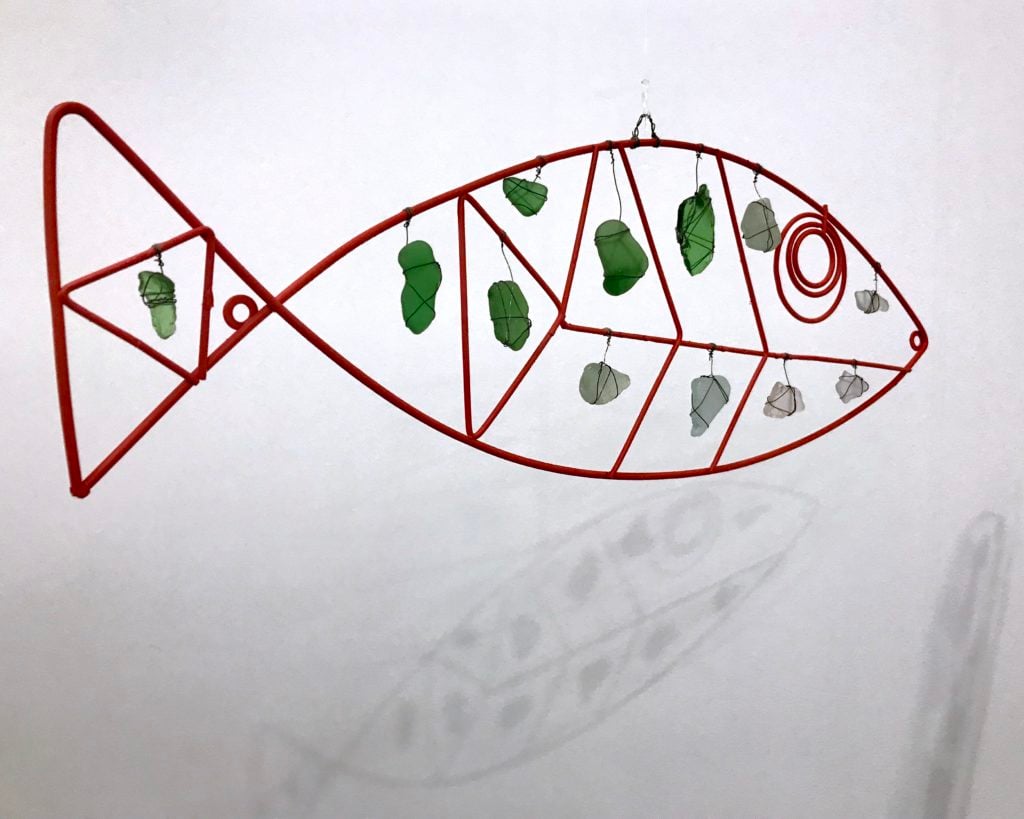

Eric Doeringer, Alexander Calder, 2019. Photo by Tim Schneider.

INSIDE THE FRAMEWORK

Geographically and conceptually, “Christy’s” does not deviate as far from the mainstream art world as “Imitation of Wealth” did (although the divide is a little narrower if you consider that MOCA restaged Davis’s show in its own storefront space in 2015). While I think some of that may be unavoidable—Doeringer is a white man, which, like it or not, some would see as automatically freighting the presentation with privilege regardless of all other circumstances—a big part of the reason has to do with the business decisions surrounding the show.

Doeringer’s exhibition takes place inside a pristine, white-walled space in Chelsea’s freshly opened High Line Nine gallery complex, where blue-chip gallerist Paul Kasmin recently expanded. This is about as down-the-middle as you can get in the elite New York art world. And sure, the bootleg works on offer cost a small fraction of their megawatt inspirations’ eventual hammer prices. But they still comprise a typical selling show with asking prices above what an average member of the working class could likely afford, as evidenced by a 2018 study that found 40 percent of Americans would be unable to pay a $400 emergency expense. All in all, then, “Christy’s” is rebellious in only a lower-case “r” kind of way.

None of this is meant as a slam of Doeringer or A Hug from the Art World. Broadly speaking, I like what they’re after—the art world needs more merry instigators as badly as a Texas barbecue joint needs a bulk-supply of moist towelettes—and I thought the execution of the “Christy’s” works was generally pretty impressive. But based on the market structures and expectations being adhered to, there are limits to the kinds of arguments they can make about value systems in 2019.

Ultimately, this is why “Christy’s” simultaneously means more and less than it aims to: the show clarifies that, to some degree, it is impossible to separate the business decisions about art from the meaning and social impact of art. And that’s the case whether the works are sold for millions of dollars, thousands, or not at all.

[Press release]

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: If you look hard enough, it’s rarely ever “just business.”