Every Monday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, abandoning sales comps for criminality comps…

ONE WAY OFF THE ISLAND

On Friday afternoon, a new chapter opened in the most breathlessly followed art-world scandal of the past year as American federal agents arrested fugitive dealer Inigo Philbrick on the Pacific island of Vanuatu. Authorities subsequently transported Philbrick to Guam, where he will appear in court immediately to face charges stemming from what the US Department of Justice termed “a multi-year scheme to defraud various individuals and entities in order to finance his art business.” And although this remains a developing story, I think it’s instructive to analyze where Philbrick fits into the art-crime history books today.

My colleague Eileen Kinsella (who has been reporting the hell out of this story, in text and in audio, since it broke in fall 2019) relayed that the DOJ’s case against Philbrick currently involves more than $20 million in allegedly fraudulent transactions. Calling that a modest amount of criminality would be as much of an understatement as saying I thought it was “mildly amusing” that Philbrick was ultimately found hiding out on the island from season nine of the reality-TV eco-endurance challenge Survivor. (I can only hope host Jeff Probst will appear after the verdict in the eventual trial to solemnly announce, “Inigo, the tribe has spoken.”)

And yet, the accusations against Philbrick could be worse—a lot worse, it turns out!

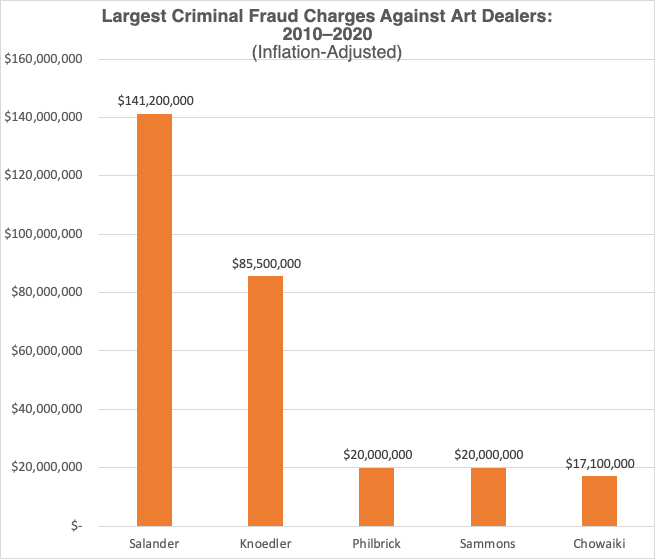

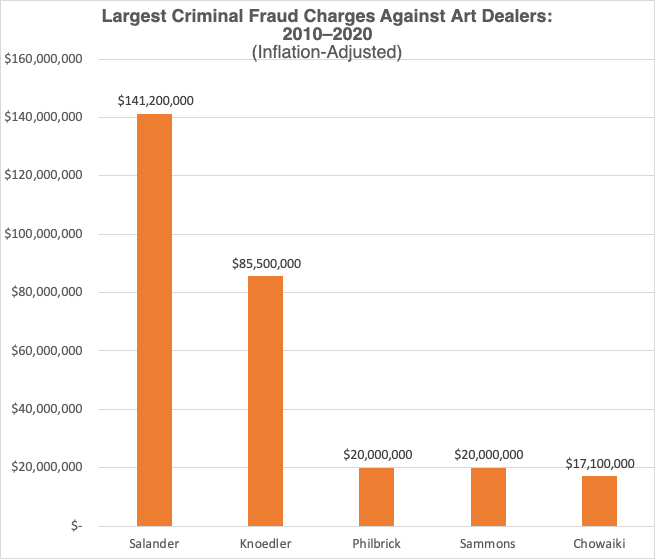

Below is a chart I threw together that stacks up the dollar value of Philbrick’s alleged fraud, according to current federal charges, against the amounts accumulated by other recent art-market rogues. To keep the parallels as bad-apples-to-bad-apples as possible, the figures here strictly come from the criminal charges against the dealers in question; trying to incorporate all the different civil actions against them spins the comparison out of control.

Chart by Tim Schneider. © 2020 Artnet News.

At publication time, then, the Philbrick scandal was only about one-seventh as severe as the one traced back to disgraced dealer Larry Salander in 2010, and less than one-quarter as heinous as the infamous Knoedler forgery saga in 2016. (The total alleged frauds at the time reached about $120 million and $80 million, respectively, in the two cases, but my pathological lack of chill meant that I had to adjust everything for inflation.)

As the chart shows, the two closest comps I could find for Philbrick were British charlatan Timothy Sammons and New York con man Ezra Chowaiki. In 2019, Sammons was charged with bleeding clients of somewhere “between $10 million and $30 million” in sales and financing deals for works by various canonical Modernists. (Since the charges were never pegged to a definitive figure, I chose the midpoint of the range.) Prosecutors charged Chowaiki with defrauding buyers and business partners of more than $16 million between 2015 and 2017—just over $17 million after inflation—primarily by selling stakes in works he didn’t own and pocketing collectors’ cash for works he never actually bought on their behalf.

To me, this comparison foregrounds two points. First, it’s notable that Philbrick is currently only sharing the bronze medal for art-dealing knavery in the 2010s. This makes criminality look like just one more area where the art market’s totals have stagnated in the past 10 years.

Second, the Sammons and Chowaiki trials should help set expectations for what kind of punishment Philbrick might be facing if convicted on all current counts. Sammons earned four to 12 years in prison for his crimes; Chowaiki was hit with an 18-month prison sentence, a bill for $12.9 million in damages, and a forfeiture order for 25 artworks he once partly or wholly owned. At 33, Philbrick is still young enough that even a high estimate for any possible jail sentence would leave him with plenty of time to try to launch a second act after release.

But both of those points still hinge on one variable that is still very much a free radical.

Inigo Philbrick scammed high-flying art collectors around the world. Photo collage: Artnet Intelligence Report.

THE NEXT EPISODE?

For anyone who hasn’t been bingeing on legal procedurals since the shutdown, I should emphasize that the initial charges that land a defendant in court will not necessarily be the only charges on the docket by the time their trial actually starts.

In general, a good prosecutor will refuse to order an arrest until they’re all but sure they can convict the alleged culprit on their initial charges. After a defendant is in custody, though, they will try to expand and strengthen the case with additional evidence that can lead to additional counts of criminality. One popular strategy for doing this: questioning and charging the defendant’s potential accomplices with related crimes to try to compel them to flip on the kingpin.

This is why the nature of Philbrick’s alleged fraud, not just its current dollar value, is important to consider. What separates the accusations against him from those against earlier art-market fraudsters is the purported complexity of the deals. According to previously reported allegations, this wasn’t just a case of one man selling artworks he didn’t own to individual clients (as Salander did), or even collaborating with a small, tight circle of accomplices to peddle forged works (as dealer Glafira Rosales did in the Knoedler case).

Exterior image of Reading Prison. Photo: Morely von Sternberg, courtesy Artangel.

Instead, Philbrick regularly relied on complex art-financing deals and sales partnerships with various offshore entities and shell corporations, most of whose founders tended to be looking to flip blue-chip art for a big profit. (Eileen Kinsella wrote the most thorough accounting of the machinations you’ll find.)

The more layered and more profitable the con, the higher the likelihood that someone else involved at least knew what the perpetrator was really doing, if not materially aided them. It also stands to reason that the central perpetrator in one con might have evidence of other wrongdoing that they would be happy to divulge to authorities in hope of improving their own situation if caught.

By no means am I suggesting that all, or even most, of the people who did business with Philbrick were criminals. Every con has legitimate victims. My colleague Kenny Schachter, for instance, has publicly unspooled (on both Artnet News and elsewhere) his tale of how Philbrick leveraged their years-long friendship into a scheme that he claims robbed him of “well over $1 million.” I’m just saying that I doubt I’m the only one who wondered whether part of the reason Philbrick managed to evade the law for so long was that some of his former associates preferred he quietly disappear rather than land in an interrogation room.

For those reasons, I think it’s still too early to say we understand the full scope of the Philbrick case. “More than $20 million” in fraud may be only a solid starting point for prosecutors, and the list of defendants for related charges could still expand.

His inclusion in the pantheon of crooked art dealers is already secure. All that’s left is to determine his proper placement in the hierarchy.

[Artnet News]

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: everything ends eventually.