Every Monday morning, artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, asking if art stars could learn from a pop star…

BAD BLOOD

On Monday, after polarizing pop supernova Taylor Swift took to Twitter to tell her fans she might be unable to perform a career-spanning set at the upcoming American Museum Awards due to a dispute with her former record label, the Hollywood Reporter relayed that Big Machine Label Group would grant all necessary licenses for the performance after all. But the broader rift between Swift and her former label—which has resulted in both death threats and comments from presidential candidates—could open up a radical option for contemporary artists who want to capitalize on their own resale markets.

For the uninitiated, this volcano erupted after Scooter Braun, the powerful music manager whose clients include Justin Bieber and Ariana Grande, acquired Big Machine Label Group earlier this year for a reported $300 million. The deal gave Braun’s Ithaca Holdings control of the group’s full slate of current contracts and past releases, including the master recordings (or just “masters,” in industry speak) of Swift’s first six multiplatinum albums, which she made with Big Machine Records through a contract she signed as a teenager. (Big Machine is the namesake, but not only, label in the group.)

Aside from Swift’s longstanding antipathy for Braun and, more recently, Big Machine Label Group president Scott Borchetta, it was the acquisition of Swift’s masters that ignited what the New York Times’s (essential) Popcast dubbed “the pop music civil war of 2019.” (Click through for more background; like eating a fresh mango with only your bare hands, it’s juicy, but complicated.) And it is Swift’s unorthodox attempt to regain control of her old work that chefs up food for thought for star-level painters, sculptors, and other artists working in traditional media.

![Andy Warhol, Double Elvis [Ferus Type] (1963). Courtesy of Christie's Images Ltd.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2019/05/double-elvis-new2-660x1024.jpg)

Andy Warhol, Double Elvis [Ferus Type] (1963). Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

I KNEW YOU WERE TROUBLE

Now, the business of music is arguably just as arcane and potentially exploitative as the business of fine art, if not more so. For efficiency’s sake, here are the absolute basics you need to know to understand Swift’s potential relevance to the art market.

A record makes money through royalties, which have to be paid anytime the record gets purchased (as a hard copy or MP3), played or performed in a public setting (including on the radio, in a sports arena, or at another artist’s concert), or used as a soundtrack for moving images (meaning in a movie, TV show, or commercial).

The key is that different royalties are worth different amounts, and they go to different parties based on who holds which form of copyright on a record. (Again, it’s complicated, but here’s a primer on music royalties for my fellow knowledge maniacs.)

The most valuable copyright, literally and figuratively, belongs to whoever owns the masters—the original, finalized recordings that all other copies are made from. (Obviously, the notion of “copies” gets a little squishy in the streaming era, but suffice it to say intellectual property attorneys have been paid obscene amounts of cash to figure out answers.)

When you own the masters of a record, you get the final say in how that record can be licensed out in the world, and you get the meatiest royalties from those licensing deals. And in a classic example of pro-management standard-setting, the masters normally belong to the person who financed the recording of the music, not the person who wrote or performed it—meaning, almost invariably, the record label.

Prince put this arrangement in the most bracing terms during a dispute with his then-label, Warner Bros., in the ‘90s: “If you don’t own your masters, your master owns you.” (He also memorably took to scrawling the word “slave” on his face before public appearances during this stretch.)

In essence, then, the recording industry has been designed to operate so that artists normally don’t receive the most lucrative part of the upside when their careers take off. Why? Because someone much richer owns the valuable physical manifestations of their talent, which can be resold to the highest bidder—sometimes for tens, even hundreds, of millions of dollars.

Is this starting to sound familiar? Would it help to think back to, I don’t know, the over $1.1 billion in New York auction sales at Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips earlier this month, all of which went to private sellers, dealers, and the houses thanks to America’s lack of an artist resale royalty right?

BETTER THAN REVENGE

It is from this wormhole linking the music industry and the art industry that, surreally, Taylor Swift emerges with a plan that may be useful to both.

In August, Swift confirmed in an interview with CBS that, starting in November 2020, she will exercise a clause in her contract that allows her to re-record the first five albums she made with Big Machine. (Reputation, the sixth and final record released through her old label, seems to be ineligible.)

Crucially, Swift herself will own the masters of the re-recorded albums, giving her the power to effectively replace nearly all of the songs now controlled by Braun and Big Machine—and to redirect the accompanying royalties into her own pocket.

Swift’s strategy begs a question: Could commercially successful artists claim a new measure of control over their market by remaking some of their valuable earlier works?

There is precedent for this conundrum in the art world. In 2014, artist Wade Guyton’s glitchy canvases, often made by disrupting the functions of large-format printers, were an auction-market sensation. The heat led Loic Gouzer, then rising through the ranks at Christie’s, to include Guyton’s Untitled (Fire, Red/Black U) (2005) in the first and most infamous of his themed sales, “If I Live I’ll See You Tuesday,” at an estimate of $2.5 million to $3.5 million.

Apparently not thrilled with his work going under the hammer, Guyton became something of an art-world folk hero by Instagramming a series of photos showing his studio continuously printing additional versions of the painting from the master file. He even trolled Christie’s in the captions with hashtags like #ifiliveauction, #deflationarypolicy, and #firestormtopurify.

The message seemed clear: auction the painting if you want, but I’ll devalue the crap out of it by retroactively reducing it from a unique work into a potentially unlimited edition.

However, to my knowledge, Guyton’s retaliation deviates from Swift’s in one crucial way: he didn’t monetize the new versions of Untitled. (I wrote to his New York gallery, Petzel, to try to confirm whether the canvases were destroyed, and a spokesperson replied that Guyton was unavailable to comment.) His mass-printing barrage could have only obliterated value for someone else, not recaptured it for himself.

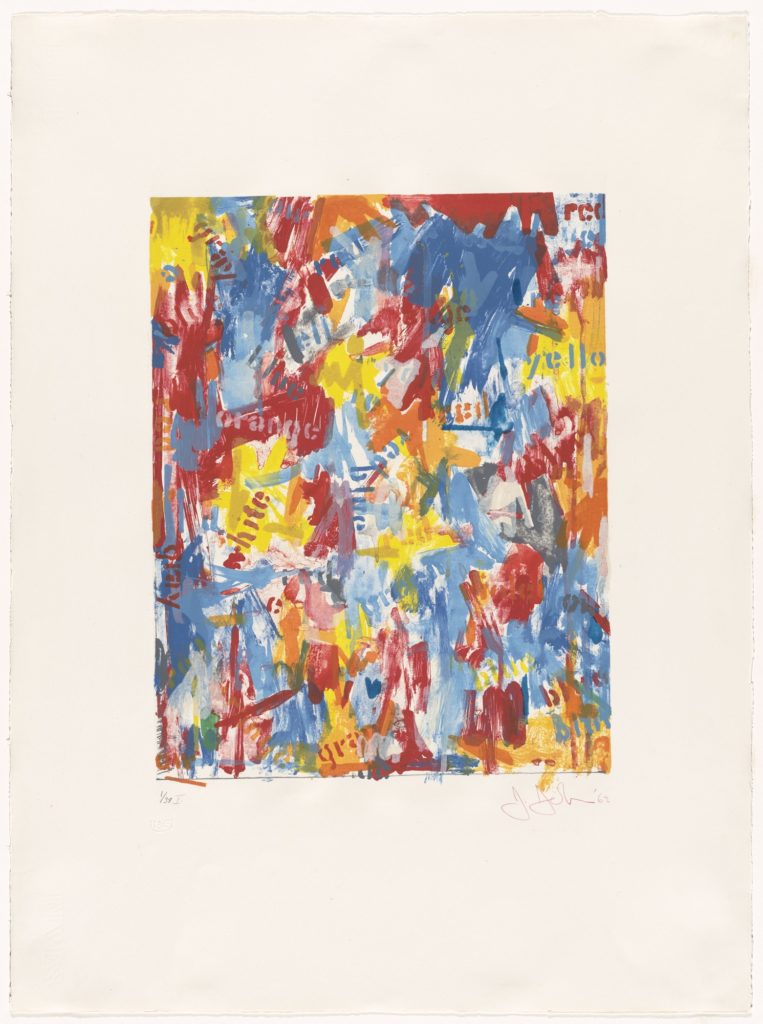

Yet another, closer parallel to Swift’s strategy re-emerged from the depths of art history last week: the one and only Jasper Johns, all the way back in 1964.

Jasper John’s False Start (1962). Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

YOU BELONG WITH ME

On Tuesday, ARTnews ran a deep dive after my own heart, in which Greg Allen unwound the fascinating behavioral-economic knot tying Johns’s first dealer, the legendary Leo Castelli, to two philosophically opposed collecting couples: old-money Burton and Emily Tremaine, and new-money Robert and Ethel Scull.

Allen’s launchpoint is a provocative paper in the Columbia Journal of Law & the Arts called “The Gallerist’s Gambit.” There, co-authors Michael Maizels and William Foster argue that Castelli supercharged his artists’ careers early on partly by engineering ethically dubious appraisals to deliver massive tax breaks to collectors, which in turn spurred them to donate certain acquisitions to the Museum of Modern Art. Allen uses additional research into the Castelli archives to plug that element into a larger story about the psychology and incentives that warp the high-end art market into the pretzel of madness that it is today.

One theme that emerges in Allen’s piece is that the Sculls were simultaneously crucial to Castelli and Johns’s transformation into art-historical juggernauts… and borderline-toxic to deal with at times. Case in point: As an aside, Allen mentions digging up information that “the temperamental Sculls threatened to withhold” certain important works they owned from Johns’s 1964 Jewish Museum survey “for so long, the artist remade some key paintings as potential replacements.”

Allen was gracious enough to pinpoint the specifics for me in an email exchange over the weekend. In an oral history in the Archives of American Art, Castelli intimated that Johns tried to backstop Scull’s possible refusal to lend the vibrantly colored meta-painting False Start (1959) by making Arrive Depart (1963–64). While the latter isn’t an identical replacement, it looks an awful lot like False Start with a toned-down palette and a skull (get it?) in one corner.

If there were other failsafes, neither Allen nor I know what happened to them. My email inquiry about this episode went unanswered by Johns’s dealer Matthew Marks, and I didn’t have time to rampage through the artist’s catalogue raisonné of paintings to see if it harbored any answers. The Sculls ended up agreeing to the loan requests at the eleventh hour, which would have made any other potential replacements superfluous too.

But suppose the Sculls didn’t loan the works. Suppose Johns painted even closer remakes. Suppose he included them in this important museum show. And suppose he kept them after the exhibition ended, while his career went nuclear in the succeeding decades.

Wouldn’t the replacements parallel Swift’s planned re-recordings of her back catalog? Regardless of whether the Sculls went on to sell the first versions, wouldn’t Johns have had the opportunity to resell the replacements himself for a healthy price, either privately or at auction? Isn’t it even plausible that the replacements might have become perceived as more valuable than the originals, since they would have been the actual works installed in the Jewish Museum survey?

It’s all a giant counterfactual, of course. But it’s worth noting here that Guyton’s implied threat of mass-production did not buzzsaw the value of Untitled (Fire, Red/Black U) at auction. The original, but perhaps no longer unique, painting still sold for just over its $3.5 million high estimate. So much for the economics of scarcity.

All of this to say, if you’re a famous artist (justifiably) pissed off about the fact that collectors, secondary-market dealers, and auction houses are capturing the gargantuan upside on one-of-a-kind works you sold for fractions of the resale price years earlier, maybe it’s worth asking whether Jasper Johns was onto something… and whether Taylor Swift is taking it to its logical conclusion.

For the sake of your reputation, just tell people you got the idea from Jasper. Your secret’s safe with me.

[The Hollywood Reporter | ARTnews]

That’s it for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: sometimes what matters most is the will to do what the other guy won’t.

![Andy Warhol, Double Elvis [Ferus Type] (1963). Courtesy of Christie's Images Ltd.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2019/05/double-elvis-new2-660x1024.jpg)