Auctions

Who Won Auction Week? Here Are 13 Key Takeaways From New York’s Head-Spinning $1.1 Billion Fall Art Sales

From the priciest work to the top flop, here are our parting observations from last week's auction marathon.

From the priciest work to the top flop, here are our parting observations from last week's auction marathon.

Artnet News

Imagine the reaction on an art dealer’s face a generation ago if you told them that the Big Three auction houses sold $1.1 billion worth of art across just five evening sales… and analysts described the results as “sober,” “workmanlike,” and “solid but unspectactular.”

That’s exactly what happened last week across the New York headquarters of Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips. Total evening sales in those seven days totaled about $330 million less than the $1.43 billion generated in the same five auctions last year, reminding us all of what an outsize role expectations play in our interpretations of this ever-shifting market.

What lessons should stay with art-market hounds after the annual fall auction frenzy? Here are some parting thoughts on the evening sales.

Christie’s at Rockefeller Center in New York City. Courtesy of Christie’s.

Christie’s retained its position at the top of the pack with the highest grossing series of sales during the November gigaweek—although it also experienced the biggest dip from last year. The auction house has taken the title of biggest moneymaker for as long as we have been doing these recaps (this is the sixth, for those keeping track at home). This time around, Christie’s generated $670.6 million from its evening and day sales of both Impressionist and Modern and postwar and contemporary art. The newly private auction house Sotheby’s took the silver medal with a total $633.6 million, while perennial third-place finisher Phillips, which holds just one evening and one day sale of 20th century and contemporary art, pulled in a respectable $148.4 million. Phillips was the only house to increase its total from last year, a 30 percent boost from its November 2018 figure. The other two houses posted declines of around 25 percent (for Sotheby’s) and 63 percent (for Christie’s).

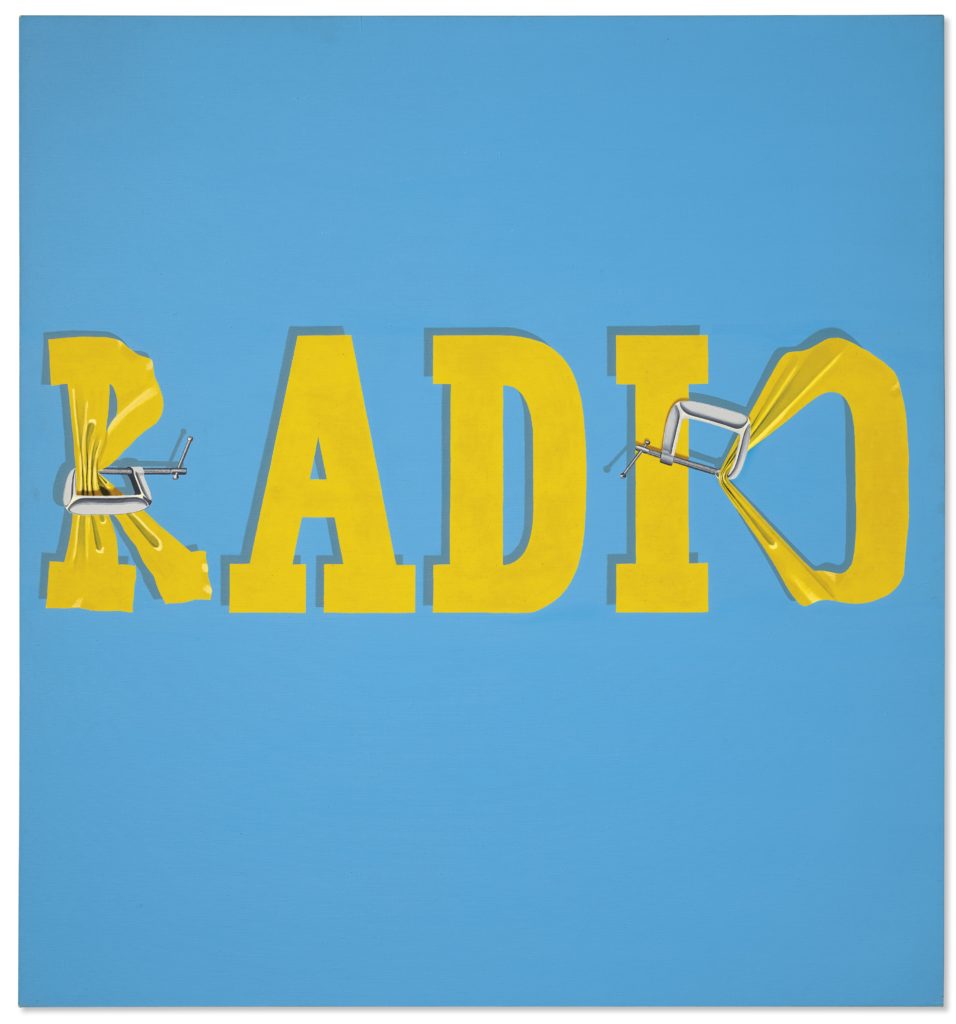

Ed Ruscha, Hurting the Word Radio #2 (1964). Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

From pursuit to presentation, Christie’s turned the dial up to 11 for Ruscha’s electric-blue word painting. Chairman of postwar and contemporary art Alex Rotter divulged during the press preview that he’d been trying to secure the work for at least a decade. Once his efforts finally succeeded, the house went all in by exhibiting the work inside a dedicated “radio room,” designed to mimic a recording booth and completed by a looping soundtrack of 1960s hits.

The efforts paid off: Hurting the Word Radio #2 grooved to a final price of $52.5 million, setting a new world for Ruscha. True, that total only amounted to a little more than half of what was paid for last November’s top lot, David Hockney’s $90.3 million Portrait of an Artist (Pool With Two Figures) (1972). But it made Hurting… the only work this auction week to sell for over $50 million, which qualifies as a certified smash in what proved to be a cautious, if still active, market.

Marc Jacobs with Ed Ruscha’s She Gets Angry At Him (1974). Photo: Victoria Stevens. Courtesy Sotheby’s.

Marc Jacobs has a long relationship with the contemporary art market, and did much to democratize it while running Louis Vuitton—the handbags designed by Takashi Murakami and Richard Prince under his watch were works of art you could sling over your shoulder, and became some of the most iconic and best-selling fashion accessories of the decade. Ahead of a move out of the West Village and into a house upstate, Jacobs decided to sell off his personal collection at Sotheby’s—including Ed Ruscha’s She Gets Angry At Him, which the designer bought while sitting in the salesroom at Sotheby’s in 2014 for $2.1 million. But when the painting came up in the same room on Thursday night, five years later, with an estimate of $2 million to $3 million, it failed to sell, with not a single bid in the room. (It was offered again at the end of the sale, and sold for $1.7 million, well below the low estimate.) The flop was even more surprising considering the record set for Ruscha the evening prior at Christie’s. Things were more promising for Jacobs during the day sales on Friday, as a Genieve Figgis painting that Jacobs bought from Half Gallery a little over a year ago sold for $125,000 over a high estimate of $35,000. Apart from the Ruscha, the 42 other lots from Jacobs’s collection found buyers, for a haul of $18.5 million—a solid total, but perhaps not the fireworks expected for top-notch works with such a starry provenance.

Paul Signac, La Corne d’Or (Constantinople) (1907) Image courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern sale on November 12 featured a vibrant riverscape by Paul Signac of Constantinople, La Corne d’Or (1907). If it looked familiar, there’s a reason for that: It has appeared at auction twice before over the past decade. When it was offered for sale in May 2008 at Christie’s New York, it realized $6.6 million. Four years later, it crossed the pond to Christie’s London and sold for twice that, achieving $13.9 million (£8.8 million). This time around, the bump in value was far more modest. The picture hammered at $14 million, right at the low estimate, and the final price, including premium, was $16.2 million. There is a good chance it sold to the presumably happy dealmaker who put an irrevocable bid on the work in hopes of winning it at a lower price. But the jury is out on whether the buyer, who made a very thin margin on the deal, will be equally pleased.

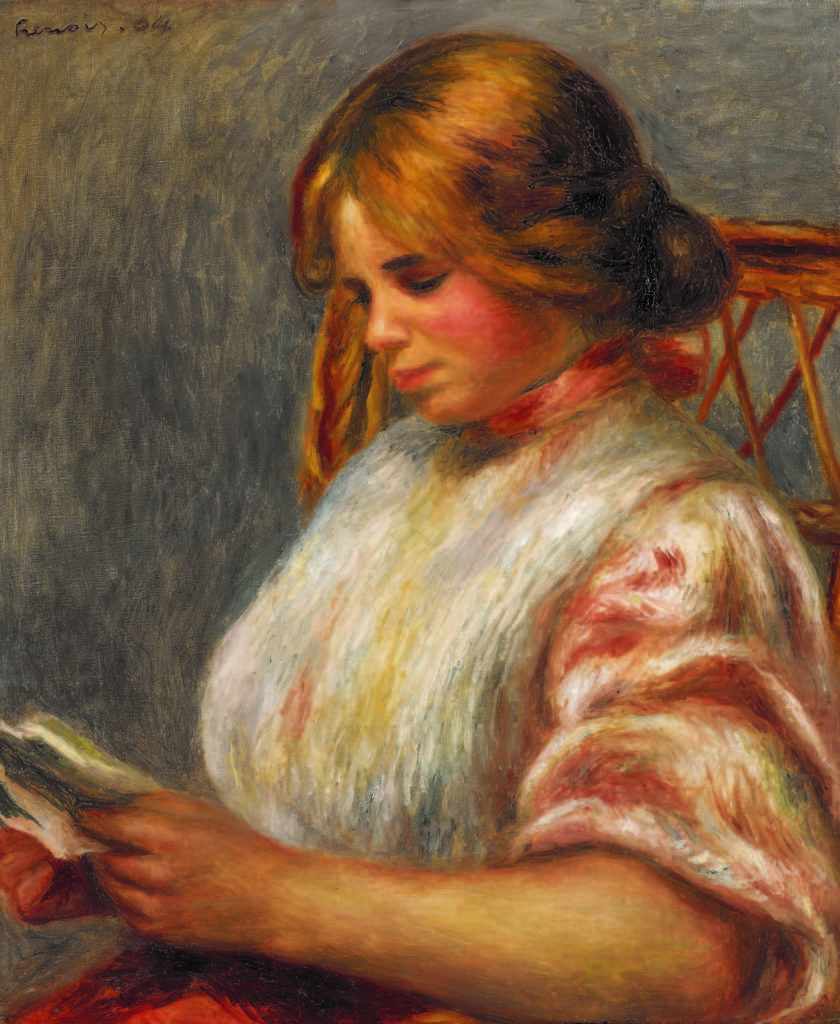

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, La Liseuse (1904). Image courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Although it would be naive to assume that collectors 103 years ago never thought about the market for the works they acquired, it seems equally naive to assume that most people buying art today will keep it in their family for generations. In contrast, this petite Renoir painting descended down the lineage of one Dr. Emil Hahnloser from 1916 to last week, when his distant relatives offered it in Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern evening sale. And while the piece sold below its $1.2 million low estimate, the $980,000 it brought almost undoubtedly exceeded even the most optimistic prognosis the good doctor ever made for its future value.

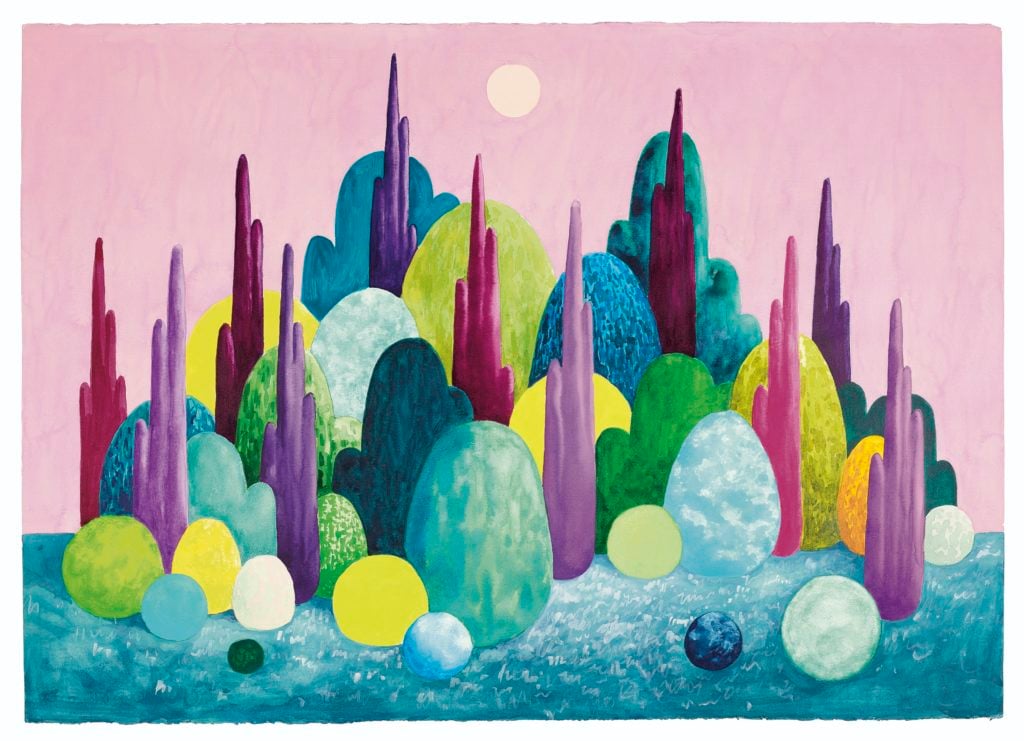

Nicolas Party, Untitled (2016). Photo courtesy Christie’s.

Advisors were shocked by the aggressiveness with which Hauser & Wirth set primary market prices for works by rising star Nicolas Party, who joined the mega-gallery’s roster in June. New paintings will cost $350,000—whereas in 2018, you could get one fresh from the studio at Xavier Hufkens for under $90,000. It’s a sign that the global gallery is fully invested in what might be its buzziest market artist at the moment, and perhaps the only artist on its roster under 40. But the price is also in line with the level set on the secondary market last week. At Christie’s day sale, a candy-colored 2016 landscape by the Swiss artist sold for $325,000 with premium, well over its $200,000 high estimate. Two other works on paper at Phillips also both nearly doubled their $60,000 high estimates. Party’s first show with the gallery will be at Hauser & Wirth’s space in Los Angeles during Frieze Los Angeles. The waiting list, we presume, has already formed.

Umberto Boccioni, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, conceived in 1913, cast in 1972. Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

At Christie’s evening sale on November 11, a rare futurist sculpture by Umberto Boccioni that was conceived in 1913 and cast in 1972 ignited a bidding war. It ultimately sold for $16.1 million with fees, well exceeding its $4.5 million high estimate and setting a new record for the artist. Its success wasn’t surprising considering how rarely these sculptures come to market. Just how rarely, you ask? Well, the previous record for a sculpture by the Italian artist was set so long ago that Christie’s had to cite the the purchase price in guineas. At Christie’s London in 1975, a buyer paid 17,000 guineas, or $41,140, for another work from the same edition.

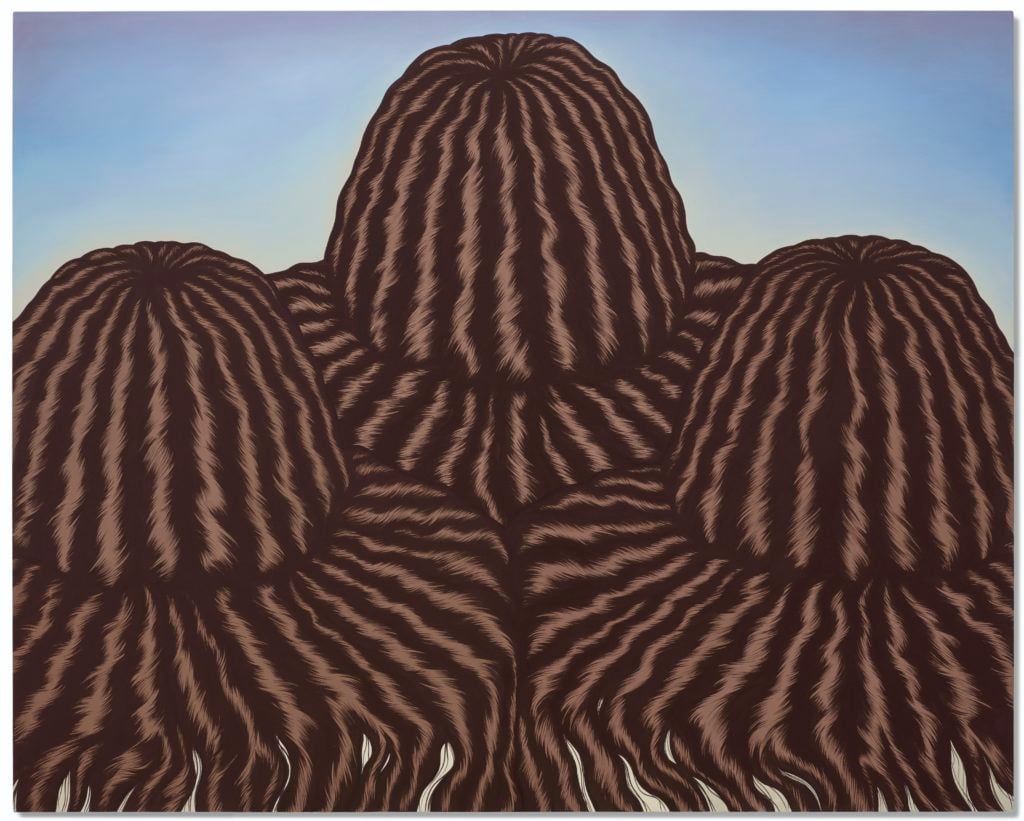

Julie Curtiss, Pas de Trois (2018). Photo courtesy Christie’s.

One could be forgiven for thinking that the feeding frenzy for works by Julie Curtiss would calm down a bit after the remarkable sale last May, when her painting Princess, estimated at just $6,000 to $8,000, ended up selling for $106,250 at Phillips’s day sale. But a few months later, even after the estimates were brought up to the high five figures, the prices exploded, and another painting sold for $262,086 at Christie’s London during the Frieze Week sales in October. Last week’s New York sales were the real test for the Julie Curtiss market, and once again, demand pushed auction prices sky-high. Within a few hours on Thursday, a work sold at Phillips for $400,000 and another sold at Christie’s for $423,000. Where will the market go from here? Sources say there are several top-quality paintings still out there, and if they don’t get traded privately in the next few months, look for more to pop up in the sales in May.

Lisa Dennison. Photo courtesy Sotheby’s.

Auctions are never entirely predictable, but Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern evening sale on Tuesday had an unusual level of excitement—and not because everything went right. During the bidding for an unusual Auguste Rodin French limestone relic, there was an extended pause while auctioneer Oliver Barker patiently waited for Sotheby’s executive vice president Lisa Dennison, who was on the phone with a client, to indicate whether she was still bidding. As the price hit $5.9 million, and with the entire salesroom looking on, Dennison calmly and quietly said, “Hold on, I lost my line.” (Yes, a nearly $6 million phone call dropped at precisely the wrong moment.) After a tense minute or two during which at least one cell phone was volunteered, Dennison and her assistant restored the connection and got the client back on the phone. Against dogged competition from private dealer Philippe Ségalot, who was seated in the room, Dennison jumped back into the fray, and called out “Six!” to indicate $6 million. One bid later, at $6.2 million, Dennison won the work for her client. It wasn’t the only technical snafu of the night: Right as Barker opened bids on the very first lot of the evening—a $1 million Picasso—the lights in the saleroom briefly went out.

Collectors Joan Quinn and Jack Quinn at the Hammer Museum’s 2014 Gala in the Garden. (Photo by Stefanie Keenan/Getty Images for Hammer Museum)

During the post-auction press conference for Christie’s postwar and contemporary evening sale, Ana Maria Celis, the department’s senior vice president, read a statement from collector Joan Quinn, who had consigned the auction’s centerpiece: Ed Ruscha’s record-smashing Hurting the Word Radio #2 (1964). Quinn, who was watching the proceedings from a skybox, revealed in the statement that she had worn a custom jacket designed by Johnson Hartig of Libertine emblazoned with the phrase “Fight Club.” The phrase was a sartorial memorial to her late husband, Jack, whose friendship with Ruscha included frequent trips to boxing matches around Los Angeles. “My family has been blessed to enjoy Radio for the last 40 years,” wrote Quinn, “and I feel like we have all won tonight.”

Clyfford Still, PH-399 (1946). Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s.

It’s not too often that a battle for a work lasts so long that you could go to the bathroom, stretch your legs, and check your phone before the hammer comes down. But early on in Sotheby’s contemporary evening sale, Clyfford Still’s PH-399 (1946) generated a protracted bidding war between two specialists: the auction house’s contemporary art head, Grégoire Billault, and Sotheby’s contemporary art head in Asia, Yuki Terase. For 15 minutes, the glacial bidding pace lost the attention of nearly everyone else as collectors began mumbling about missing their dinner reservations. The lot ended up settling with Terase’s client for $24.3 million, to sighs of relief from the room.

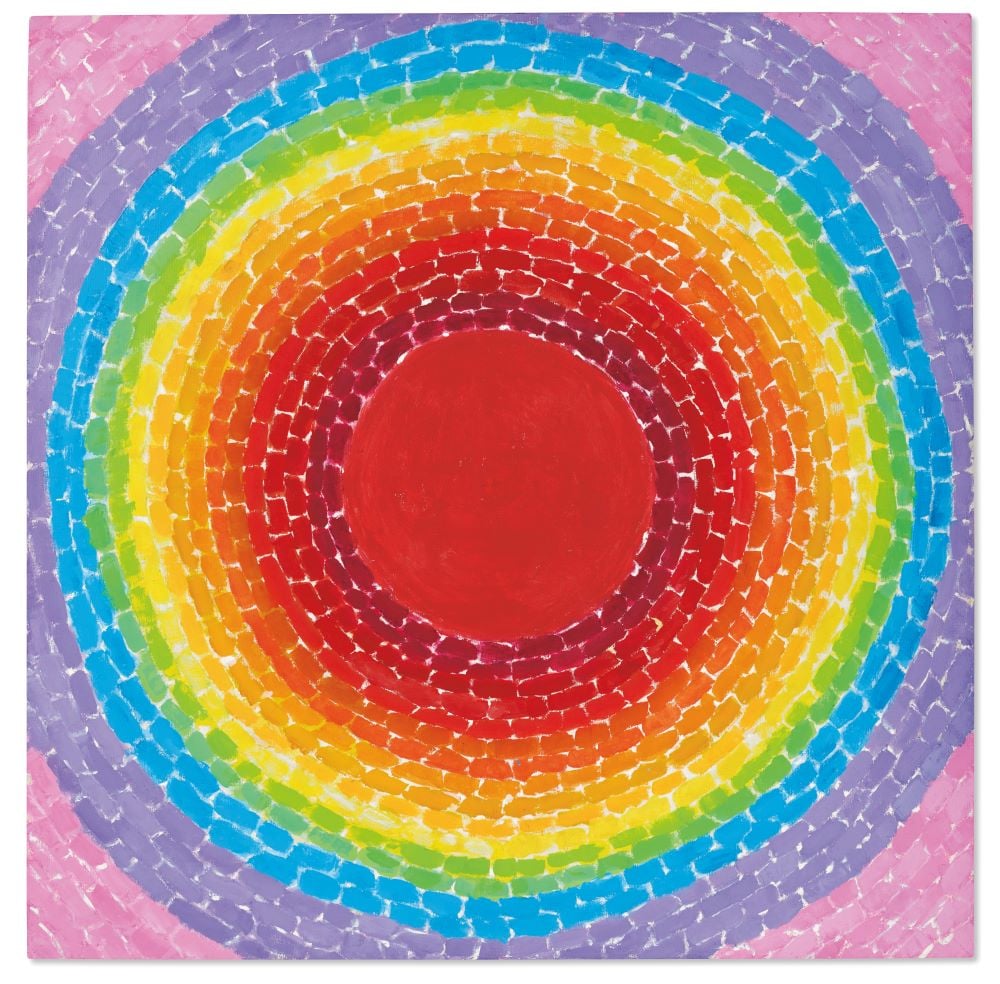

Alma Thomas, A Fantastic Sunset (1970). Image courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

This award is designed to go to the artist with the largest boost in price between their new record price and their previous record price. That disqualifies auction newcomer Michael Armitage, whose nuclear debut at Sotheby’s will be covered in our forthcoming day-sale Auction Blotter. In terms of veterans under the hammer, though, no one enjoyed a brighter glow-up this fall than Alma Thomas. Her rainbow canvas A Fantastic Sunset (1970), offered by Christie’s (and containing an unenviable provenance from Bill Cosby), established a new top result for the artist and marked her first appearance in an evening sale. At a premium-inclusive $2.7 million, the price was roughly 360 percent higher than her previous auction record of $740,000 for AZALEAS (1969), set just recently at Sotheby’s, in May.

Norman Rockwell Before the Shot (1958). Image courtesy of Phillips.

It’s no secret that Phillips auction house has been broadening its offerings after several years of focusing more narrowly on emerging contemporary names. But it was a serious leap—and a test of its loyal contemporary collectors—to place a classic Norman Rockwell in the same sale as super-hot names like KAWS, Jonas Wood, and Julie Curtiss. That bet paid off, however. The painting, Before the Shot (1958), drew competitive bidding from four top Phillips specialists. It was won by Phillips chairman and contemporary specialist Cheyenne Westphal for a hammer price of $3.9 million, handily exceeding its $3.5 million high estimate. Following the sale, Westphal confirmed the winning client was a contemporary collector who is entirely new to buying more traditional American art.