Opinion

Kenny Schachter on Joe Bradley’s Unlikely Rise to Art World Eminence

Joe has always ambitiously courted failure.

Joe has always ambitiously courted failure.

Kenny Schachter

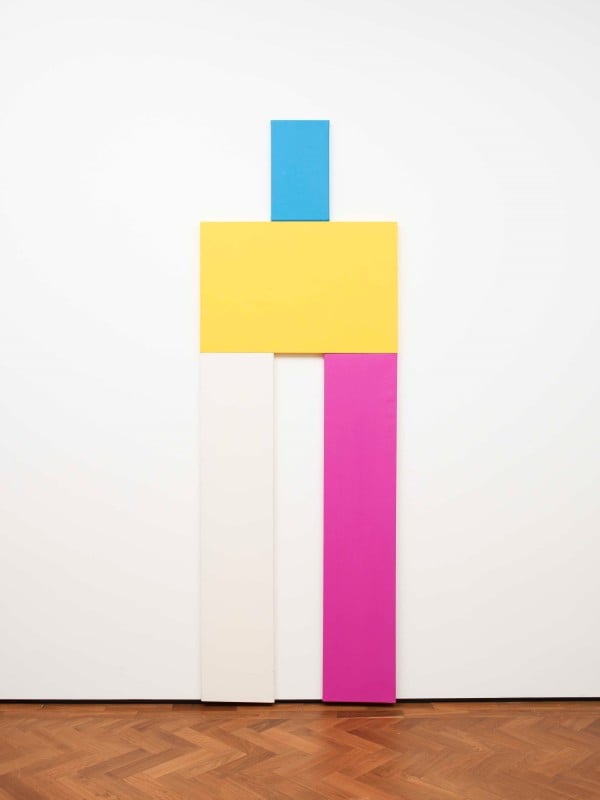

Joe Bradley, Untitled (2015).

Image: Courtesy of Kenny Schachter

Though neither of us could recall the exact circumstances under which we met (endemic to the times), I’ve known Joe Bradley since roughly 2001. I was immediately taken by the artist and his art though his work didn’t look particularly competent or well made. Maybe it was its spirit of being the wrong thing at the wrong time that I found so compelling; it was a down time in the overall market and even less favorable to new painters. After buying a fey, amateurish landscape with a wisp of a barely-there boat for a couple-hundred dollars, I jumped at the chance to exhibit the paintings.

In 2003, Bradley had his first solo show (our only exhibit together) in an upstairs project space within the little project space that I opened in New York’s West Village designed by Vito Acconci. It was a cage-like gallery with a winding Möbius strip-like skin of steel mesh that snaked from outside the front door, through the ground floor, up the stairs and along the walls and ceiling. Let’s just say that even in the best of times, it would have been a challenging context. Joe put up a valiant fight.

Interior of Kenny Schachter’s 2003 West Village project space, ConTEMPorary. Photo: Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

I’ve never been very good selling art. In spite of the caliber of the works on view, and the prices (which ranged from $1,500 to $3,000), this event was no exception. While not intended to be a philanthropic venture, the show ended up being exactly that by default when I failed to flog any of the paintings; admittedly, they weren’t overly pleasing to the eye. I bought most of them and gratefully still own them.

An aside: taking a stab at impresario-ism, I arranged a night of live emerging music at Capitale, an event space on the Bowery that’s owned by a friend, and included Joe’s band Cheeseburger. After being unceremoniously thrown out in the midst of the packed performances because of the flying bottles and slam dancing (I thought that was an encouraging sign), I got a call from Eminem’s label asking for a Cheeseburger recording. I excitedly informed Joe and got my hands on a CD only to be informed by Eminem’s people that it was the most poorly made demo they’d ever heard. Bingo! In his music, as in his art, Joe succeeded at flopping with flair, fanfare, and flamboyance.

Over the course of the next ten years or so, Joe and I lost touch—I didn’t want to bother him as he began to succeed commercially; and did he ever. Last November, his painting Tres Hombres fetched $3,077,000 at the Christie’s New York post-war and contemporary evening sale. We reconnected when he came to stay with me in London over the past summer with his three kids and his architect wife, Valentina.

Joe Bradley, Cosmic Return (2003). From the first exhibition at Schachter’s West Village project space.

Back to the art of the initial 2003 outing: there was a shiny silver monochrome resembling a panel of a Warhol diptych put together haphazardly with thick nautical rope affixed around the edge of the circular canvas. This was grade school art gone awry. A more glaring example was the garish black and gold finger painting (that’s what it looked like) from 2002 entitled We All that recalled Joan Mitchell sloshing paint while sloshed.

We All, and works like it, gave rise to the much sought-after and admired Cave paintings, the name for Joe’s smushy abstractions, composed of bled blocks of colored oil stick physically applied to unprimed canvases à la Richard Serra’s works on paper. These are passive-aggressive, assertive paintings referencing not so much the body but rather its residues. In the same way Mark Grotjahn exhumes tropes of 1950s abstraction in a contemporary fashion, Joe hits up abstract expressionism for an update—a pair of historical grave robbers.

Joe Bradley, We All (2002).

Image: Courtesy of Kenny Schachter

The Cave paintings bring to mind Mike Kelley’s forlorn, castoff stuffed animals, as dirty and abject as a Freudian shit stain or puddle of vomit, but simultaneously beautiful and covetable. As Dubuffet looked at mental patients and outsiders, Joe examines the crazy within.

Paul Thek was an analogous artist, awing viewers in many media (with difficulty gaining recognition in any) who purposefully set out to make makeshift “bad paintings” (his term) later in life because he was certain that that was what the market wanted, while concurrently mocking it. He died destitute having been too far ahead of the curve.

The latest works of Joe’s that I’ve seen this past fall in his New York studio are a distillation of the Cave paintings, pieces that are starker, with white grounds (instead of exposed canvas), evoking previous bodies of work along with quotations seemingly out of left field from artists including Adolph Gottlieb.

Joe Bradley, Untitled (2006).

Image: Courtesy of Kenny Schachter

Back in 2003, we also exhibited monochromatic muslin and linen panels that would come to comprise components of the later Modular works (the “robots”), reduced to their constituent elements. Of course they were shoddily assembled with fabrics of questionable quality. Besides the figurative works, some painted others created out of store bought vinyl, there were boats composed of shaped primary colored canvases. It was like Ellsworth Kelly became a stand-up.

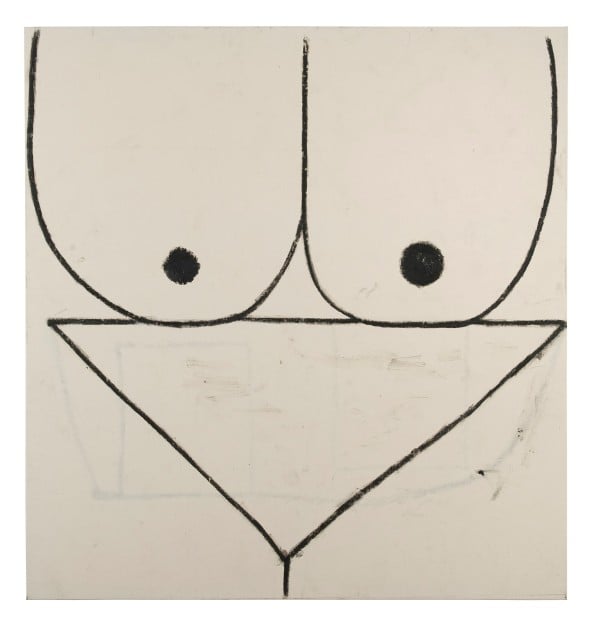

Joe Bradley, Untitled (Pink Schmagoo) (2015).

Image: Courtesy of Canada Gallery.

Among Bradley’s most unashamed affronts to art are the “Schmagoos.” Taking their name from the slang term for heroin, these crude drawings on canvas offer toothy smiley faces (my kid’s got it tattooed on his forearm), stick figures, crosses, an un-super Superman insignia, and fishes. These misleadingly simple and beguilingly childlike renderings in oil stick deploy a lot of kid play and deadpan humor to poke fun at the self-serious art world. Most insolently, these paintings question virtuosity; is it mastery of technique or a clever de-skilling of process?

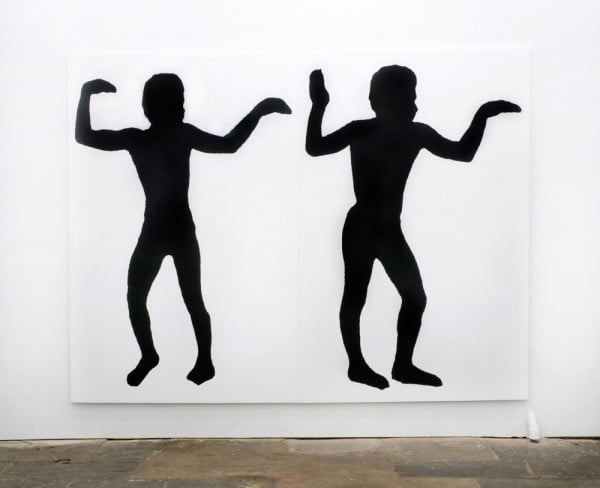

Joe Bradley, Untitled (2011).

Image: Courtesy of Kenny Schachter

The Silhouette paintings incorporate the Egyptians, which were effectively unsellable at the time. Thankfully most stayed together and went to Swiss collector Michael Ringier, owner of Monopol Magazine (for whom I also write). You can’t like it all, you shouldn’t—I’m not sure even Joe does—but these works grow on you over time. They also remind me of the video for “Walk like an Egyptian,” a song by the ’80s band the Bangles. The paintings are outlines of figures with hands extended in opposing directions as if seeking backhanders from both sides (like art dealers). Joe shares similarities with practical jokers—with a bit of nihilistic prankster-ism, he pulls the rug out from under viewers while being comical and engaging—he unsettles and wonky-fies painting.

From his very beginnings, fumbling around a dark room, Bradley still managed to create a focused, principal body of paintings. Elements of that early work can be seen in every series that followed; he described the experience of our show together as his Rosetta Stone. I’m not sure this was apparent to anyone at the time, let alone the artist. These works in total looked terribly out of place…well anywhere; we hadn’t a clue about the mushrooming that would engulf Joe’s career the next decade.

Unlike Matthew Barney and other neo-conceptualists, with Joe, the symbolism is lodged in paint. As Marshall McLuhan might have phrased it (or Clement Greenberg if he smoked pot), meaning is (embedded) in the medium. Imagine the task of differentiating yourself as a painter in today’s post Zombie Formalist era. Not to mention that Joe was dissuaded from showing his Cave canvases at the MoMA exhibition “The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World” (from December 2014 to April 2015) because they had been copied too successfully by another artist in the show (after gratuitously imbuing them with social baggage).

The Joe Bradley tattoo on Schachter’s son’s arm.

Money is no substitute for the absence of critical response and there is far too little about Joe’s work from the press in New York, Joe’s hometown since he began exhibiting. As he continues to fetch higher prices at auction, he never makes it easy for himself (with critics, anyway) with his ongoing painterly shenanigans. And now, for better or worse, he has hopped aboard the Larry G. bandwagon. But fear not. Joe is a bawdy, incorruptible soul. He would sooner sabotage himself before surrendering to the market Mephistopheles; his constitution wouldn’t and couldn’t allow it. You get the feeling that Joe is as repulsed by accomplishment as much (if not more) than enthralled.

I think Joe works from the stress of having to produce, of being on stage contending with expectations and the pressure to make paintings endlessly afresh. Like a chameleon, his greatest strength is not getting stuck in a single mode of working, and it’s been a remarkable effort to observe. A retrospective of his work would look like a group show. Joe wangled his way into the game by the force of his doggedness and stop-start direction changing. But like an actor with performance anxiety, he always seems to follow the adage that the show must go on; why not kick it off at the biggest theatre in a town near you: The Gogo.

Joe Bradley, Untitled (2009).

Image: Courtesy of Kenny Schachter

The early paintings were minimal and reductive but there was always something slightly subversive about the way a given piece was painted or stretched. The works effortlessly shift from the scatological and puerile to the formal and austere. Nothing’s changed in that regard. Joe never toed a political line or espoused an underlying social agenda. It’s art pushing the notion of acceptable taste in relation to what paint on canvas could be. The line drawings, mushy abstractions, and robots are a provocative finger (or two in the UK) to the practices of both figuration and abstraction.

I am a sucker for good-bad paintings from late Picasso and Philip Guston to early 1980s Donald Baechler paintings. Joe speaks with them all. As a person, he’s humble, down to earth and more concerned with museum support than with commerce. His modesty is rare enough in the world, rarer still in the art world. He almost seems to physically resemble his work, sensitive and raw, yet removed and inscrutable.

Joe Bradley’s art is whimsical, offhanded, not serious; but at the same time deadly earnest. Joe has always ambitiously courted failure, from his early music to his paintings; he has fought professionalism in every sense that the word “conventional” conjures. At the expense of sounding corny, Joe’s work is restless, teasing, and self-deprecating. It mines and undermines art history, though I don’t think he’s about chipping away at it. He loves and respects art too much, probably more than he does his own health and wealth. I get the feeling his pursuit is as much to surprise himself as it is us.