This story has been updated with a correction. Please see the full correction appended at the end.

As the beaches swell with sardined sun worshippers and pathetic partygoers, and as COVID numbers dramatically (and proportionately) re-increase, I can only imagine the fall we are going to literally fall into. Speaking of the general state of escalating nuttiness in the world, art dealer Inigo Philbrick was arrested while obliviously strolling the markets in the Republic of Vanuatu with his girlfriend Victoria Baker-Harber (I can’t confirm if they were wearing their masks at the time) and their stray dog, then whisked away by the FBI in a Gulfstream jet—and not, sadly, with the lavish in-cabin services he was accustomed to.

I can relate (two reliable sources have told me so, anyway) that, along with a lengthy prison sentence, Philbrick and Baker-Harber are expecting their first child. (He has a daughter with his previous girlfriend Fran Mancini.) I’m not sure if saying this will be seen as a violation of the cease-and-desist order Victoria’s law firm served me with last week, so let’s just keep it between us.

I understand the concept of walking around masked-up, and I never leave home without mine. But it is admittedly kind of gross, since they inevitably come to smell like a dirty diaper. Once again, I was a wee little complicit in some reckless behavior, this time when I hopped on four planes—and finding flights today is as hard as the time before the onset of the ubiquitous commercial travel in the 1950s—to release prints and make a speech at Johann König’s Berlin gallery. I just had to know what it felt like to be art-alive again. I’m such a pathetic case, I actually got goosebumps in my hotel lobby when I bumped into gallerist Thaddaeus Ropac. (I never said I was normal.) I hadn’t stayed in a hotel for the four months since Frieze/Felix in Los Angeles in February, the longest stint of abstinence I can remember.

It was Ropac’s first art outing as well, and at breakfast the following day he mentioned that he hasn’t made a single member of staff redundant after a number of very strong years of business. (With Adrian Ghenie’s paintings at $1 million to $1.2 million a pop on the primary market, and with Kiefers and Baselitzes flying off the walls, it makes sense.)

On the other hand, it was only announced last week that David Zwirner laid off 20 percent of his workforce—a move that has as much, if not more, to do with his expansionary real-estate endeavors as with the constriction of the art business. Pace, suffering a hangover from grandiose building-envy themselves, also instituted significant staff reductions after leasing their gargantuan new headquarters (unlike Zwirner, who owns his new space) and fitting it out with what was called “an adaptation of the campus model favored by Silicon Valley tech giants like Facebook, Apple, and Google”—only minus the revenues of those tech giants.

The new Pace gallery’s outdoor sculpture terrace before its opening in September 2019.

Nevertheless, that hasn’t stopped Pace from extending a job offer to legendary downtown dealer Gavin Brown, who himself moved uptown to West 127th Street in giant rental digs done up at significant expense—an act of wishful thinking, or hubris—with the hope that the art world would follow. It didn’t. After losing Avery Singer and other artists from his stable in recent years (he doesn’t have a good eye; he has a pair of great ones), Brown was entertaining the offer at the time of this writing—surely a potent sign of a wave of closures and consolidations to come.

A few words on the auctions last week—okay, more than a few, I don’t do brevity. Black lives have only seemingly begun to matter in the world, but not in the auction business, and far from enough in the art market. Though women have made strides, including at Sotheby’s and Phillips (and Christie’s sale is next week), Black artists have further to go. But don’t be fooled: studies have unequivocally shown that art by woman and artists of color costs less. Period. The auction houses remain whiter than the two-dozen paid attendees at any given Trump rally. I’ve never seen an auctioneer of color or specialist manning (or woman-ing) the phones at a sale.

Christ, even the first auction house exclusively devoted to Black art is white-owned (by Thom Pegg). Francesca Lisk, Sotheby’s newly created Chief Talent Officer—sounds like nomenclature from Disney Land—was formerly at the Brooklyn Museum, where she had responsibility for implementing the museum’s diversity, equity, and inclusion program. She’s got her work cut out for her in the same role at the auction house—to put it mildly.

Enough has already been said about the online format of the sales, which to me resembled televangelism more than anything—cheesy, kitschy, creepily messianic moneymaking at its finest. I missed the art handlers, clad in white gloves (even the gloves are white) and Sotheby’s-branded aprons, spinning around on a life-sized lazy Susan that showcases featured lots during sales. Did you know Thomas Jefferson was said to have invented the lazy Susan? According to the internet, it was “because his daughter complained she was always served last and, as a result, never found herself full when leaving the table.”

Sotheby’s salesroom in New York during its June 2020 evening sale. Photo: Sotheby’s.

Sotheby’s sale lasted five hours, a kind of horrid endurance art, and was clearly intended to be an American undertaking from the get-go. The sales began at 6:30 pm EST, 11:30 pm BST, 12:30 GMT, and ended at 11:30 pm, 4 am, and 5 am, respectively. Asia is 12 hours ahead of New York so, other than waking early, that market had an easier time of it. I am a fan of Artnet News’s Tim Schneider, but he kind of got it wrong in his piece sub-headed, “Our columnist considers how the European Union’s pending ban on US travelers puts the stateside art business at a unique disadvantage.” But I beg to differ: the art business in the States continues to dwarf the dwindling Euro market (though Paris is still a bright spot), with Asia in distant second place behind America, in spite of brutal crackdowns by Chinese authorities.

A sign of the pandemic of boredom (please excuse my inappropriate humor) and waning attention spans that quickly set in? One specialist liked my Instagram posts of the proceedings in real time, while another asked if I was amused. “Yeah by your hairdo,” I shot back, to which he deftly replied: “It definitely wasn’t camera ready.” The new state of the online art business: TV entertainment without entertainers (or entertainment for that matter), where nothing moves but money.

Forget Bitcoin, there is something better: art and cash have all but merged these days into a new currency. A major LA dealer summed it up: “Business overall is so good it sort of makes me speechless.” And the auctions, albeit diminished in scale from years past, were sound evidence of that fact.

I can reveal that the record-breaking Basquiat work on paper that fetched $15 million at Sotheby’s was sold by young French private dealer Cyril Blot-Lefevre, on a $9 million guarantee—an assuredly tidy profit despite giving away a chunk of the upside after a 20-plus year holding period. The houses assumed much of the guarantee risk during the spate of auctions, a necessity in these ridiculously unpredictable times. I asked a scion of an Asian billionaire, usually among the most proactive guarantors (if not the most), if the family was active this sale cycle, to which she replied: “No action… promise. One of the few times I could say this without lying ?.”

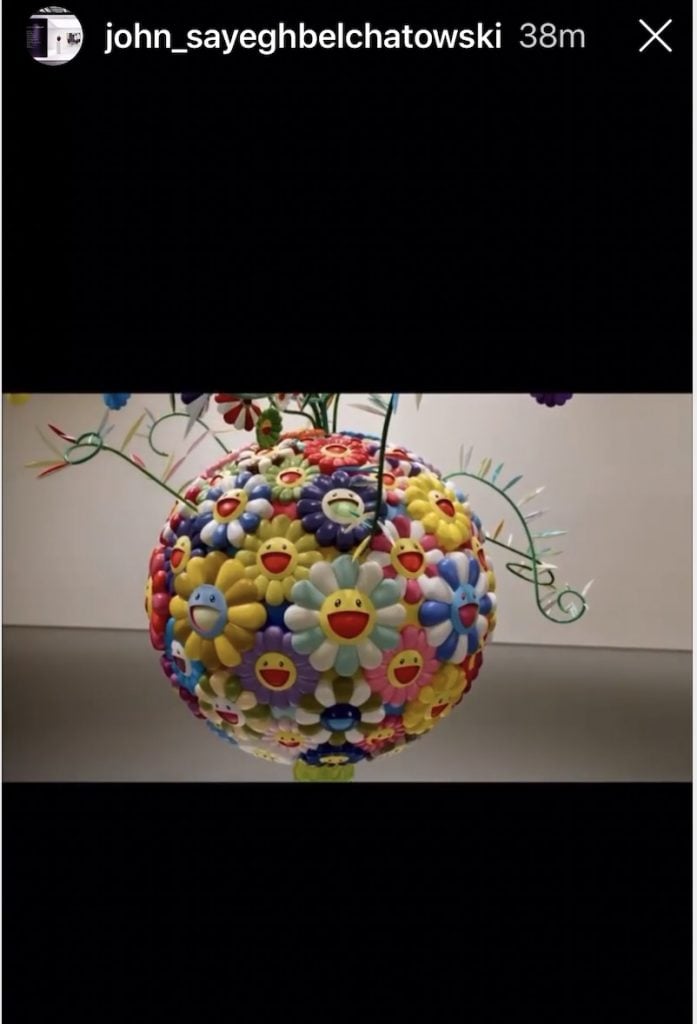

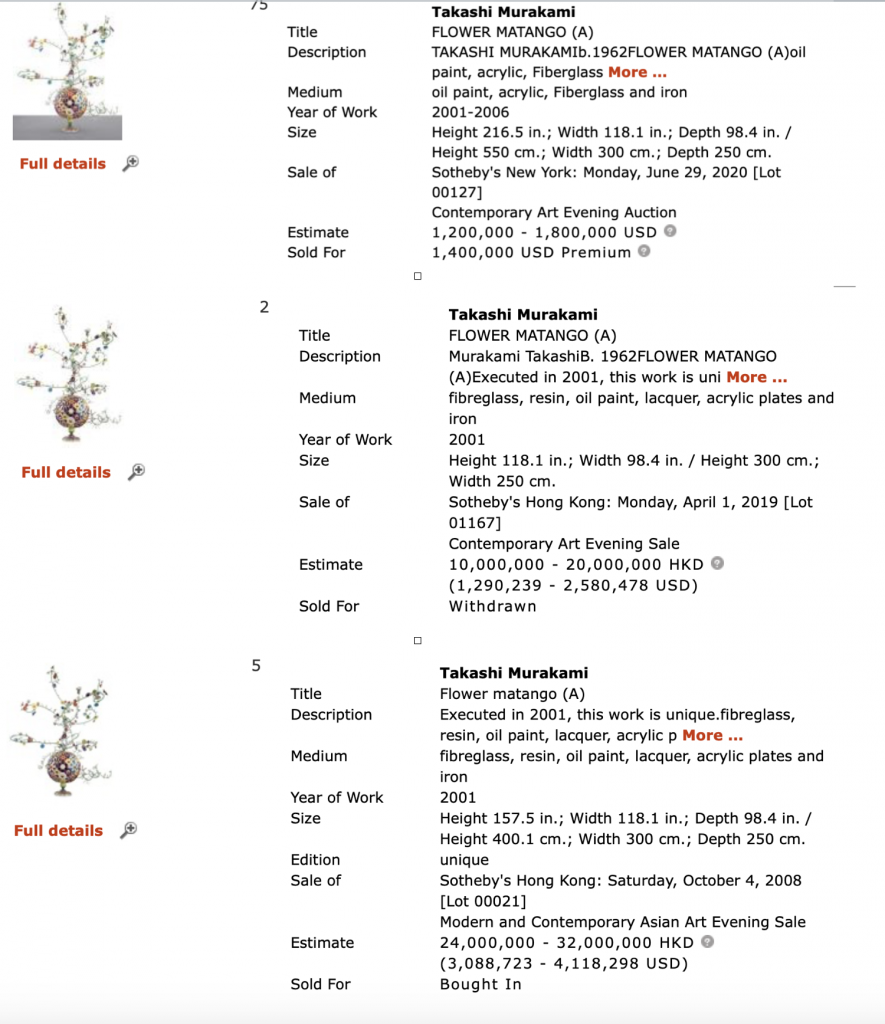

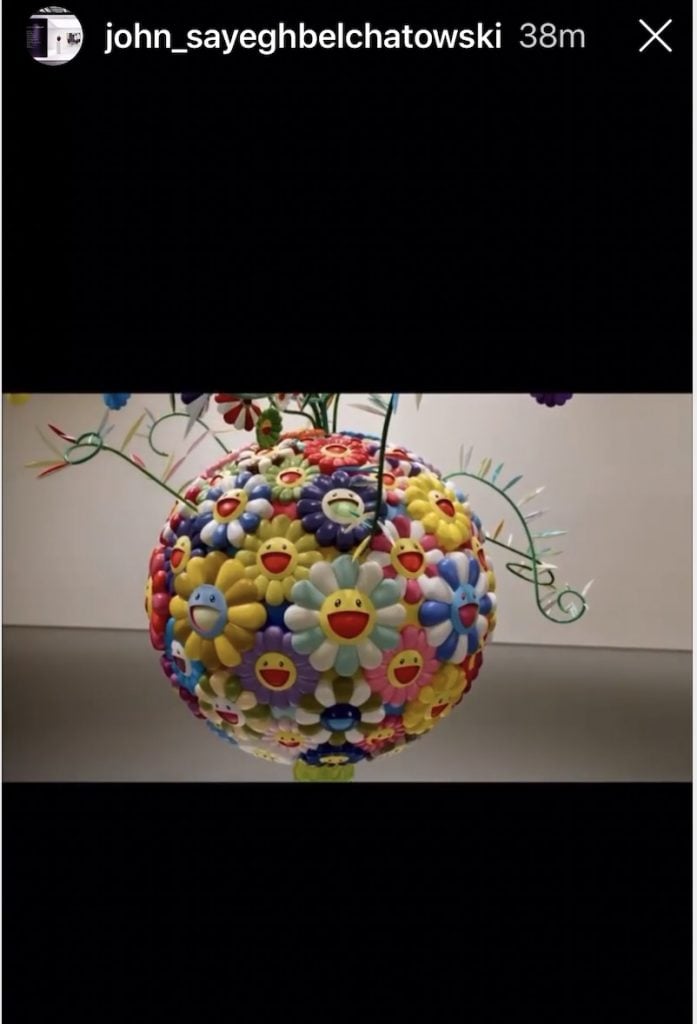

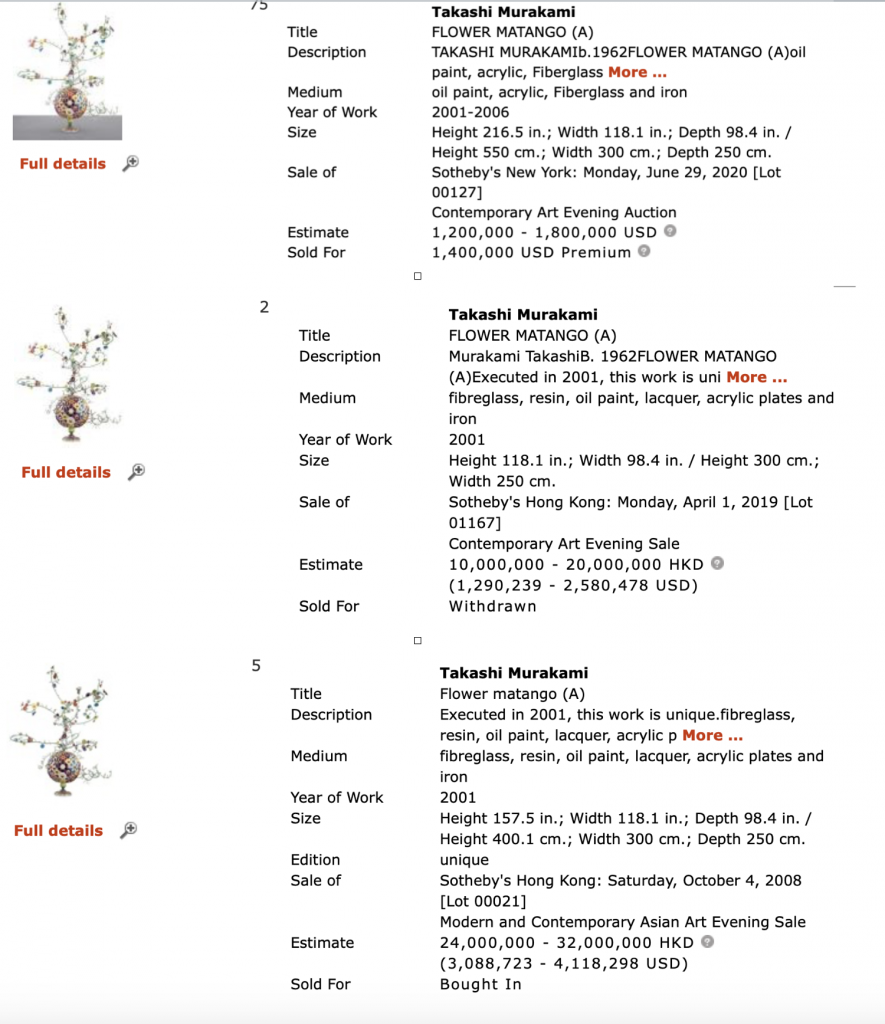

My friend John Sayegh-Belchatowski, who sometimes employs a few choice words to describe me due to my reporting, and who is a regular Sotheby’s buyer, seller, and guarantor—usually simultaneously—was probably the seller of a Murakami sculpture that was on the block for the third time, having previously been bought in (estimated at $3-4 million in 2008), withdrawn, and finally sold for $1.4 million on an estimate of $1.2 million to $1.8 million—no easy feat when the artist’s market is as down as his personal finances are said to be. Don’t shed a tear for Murakami’s alleged impending bankruptcy as expressed in his recent post on Instagram, where he’s usually seen striking more clichéd celebrity-filled selfie poses than the Kardashian clan.

Right to privacy? Pff. We give it away voluntarily, day in and out.

I’d gather Sayegh suffered a loss or at best broke even on the Murakami, and was happy to do so. (You can’t win ‘em all.) He often posts artworks on his Instagram account that he has an interest in—how can anyone complain about the lack of a right to privacy when we give it all away voluntarily? He is said to be in possession of a fat line of credit at Sotheby’s, which no doubt contributed to him getting slammed with Basquiat’s Pollo Frito for $25 million in November 2018 on a guarantee that didn’t pan out.

Going once (bought in), going twice (withdrawn), going again… sold (but at a loss?). Courtesy of the Artnet Price Database.

Don’t get me wrong, I have nothing but respect for the level of commitment and risk he frequently undertakes. When I asked, John confirmed the urban myth that ages ago he bought a Rodin plaster at a flea market in Paris that was accompanied by the French statutory right to edition copies of the sculpture and subsequently made a fortune doing so, enabling him to abandon his previous career selling carpets and enter the fray of the art market. My dad was in the carpet business too— that must be why we get along.

When it comes to flipping, Phillips has spatula-ed more than McDonalds. I don’t have entirely clean hands in the game, having engaged in the practice myself, but I have a lot of skin and blood in it from 30 hard-fought years. I know its anti-laissez-faire, but a moratorium of four to five years before art can be resold wouldn’t be the worst thing.

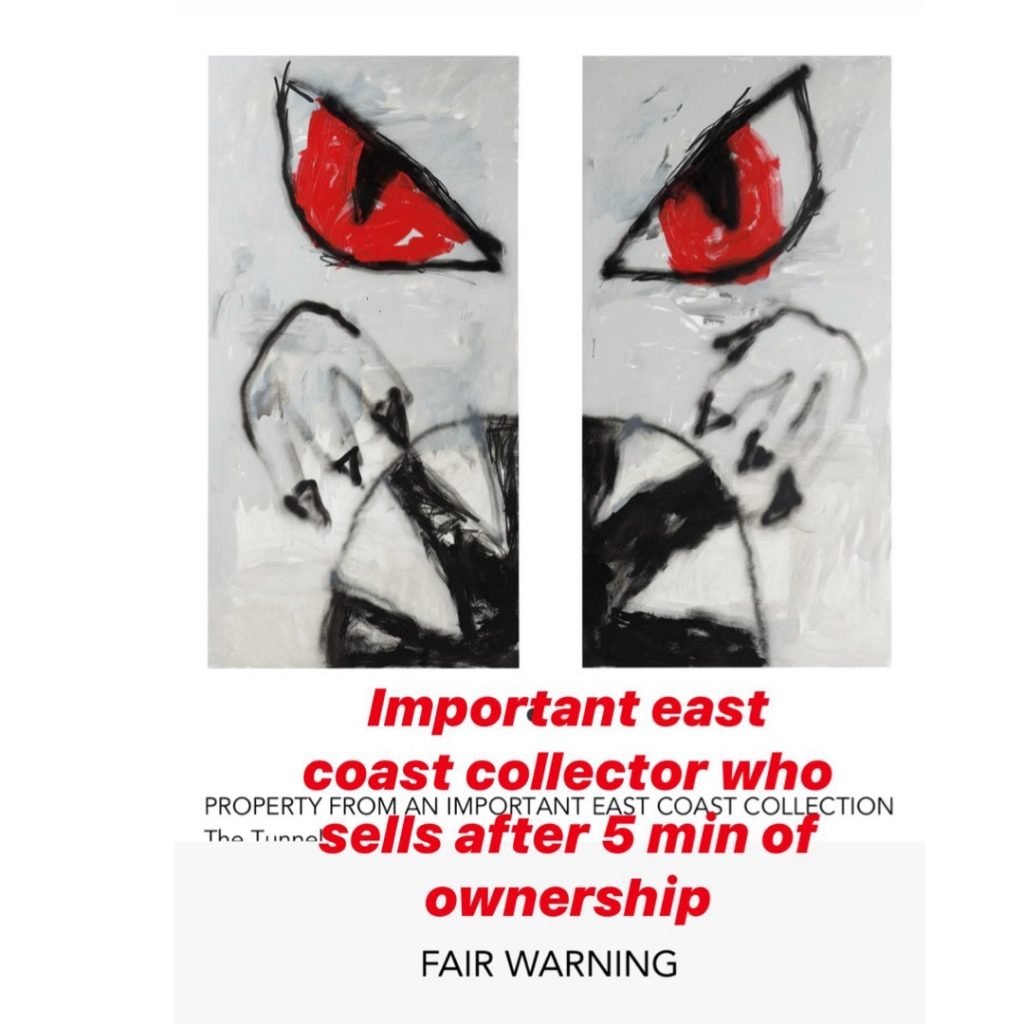

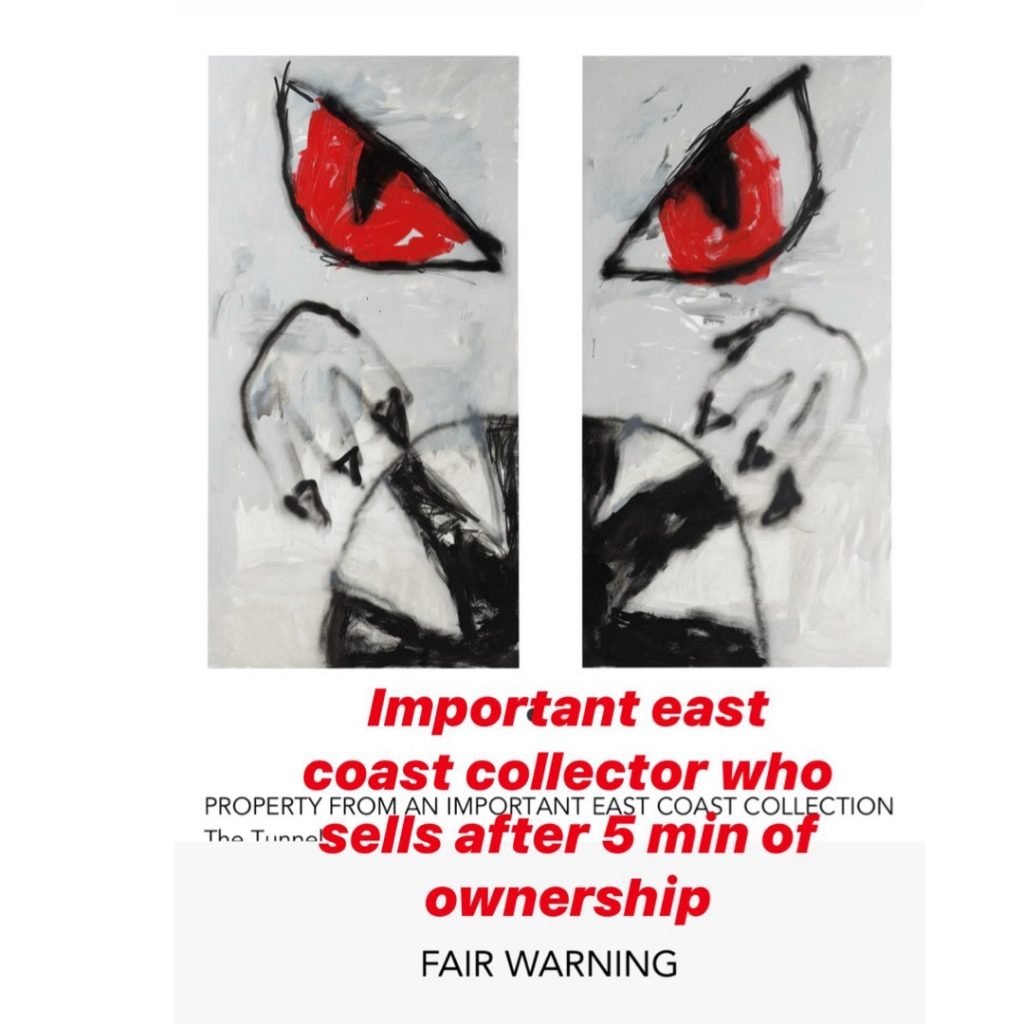

Examples of the whipsaw turnaround in paintings sold by Phillips are the number of works dated from 2017 to 2019, the house’s sweet spot. Both paintings by Amoako Boafo, which sold for $668,000 (on a $50,000 to $70,000 estimate), and Robert Nava, which fetched $162,500 (on a $40,000 to $60,000 estimate), dated from 2019 and had already been resold more than once in their brief lifespan—the Boafo no less than four times in a year! That surely makes it fit for the Guinness Book of World Records.

The aforementioned Boafo was re-re-resold after only recently being purchased from Sotheby’s private treaty for $200,000—house-to-house complicity in short term, short-sighted churning. The caption for the work should have read: PROPERTY FROM AN IMPORTANT FLIPPER. Phillips might try auctioning futures in paintings that haven’t been painted yet.

When it comes to flipping, Phillips gives McDonals a run for its money. Illustration courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Buying to sell, without so much as setting your eyes on a work, is the art-world equivalent of playing hot potato. The question is who gets caught holding the goods when the music stops (and bottom drops out) and then ends up with a warehouse full of unsellable art to show for it. Nava responded to my Instagram post on the subject by saying, “It wasn’t my best work.” You don’t encounter such forthright humility in the art world too often (besides from me, ha). At some point over the last 25 years, there was an explosion of trading activity; art shifted from an aesthetic pursuit to an asset class, and, along the way, the art got separated from the art market. In the most brutal and reductive sense, markets have no motivations other than opportunism and greed. It’s human nature.

That is, unless it concerns my own work—someone tried to flip a piece of mine last week. They offered it back to me… for free. Ugh.

Update, July 9: This article previously incorrectly stated that Jeremy Larner had been involved in the purchase of a painting by Amoako Boafo from Sotheby’s and its subsequent resale by Phillips. Larner is neither the purchaser nor the reseller of the painting, Joy in Purple. The passage has been revised and we apologize for this error.