In his Aesthetics (1835), the philosopher G. W. F. Hegel published a compilation of university lectures on fine art, stating: “For us art counts no longer as the highest mode in which truth procures existence for itself (nor does it satisfy our spiritual needs).” Arthur Danto took this position to its logical conclusion with his 1996 book After the End of Art, using Warhol’s Brillo Box as a jumping-off point to signal that pretty much everything that could be done had been—from classicism to the crass commercialization of art. I’d suggest they both got it wrong, even taking into consideration that Hegel (or Danto, from my cursory research) never visited one of the 17 iterations of Art Basel Miami Beach.

Miami is as good a place as any to test this point, a city that culturally comes alive (no easy stirring) during Basel Week, inciting ancillary projects of a spectrum ranging from a million other fairs and parties to a “Mike Tyson Inspired Art Exhibition (Invitations and Tables Only).” Tyson’s event was to raise awareness of his $40 million California marijuana-themed ranch—call him Mike, the Marijuana Medici. Tyson famously stated in the past that “everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face.” I think he’s better suited to be a dealer than an art impresario. In fact, he’d be ideal to help collect some outstanding Stingel proceeds.

Forget the official VIP shuttle—there’s no reservation required in the K car, and don’t ask me why (as a dealer did). There’s no concept—it’s Miami Beach! With the kind assistance of artist/dealer/writer of his own right, Joel Mesler of Rental Gallery. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Art reflects our time, socially, politically, economically, and technologically, and that makes it history made flesh; nothing can or will halt it, not even Tyson and his formidable entourage. Staying abreast of it is also a young person’s game, so swiftly does it shift, and perhaps that’s what stultifies the judgments of generations that can’t keep up. Change can be hard to swallow. But let’s not kid ourselves, it’s far from the end of anything—but it is, unassailably, a bloated period of excess, inanity, and the shallow monetization of all things art.

I had to leave Miami after less than two short days for yet another family emergency, the details of which you wouldn’t believe if I told you; well, you would, which is why some things are better left unsaid. Topsy-turvy, to put it mildly, passes for mundane in my household, what’s left of it, but I promise there’s no social-services file compiled on us yet (just a few police and fire reports). Everything is okay and, though I missed NADA, which I always appreciate, and Young Thug at the Nautilus Hotel (where I installed an art project of my own), I was able to catch the main fair, albeit in speed-dating mode. Less than 90 minutes is nowhere near the hours necessary to see and properly digest it all. I had an unusual case of going and having FOMO simultaneously—I went but only had a taste, and while I didn’t get my usual pricing or eavesdropping intel, I got enough to form a firm impression and opinion… surprise, surprise. But, as sad as it is revelatory to admit, I genuinely missed what I missed.

Ask your kids! Young Thug at the Nautilus Hotel in South Beach (the show had to go on without me due to foreseen family… issues). Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

The circus that is Art Basel Miami typically starts on the security line at the airport and continues to the beach. This time was no different, but the crowd was weighted towards dealers and auction-house personnel than collectors, versus years past. Ugh. I wonder if that translated to fewer overall sales. (I’d gather, yes.) Don’t bother asking anyone participating in the fair about results—they’ll make Trump appear to rival George Washington in the transparency department. (Trust me, I’ve spun many a tale to Bloomberg from the other side of the aisles.)

The best works at any given fair are presold, the equivalent of auction guarantees—they should introduce the fairantee, where you buy off the PDF before any given Basel and split the upside above your pre-purchase price. The brief time I was able to steal away for a walk, I saw a dealer smoking a Juul and talking on the phone while running—we may not be the most trustworthy, but we can multitask like a motherfucker.

Art Basel Miami’s parent company, MCH Basel Exhibition, established in 1916, stages some 40-plus fairs a year, including Bricklive—which is not building-supply expo, but rather an event promoting Lego sets. Besides its scale, another thing MCH has going for it is the fact that it’s not embroiled in a geopolitical catastrophe like, say, Frieze is. Earlier this year, Endeavor, the majority owner of Frieze, took a substantial $400 million investment from Saudi Arabian Crown Prince Muhammed bin Salman, via the gulf state’s public investment fund—the kingdom’s major sovereign wealth vehicle—before the assassination of Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi. Endeavor said it was looking into severing Saudi ties and unwinding the investment, yet that still hasn’t been effectuated at the time of this writing.

It’s a wrap: giving a new architectural life to my artnet News articles, in this case partially wrapping the lobby of Miami’s Nautilus Hotel on South Beach. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Said Adam Lindemann in his 2011 New York Observer article “Occupy Art Basel Miami Beach, Now,” “why should I be seen rubbing elbows with all those phonies and scenesters, people who don’t even pretend they are remotely interested in art?” He’s found the perfect alternative in “The Art of Blockchains,” a one-day conference he organized combining art and tech talent to showcase startups in the crypto-blockchain space. I am beginning to long for the end of history.

Though Lindemann (a crypto investor) stated unequivocally that nothing was being pitched for sale, a friend told me she was offered an investment in a hot commodity the same way a collector gets the opportunity to buy a hot artist—by being handpicked. Galaxy Digital, the market’s biggest public funn-e-money investment vehicle, recently took a dive on bitcoin’s plunge. But maybe Adam is onto something—from Basquiat to Bitcoin, he certainly knows how to make a buck. But the promise of a fragment of a Kenny Scharf painting (made in situ during the proceedings) for every attendee went unfulfilled after a bum rush ensued (as reported by artnet’s own Tim Schneider). Was the Scharf indicative of unfulfilled promises to come in the sector? Let’s see.

Much is said of fair floor plans—the geographical tug of war over which galleries are allotted the most strategic and covetable real estate. The process is said to be undemocratic and problematic, mainly by those with shitty spaces (or too much free time). Is it not blatantly clear that a raw economic hierarchy is at play where success breeds success, and for a reason? Have you ever visited a booth of Larry G? You can take a bite out of the atmosphere it’s so thick; the gallery should bottle and sell it, as if he needed any more cash. Why? Because Gagosian jams together a dynamic combo of contemporary and rarer, historical material, often of the highest quality, time and again.

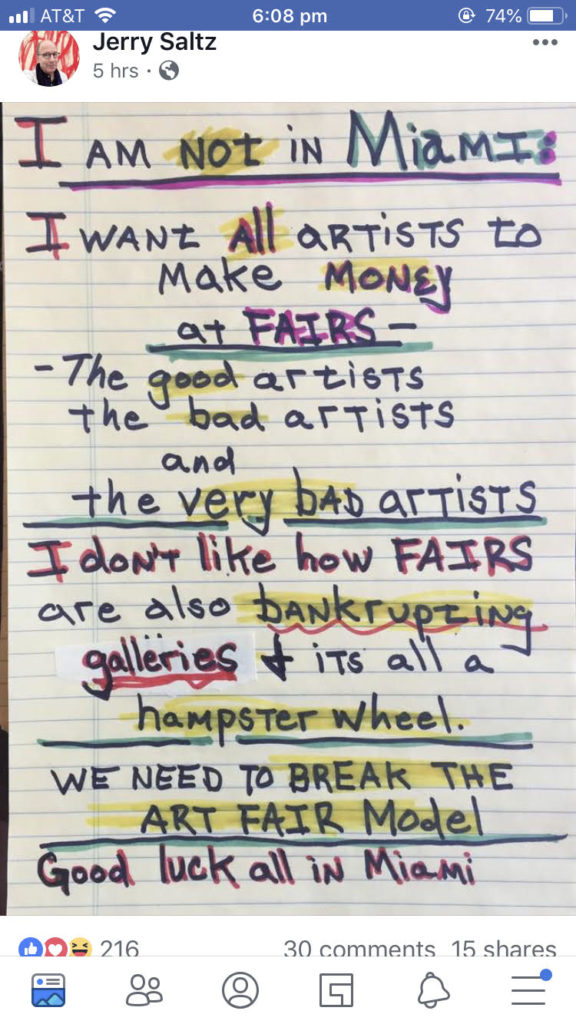

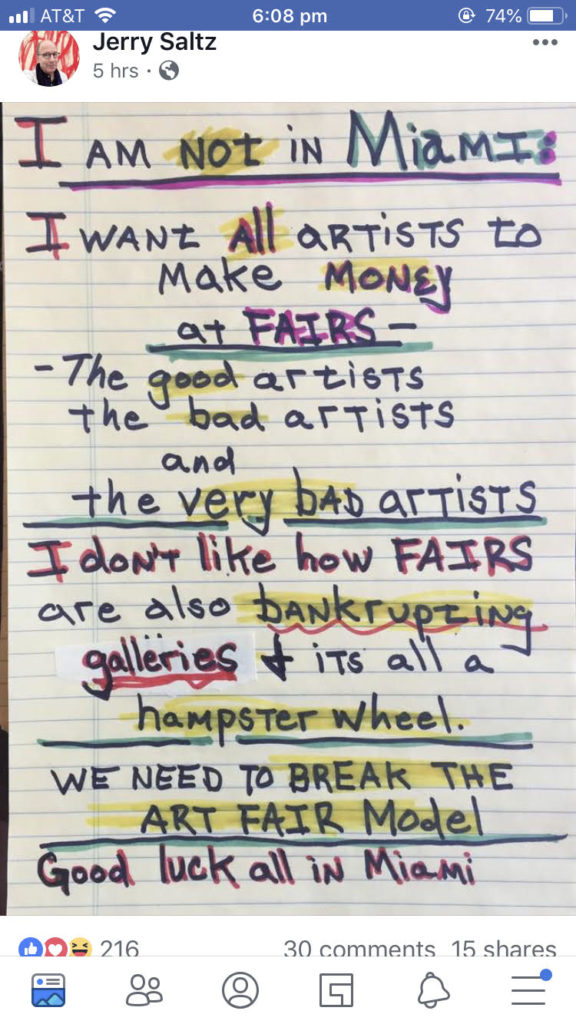

In a fit of histrionics, Jerry Saltz exclaimed: “WE NEED TO BREAK THE ART FAIR MODEL.” That’s like saying cheese is broken—what makes some salivate renders others sick. How do you incite an insurrection against Jarlsberg? (Cheese also happens to contain casein, a chemical that replicates the effects of morphine on the brain—just like art, and some fairs.) I’ll tell you what is wrong with the Basels and their ilk as concisely as I can: Nothing. That they should transmute and evolve goes without saying. I know a talented young artist who was showing for the first time in the fair and was nervous, excited, and enthralled in equal measure—then relieved after she sold out a solo booth in a secondary section of the fair.

I love you Jerry but get over yourself; nothing is perfect or fixed, but it ain’t broken either—far from it. Screengrab courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

One thing I feel compelled to address is what I call feel-bad art; it generally looks awful and is offensive to the eye(s), but that is what’s supposed to make it good for us. It’s also very expensive. This genre of art, largely born in the 1993 Whitney Biennial, was characterized by a fever pitch of political correctness that one critic at the time termed “grievance art”; 25 years later, the malaise had reached epidemic levels. The worst offender is Rirkrit Tiravanija, who I happen to like and admire, but still… his $115,000 painting at my friend Gavin Brown’s enterprise declared: “RICH BASTARDS BEWARE.” It was number one of god knows how many, which says it all. I’d counter that rich artist bastards might also take stock.

Some of Tiravanija’s other transgressions include “SAME NOT EQUAL,” “UP AGAINST THE WALL MOTHER FUCKER,” and “ALL YOU NEED IS DYNAMITE,” which is all well and good unless you are selling these to wealthy people from Palm Beach. Then it smacks of ridiculousness, pretension, or hypocrisy (or all the above). There were shiny metallic ping-pong tables too—he seems to be serving up a game of guilt and gilt. Talk about having your cake and forcing it down the throats of the gullible.

Feel-bad art gone wrong; or, when the original intent of Jeremy Deller’s bittersweet message gets coopted. Screen grab courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Rirkrit was far from acting alone. David Shrigley, who I also like (he shows at Anton Kern, another talented dealer), exhibited a neon: “Large fancy room filled with crap.” So let me understand: Additional crap for large fancy rooms filled with crap? It’s a tautology that is also awful art. Jeremy Deller at the Modern Institute—another interesting artist and gallery—displayed a banner stating “Hello, today you have the day off” that was meant to highlight the plight of freelance employees with no benefits or work assurances… but morphed into a meme machine for disgruntled gallerists. Jack Pierson’s “Rich Kid Blues” served up the same. Please, an environmental plea: Save us from schoolmarmish, didactic art. It’s not preaching to the converted—it’s whining to the culpable who, incidentally, subsidize your first-class, five-star lifestyle. Enough self-affirming liberal backslapping cloaked in pseudo-vitriol.

On another note, it’s nothing short of long overdue that the art world is on the precipice of opening the floodgates of inclusivity, something both crucial and moral, and obviously warranted by nature of sheer talent alone. There are more art opportunities than ever before, but, in the hands of dealers, it’s also an exercise where the market sell-ebrates as much as celebrates overcoming inequality. Face it, there’s little to no pure altruism in the world (especially the art world), but in the end it’s a meritorious marriage of convenience where everyone manages to win for once. Please understand my sincerity and lack of cynicism.

In a 2014 W magazine article entitled “Hot Pot” featuring Essex Street and a few other galleries, proprietor Maxwell Graham said: “I don’t want my artists to rely on art to make a living. I almost wish my younger artists would take after the older ones and disappear for 30 years. And, hopefully, I’ll be here for them to come back to.” The way the young dealer, going on his seventh year, treated me (brusquely), they might just have to. Okay, so he took offense to a collage I made of his gallery featuring a depression-era hobo, the premise of which was that dealers are the new starving artists. He’s actually super-talented and I admire his intransigence, even though he acts like a younger, impecunious version of Matthew Marks.

For all intents and purposes, I got blanked by Maxwell Graham of Essex Street Gallery while admiring the amazing Cameron Rowland works. A Matthew Marks in training. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

My interest was sparked by his artist Cameron Rowland, all of 30 years old and already a Whitney Biennial veteran and in the collection of MoMA. The works were comprised of a series of the slender vinyl signs, all but invisible in the urban landscape, that advertise museum and gallery shows, which at the fair were affixed to the walls of the booth at painting height. These anti-billboard-sized announcements (all from MOCA in Los Angeles), are like gentle prods rather than over-the-head advertisements.

As seductive as they look, the street banners are redolent of a much less appealing phenomenon—they demarcated the neighborhood around the museum in LA where more than 7,000 residents considered “degenerate” by local authorities were kicked out of their homes so the area could be redeveloped. Cameron pulled off a rare balancing act, where he created art sublime enough to function aesthetically and symbolically; it looks good and packs a punch, too, bringing to the fore swept-under-the-rug, debased, and corrupt governmentally sanctioned behavior. They sold out at $30,000 a pop, and, as shallow as I sound (but it’s Miami!), they looked fantastic.

Inigo Philbrick opened a gallery in Miami with an show of Wade Guyton, Avery Singer, and Bridget Riley. The elegant, compact space is conveniently sandwiched between the de la Cruz collection and the ICA Miami in the Design District—brilliant for those who absolutely have to get their buying fix after visiting the nonprofits. Until now, the young dealer (an American living in London) has kept a low profile as a secondary trader well known among the cognoscenti for being shrewd and having a mind of his own, a rarity in the market. His father was a noted East Coast institutional curator, so he had a foundation of knowledge but not a load of dough so he’s informed and hungry.

The back room at the gallery of Inigo Philbrick—a bright light on the horizon of the Miami gallery scene. And I’m not just saying that because he’s showcasing my elephant sculpture. Photo by Kenny Schachter.

In full disclosure, Philbrick—a friend—wrote two essays for a new book I am releasing for my Kantor Gallery exhibit in LA in February, and stocks my self-sucking elephant sculptures in his gallery. With Philbrick’s enviable track record as a buyer, seller, and auction player, that could only bode well for my burgeoning new art career. In the end, I wouldn’t say he’s ruthless, and I certainly do adore him. But you know art dealers—he’s as coldblooded as the best that ever was.

In Kafka’s short story, “A Hunger Artist,” a caged performer became famous for nearly starving to death until interest waned and shifted in favor of a contented, well-fed panther. We have a skewed version in the art market today, where feeders (spec-u-lectors) stuff artists with wealth ’til they explode like Mr. Creosote in Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life (as in the case of the Zombies), or become Damien Hirst.

But here is some breaking news to end the season on: Neither fairs nor galleries nor auctions nor museums are broken. Yes, nothing is perfect, but they manage to hum along just fine, thank you, at an ever-fascinating pace. Yes, changes are afoot. Dealers, from what I hear, are disillusioned with low profit margins, and the sheer volume of fairs is nothing less than profligate; though many profited in Miami, other fairs will suffer. I definitely need a break though—a rest cure in a sanitarium for a few years may do the trick. The upside, if any, of leaving Miami prematurely (I was actually having a good time), was a peaceful, non-art-soaked plane trip home.