Opinion

Wynn Some, Lose Some: Kenny Schachter on the Parade of Art and Depravity at New York’s May Auctions

Following a $3 billion spree of art auctions, artnet News's columnist shares his stories from the sales floors—and it's not (all) pretty.

Following a $3 billion spree of art auctions, artnet News's columnist shares his stories from the sales floors—and it's not (all) pretty.

Kenny Schachter

The latest spate of New York auctions that transpired over the past two weeks saw nearly $3 billion worth of art trading hands, a mind-boggling sum. But beware: Springtime in Manhattan is a season characterized by falsehoods and subterfuge, not so much by the regulated auction houses (them too, of course) as by the lunatics running amok in the salesrooms.

If cocaine and caviar were cheap from the get-go, I doubt there’d be much demand for either—which is not to say that the hunger for art is solely generated by Veblen tendencies, but ever-escalating sums fuel greed and concomitant bad behavior. Part of the value of art is the ever-rising value of art. It’s an upward-spiraling, self-fulfilling prophesy of worldwide interest and participation. (Witness the conspicuous-consumption veneration of the barely there da Vinci.)

On the auction front, there are tales of experts not requesting but rather demanding kickbacks for offering advice on deals and guarantees; consignors bidding up their own works (not always successfully); and creative lighting effects employing filters that would make Spielberg blush. (Me: “Wow, look at the popping purple in that Mark Bradford!” Specialist who knows better: “Wow, look at the clever lighting!”) During my stay in New York, I saw a convict being led for a stroll down Fifth Avenue shackled to an officer in handcuffs; I wouldn’t be surprised to catch such a manacled bidder raising a paddle at auction one day.

Dealers are worse—and I have personally experienced all their bad behavior —with partners misrepresenting sales outcomes to each other, and concocted SWIFT codes evidencing transfers that were never transferred. (In which instances, “swift” is the mother of misnomers—the new “check is in the mail.”) I asked another why he looked me in the eye and continued to lie (and lie), and he replied: “I like to tell people what they want to hear.” Then we had dinner. Ugh. Yes, there’s no denying the barefaced turpitude of an auction cycle, but it was (very) far from all bad.

Sotheby’s doles out freely flowing booze to live musical accompaniment before their Imp-Mod sales—which might account for why they’ve been nipping at the heels of their contemporary competition. “I’ll have another drink, and make that two Modiglianis—or was it the other way around?” I remember a time when $275 million, all in, wasn’t considered a disappointment for a couple paintings, as was the sentiment expressed after the sale of the Modigliani Nu couché and the Rockefeller Blue Period Picasso at Christie’s—both of them guaranteed and bought by the Nahmad clan. You heard it here first.

The Picasso was supposed to elicit Chinese bidding (it didn’t), and word on the street was that “some people had a problem with the feet” on Modigliani’s nude. Um, okay. The garbled, heavily accented speech of the stiff auctioneer, which an auction-goer compared to a character in the Rocky Horror Picture Show, certainly didn’t help. Or was it the crying baby on the sales floor that put people off? I thought I was bad taking my kids to… everything. I think what freaks people out is when a supposedly un-choreographed auction turns into a prearranged marriage via an endless stream of guarantees. And the air is thin at that altitude, though perfectly pleasant for the likes of Yusaku Maezawa, who dropped $18,856,500 on a Rothko work on paper (no less) against an estimate of $7 million to $10 million.

Time to spice up the auctions with a little Frank-N-Furter—can’t be worse than what they have already. Photo illustration by Kenny Schachter.

I met young Max Moore, all of 25, who went from compiling catalogues in the basement of Sotheby’s a few years ago to heading up day sales at the auction house after a series of defections and firings. He’s bright, talented, and on the rise, though he was clicking his pen top with such ferocity during our convo I almost strangled him. His brain-surgeon dad Frank helped throw my stag party at Scores more than 22 years ago (don’t blame me, I was just the stag-ee) before he became the mega-collector he is today. And, are you ready for another breaking-news bombshell? Could Larry G. have laid a surprising succession plan under our collective noses?

I have heard from half a dozen market denizens that Gagosian, who recently celebrated his 73rd birthday (happy, happy) has struck a deal with Moore Sr. to take a leading role in the enterprise. I texted Larry on the topic, who shot me down with a succinct “No!” before I could press send, and Frank similarly denied all. But then again, Trump said he didn’t know about the Stormy payment. They say art dealing isn’t rocket science, but when it comes to replacing the charismatic and, yes, brilliant Larry G., no less than a brain surgeon will do. Let’s see….

Jerry, Jerry, Jerry… when will you learn, if ever? Screengrab courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Jerry Saltz (sorry, can’t help myself) called the Rockefeller sale the “whitest room in Christendom” on Instagram but failed to take note that, at nearly $1 billion, it was also the largest charitable auction in history. At least as significant was the slate of works in an integrated component of Sotheby’s contemporary evening and day sales entitled “Creating Space: Artists for the Studio Museum in Harlem,” curated by longtime director Thelma Golden to raise money for a new building. Golden has been affiliated with the Studio Museum on and off since 1987, with a 10-year stint at the Whitney Museum from 1988 to 1998. With the roaring, unprecedented success of her sales, which smashed expectations, I bet Thelma awoke to more than a few beckoning messages from Larry G.

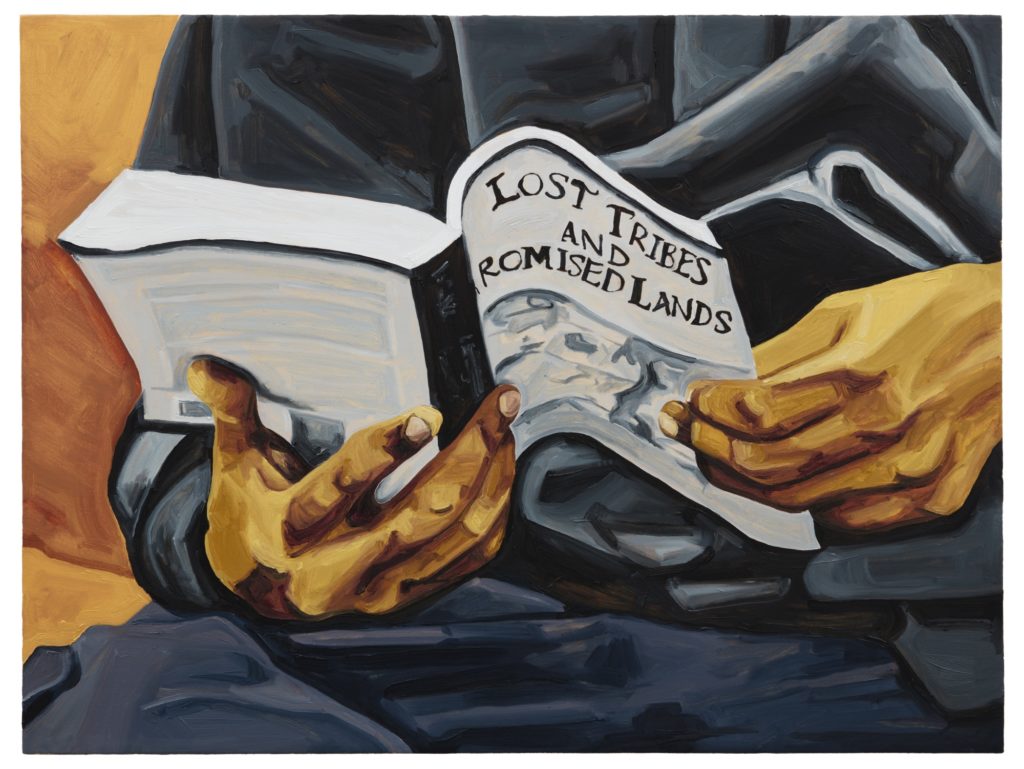

Reviewing Gavin Brown’s amazing Arthur Jafa exhibition in the New York Times, Roberta Smith (Jerry’s genius wife) captured the fomenting societal transformation afoot, calling the show “an uplifting slap in the face of white America.” The same could be said for the Studio Museum’s contingent of works that sailed over high estimates, not to mention the Kerry James Marshall that didn’t just break the glass ceiling of prejudicial art pricing but obliterated it. When I blurted to my seatmate how great the $21,114,500 Marshall result was (which wasn’t part of the Studio Museum sale), he replied without missing a beat: “Great for the seller.” Nevertheless, I was glad to be in the room to witness the seismic shift.

Jordan Casteel: you could learn something new from Thelma Golden’s Studio Museum in Harlem sale at Sotheby’s. Image courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

The gross estimates of the eight Kerry James Marshalls for sale at the combined houses throughout the course of the week was $15,880,000 to $39,650,000, and the result? An unabashedly whopping $33,336,500. Wow. Among the strongest performers in golden Golden’s section of the day sale were three newcomers who oddly all made the same result of $81,250: Titus Kaphar, who has had seven pieces at auction to date, against a $10,000-$15,000 estimate; Jordan Casteel, her first piece ever at auction, estimated at $15,000-$20,000; and Derrick Adams, also first auction appearance, on an estimate of $20,000-$30,000. All told, this accounted for a transition into a more democratic art world, and we are the better for it.

Nice to see my Instagram friend Derrick Adams go through the roof in Thelma Golden’s Studio Museum in Harlem benefit sale at Sotheby’s. Image courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Fernando “I-do-not-paint-fat-people” Botero, who claims it’s volume and sensuality of form he’s after, was once asked in an interview if he was obsessed with the zaftig. He replied: “No, no, not at all. I have been attached to three women, all of them skinny.” Of eight works for sale this cycle, all found buyers above the low estimate, while a trio exceeded the high—and a work at Sotheby’s did so by a factor of three. Between now and the first week of June, there are yet another 19 of his works at auction from Stockholm to Hong Kong. Kate Moss said nothing tastes as good as skinny feels, and, though Giacometti is a market darling, being portly pays. In art, anyway.

Not fat, just big-boned. Photo illustration by Kenny Schachter.

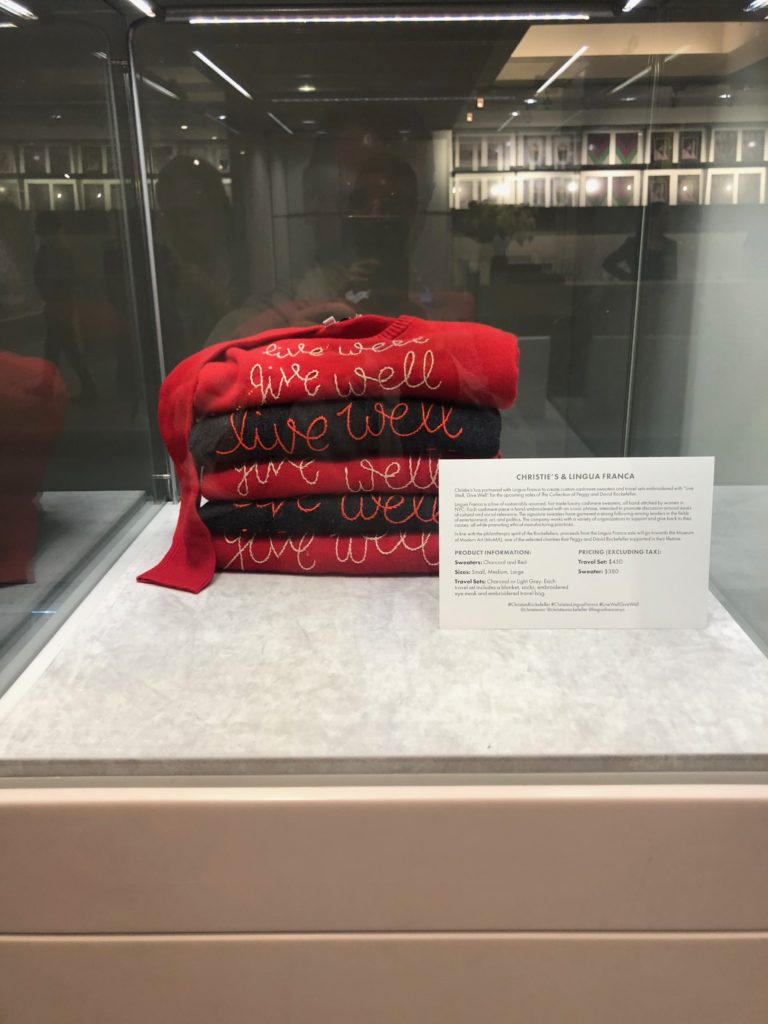

I brought my visiting 82-year-old father, who I haven’t always gotten along with (and who’s fitter than me), to the presale viewing at Christie’s thinking he’d relate more to the souvenir merch for sale in the lobby than the silkscreened erasure paintings of Christopher Wool. I was hoping for some gratuitous criticism of the variety I was endlessly exposed to (kidding, dad) so I could report it, but instead encountered an unbridled sense of wonderment, even for Koons’s $20 million pile of Play-Doh, sold by Greek Cypriot Dakis Joannou and guaranteed by the same player as the Robert Gober, which broke a record at $7,287,500. Art as healing salve, bridging relationship divides in real time: who’d of thought?

Christie’s merch. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

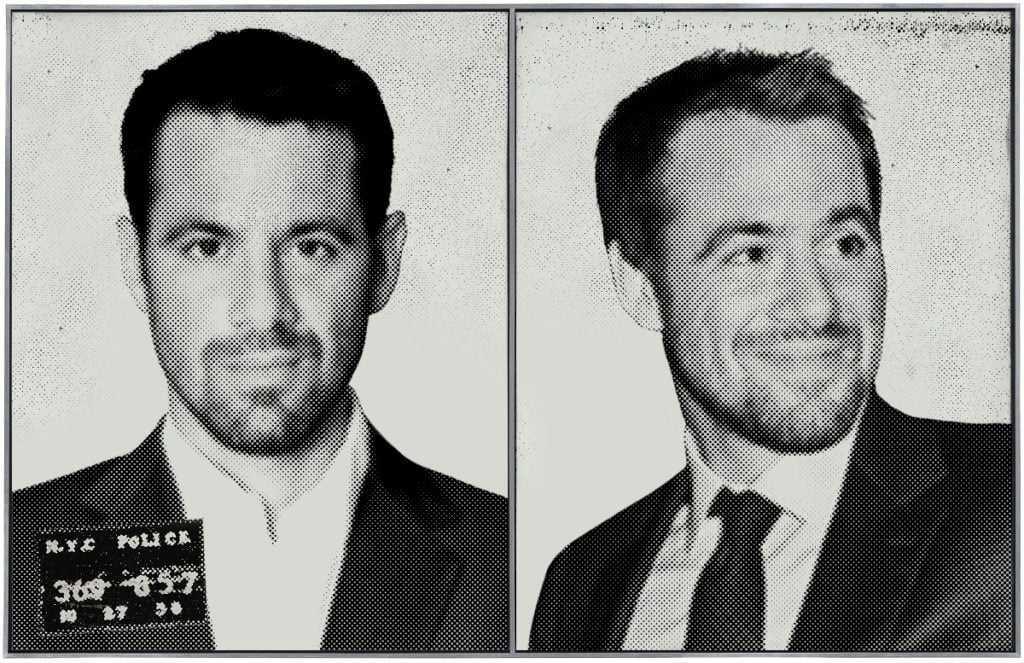

Wahol’s Elvis came with an estimate of $30 million and sold for $37 million (with fees), exactly matching the estimate and sales price from 2012 when the Mugrabis purchased and promptly flipped the work. The subsequent purchaser, at a price said to be at or near $60 million, was Steve Wynn, since #MeToo-ed out of his casino empire. Wynn recently announced a new venture in the art trade, following a tack taken by another fallen art luminary, Cy Twombly estate lawyer Ralph E. Lerner, who became a dealer following his suspension from practice. Note to Wynn: It’s best he bone up on art handling after the second major mishap to befall a Picasso under his care—not the most auspicious start to a blue-chip dealership.

if you should encounter this man, beware, he’s armed and dangerous (with auction-house guarantees). Photo illustration courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

An aside: Bob Dylan was gifted another iteration of Warhol’s Elvis by the artist, which Dylan carted home on the roof of his station wagon, then used as a dartboard before trading it to his manager for a couch. Dylan was famously dismissive of the artist, at his own expense. Another major Warhol work (that sold for $28 million, under expectations) from his “Most Wanted” series bore a striking resemblance to Christie’s mercenary, spearfishing Chairman for the Post-War & Contemporary Art Department, Loïc Gouzer. I’ll assume it was mere coincidence, rather than presaging anything.

Going, going… hello, it’s back! A Donald Judd makes a reappearance at Christie’s day sale. Image courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

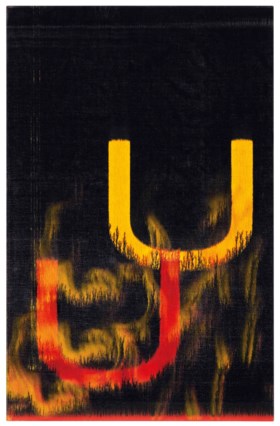

When is a pass at auction not a no, but a go? In the case of a Donald Judd, unsold in the morning sale but re-offered in the afternoon after a lower price was agreed to by the consignor and a would-be buyer, who wanted to have the work recorded as sold rather than bought in. When bidding reached that pre-agreed price, however, another unknowing paddle sprang up—outbidding my pal and blowing his clandestine ploy. A Wade Guyton, from his most coveted series of “Flaming U” computer-printed paintings, sold low at $1 million (the record is $6 million) due to the fact a conservation report was circulating indicating the work was in poor condition. I know of other similar such issues, not just at Christie’s. This is when art auctions resemble used-car sales: caveat emptor!

Buyer beware: a damaged Guyton on the block (with a clean condition report) at Christie’s. Image courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

What’s at five in the afternoon besides the matinée of The Lion King? Why, that would be Phillips evening sale of 20th Century and Contemporary Art. There was a series of micro Warhol flowers, assembled by fabled dealer Ileana Sonnabend and being sold by—you guessed it—the Mugrabis, who guaranteed Warhol’s Last Supper. This is when art resembles high-stakes horse-trading.

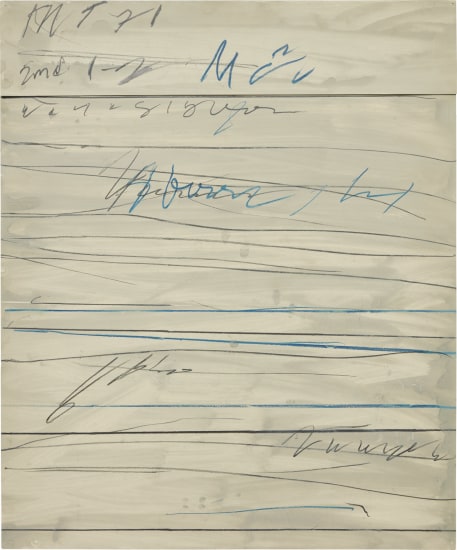

A few years ago, advisor Todd Levin of the Levin Art Group—which I gather is Todd and his assistant—lashed out in a thread on my Facebook page, but rather than attack my (probably untenable) art argument, he chimed in with a dig at my in-laws. Sometimes the art world resembles the schoolyard. Todd was bidding on a Twombly work on paper as I related the story of his unprovoked meanness to the friend I was seated next to. Levin manically flicked his wrist to indicate each successive bid with such fervor that my friend determined he’d go higher—and, in a move of unheralded solidarity, threw up a bid of $100,000 higher, which Levin topped. In other words, Levin’s Facebook transgression cost him $200,000 more than he would have otherwise had to pay for the work, which cost him $1,455,000 on an estimate of $800,000 to $1.2 million.

Bully me at your own expense, Todd. Image courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

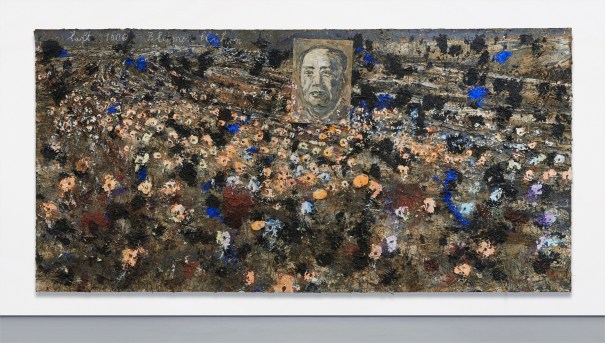

An auction expert at another house (she’s never wrong) related that Canadian collector/dealer François Odermatt (who has a few sexual-misconduct allegations of his own to contend with) sold an Anselm Kiefer and Mark Grotjahn with no reserve—and, in return for the gamble, got back a portion of the buyer’s premium. It still didn’t go exactly according to plan when both works sold at or near their low estimates. The Kiefer featured a depiction of Mao, a tough sell these days. (I should know, I have a Warhol version if you’re interested.)

No one appreciates the Chairman anymore; Kiefer’s Mao at Phillips. Image courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Art advisor Kimberly Chang did better than her client Guy Laliberté when she sold her Kerry James Marshall for $4.3 million, but she turned down a higher guarantee before. Laliberté’s Polke passed with the $12 million estimate. (The house desperately sought a guarantee before the proceedings to no avail.) Phillips lost on a major-sized Richter abstraction as well, which also passed. The German works were included in a section entitled “polke/richter richter/polke,” the name of a famed 1964 exhibit that the artists jointly held in Hannover, and which also happened to be the name of the show I curated in 2014 at Christie’s private-treaty gallery in London. Ha, serves them right.

Phillips stages tight little sales that are what they are. I’m not judging them other than to say they will always be niche, and it’s a crapshoot at that. I’ve seen just about every contemporary sale they’ve ever conducted, and, safe to say, my feelings haven’t altered: unless the work would sell itself, or there’s no alternative, I’d sell at Christie’s or Sotheby’s and buy at Phillips, because in most cases you will pay less or receive less, depending which end you are on. Rudolf Stingel’s Untitled pair of fighting birds, previously in the “collection” of Leonardo DiCaprio, sold on an in-house guarantee for about $6 million. Phillips must have a hell of an art collection. P.S.: I heard Stingel bought a private plane.

Lost an arm, leg, or shirt in New York? No, just a sneaker this time. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

University graduation season helped hike hotel rates in the city (any excuse will do), and the art market also graduated to a greater state of equity between races and genders. There is so much art I can fall in love with, even at Phillips, that I let myself off easy by not buying anything (if I did at this stage, I’d need terms… for life). When I arrived back in London, there was a lone sneaker circulating on the baggage conveyor belt. Though I didn’t lose an arm or leg, I was lucky to get out with my shirt on. Don’t get me wrong, even without art-world Viagra (crime and guarantees) the art market would be as firm as Tom Wesselmann’s forever-erect penis (sold at Christies for $93,750, est. $40,000-$60,000), and it won’t subside anytime soon.