Opinion

Has the Art Market Reached a Stage of End-Game Nihilism? Kenny Schachter on New York’s $2 Billion Auctions

Our columnist explores the underbelly of the six-day feeding frenzy of Impressionist, Modern, and contemporary auctions in New York.

Our columnist explores the underbelly of the six-day feeding frenzy of Impressionist, Modern, and contemporary auctions in New York.

Kenny Schachter

Last week, in just six days of Impressionist, Modern, and contemporary auctions in New York, around two billion dollars of art was sold—with even more sales taking place afterwards, as a slew of the bought-in lots will inevitably find new homes (or freeports). Where does it all go, wave after wave of artworks? It’s nothing short of miraculous how much art gets swallowed, in a global feeding cycle that (for now, at least) seems set on endless repeat. The total amount of work at auction across Phillips, Christie’s, and Sotheby’s this round came to 1776 lots—fittingly enough for America’s starriest sales sequence—with Impressionist and Modern accounting for 742, and contemporary for 1,034.

The contemporary results at Sotheby’s and Christie’s were nearly identical, around $462 million and $452 million, respectively. I’d say the performance metrics of the two houses are fungible—six of one, a half-dozen the other. As long as the other isn’t Phillips.

Hogarth tried to subvert the auction houses and galleries with a single artist auction of his very own, way back in the mid 1700s. What’s really ever new in the art world? Image courtesy of Kenny Schachter..

William Hogarth’s The Battle of the Pictures originally appeared printed on the bidding tickets for his single-artist sale in 1743 (there’s nothing new under the sun, Damien), where the social satirist—best known for his paintings cycle “A Rake’s Progress”—flogged his own canvases to bypass the entrenched auction houses and other intermediaries. The image on the tickets depicted Old Master paintings escaping from an auction house, physically attacking Hogarth’s artworks as they emerged from his studio. Increasingly, it’s contemporary art that clobbers every other category of art for sale—a trend that won’t change. Until whatever comes next, that is.

Having lived nearly 15 years in London, I could write a book on the cultural, political, and linguistic dissimilarities between the UK and the United States, but one observation I can’t shake is how much thinner American toilet paper is. Surely, this is due to two factors: it’s cheaper and necessitates more enthusiastic usage. Sort of like money—the lower the cost (minimal interest rates) and the easier to get your hands on it (including ready art finance), the bigger urge to deploy it.

Access to money doesn’t equate to connoisseurship—far from it. Generally, greater sums chase a limited (but not necessary better) universe of stuff. I’m being generous, but every year or so new artists make their way into the market (for various reasons) and serve to broaden the breadth of the received canon, which lately has led to closer parity in prices achieved by artists across races and genders.

This brings me to guarantees and their impact on the changing role of auctions in today’s burgeoning art market. Guarantees started in-house in the 1970s and expanded to third parties in 1999 when Sotheby’s found a backer for a $40 million Picasso. Since then, snowballing guarantees have had a dulling effect on bidding, but serve to anchor the market—contributing to stability, if not confidence.

As a direct result, the market has grown over the last 20 years to resemble an ATM machine for spec-u-lecting traders. This new breed of “collectors” are not selling to prune their holdings, Bonsai-style, as in days of yore, and their acquisitions are rarely motivated by any impulse other than to generate buy-sell activity. Why? Because for the first time (to this extent, at least), they can.

Unlike Jerry Saltz, I don’t rabidly begrudge the spiraling art market; it just is, and I accept that there’s positive spillover too, expanding the audience for whatever reasons. This may not be Jerry’s art world—or the cozy, high-minded sphere that many others signed up for, for that matter—but the playing field is spread out enough globally (something to be thankful for, despite political blathering to the contrary) that there are entry points for anyone interested to partake at whatever level. Guarantees liquefy art for an audience that demands straightforward and relatively easy exit strategies, versus relying on the selling abilities of cash-strapped art dealers.

The latest evolution (if you can call it that) of this questionable financial instrument is that houses are selling guarantees like slices of pizza, in what smacks of a largely unregulated derivative market. Further afield, or on another planet altogether, Nasdaq just released that the Chinese company Yulong Eco-Materials Limited is offering fractional ownership of a $75 million Michelangelo Crucifixion via listed shares (Nasdaq: YECO). Most amazingly, it’s financed by the shareholders themselves, through the issuance of shares that surged nearly 50 percent upon the announcement.

They have 30 days to generate enough money to buy the painting to close the deal… let’s see what happens. Sounds like something I need: a self-funding collection. Welcome to the age of art as another sector of the financial services industry.

Wildlife photography, art-market style (and equally as dangerous). Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Forget fake news—the art world recoils from the truth. (After a handful of death threats and flying fisticuffs sparked by my columns, I can readily attest to that fact.) Throwing caution to the wind (again), here we go: John Sayegh-Belchatowski, a canny and enthusiastic investor, guaranteed four Basquiats at Sotheby’s. How do I know? As many people told me as heard him extolling the virtues of the pieces to any and all. (A request for comment went unanswered at time of publication.) Though the gamble came up short (this time) regarding the most expensive of the group, the Warhol/Basquiat collaboration beat its $9 million high estimate to total $9,443,900, disproving the market maxim that, when it comes to collaborations, one plus one (or two) typically equals zero.

Another painting at Christie’s, jointly owned by two of the biggest Basquiateers (one affiliated with a major gallery, one not), was guaranteed by another ubiquitous member of the club, all of whom own similar text-based works and play in the same sandpit. In the process, the painting seemed to go to the guarantor—manufacturing a nice market notch for that variety of work. (Collecting Basquiat is practically a full-time job these days, and a multibillion-dollar business.)

Word on the street is that Lévy Gorvy Gallery was taking big punts at Christie’s on lots that may have included the Pollock and the de Kooning. I suspect they were bidding on behalf of none other than Christie’s owner François Pinault (Brett Gorvy’s former employer), and not faring particularly well. (The de Kooning went to the guarantor, I hear, while the Pollock got away.) If true, chalk it up to a personal loss that translates to a win for the house—and since Pinault controls the candy shop outright, kit and caboodle, he appears to care about brand value more than profit and loss. In fact, that seems to have been the case for years. He’s certainly got the motive to window-dress the company for a future sale down the road.

Back at Sotheby’s, a 1987 Gerhard Richter abstract came under the hammer that had been purchased by a French collector for some 95,000 francs shortly after it was made. My understanding is that, at $30 million, it went on the guarantee to Hauser & Wirth. Richter famously has asked for lower prices on his works and that’s what he got—the record for a squeegee work stands at $46,352,960 in 2015. Many were expecting more for this double-paneled work, as perverse as that sounds.

Longtime California collectors Norman and Norah Stone decided to sell two great early Christopher Wool paintings that they’ve owned for ages, and contacted the artist’s gallery, Luhring Augustine, citing personal reasons for offloading the works. When the gallery clocked that the couple was simultaneously shopping guarantees, I’m told, they were less than amused. Luhring and Augustine got extra pissed, incandescent even, when they caught wind that the famously disdainful-of-the-market Wool agreed to a dinner with Sotheby’s and W magazine—the lifestyle magazine for what art has become—to celebrate the occasion (of money changing hands?). In no uncertain terms, Luhring Augustine RSVP’d via their lawyer, making it clear they wouldn’t be attending, nor would Christopher. And that was the end of that.

Going, going, gone; please make dinner plans elsewhere. I wasn’t invited anyway. Screengrab courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Guarantees are not always guaranteed! I hear one private dealer had an agreement on another Wool painting at Phillips but managed to stall the signing of the contract until she rocked up at the house the night of the auction (if you can call the early hour they conduct evening sales, timed to occur before Christie’s, “night”) at which time… she changed her mind. Oh well, the house had earlier turned down a substantial offer just below the $4 million low reserve. The consignor had held out for more, and ended with nothing. Greed is not necessarily good (if ever).

Phillips has repeatedly and in no uncertain terms complained of the tenor of my coverage over the years, though they could never disprove my veracity. Ever. So, to avoid even the appearance of negativity regarding their overall performance, the rest is best unsaid.

The downside of going naked (sans guarantees) is that success affirms success, and great quality alone is no guarantee that an artwork will prosper—and sometimes even precludes it. Being too far ahead of the times, it so happens, can be as detrimental as being behind. Ask Mitch Rales, who with his wife Emily own the Glenstone private museum in Maryland (I’ll save my views on private museums for another occasion). Together they tried to sell a monumental Sigmar Polke painting at Christie’s, but withdrew it after no interest materialized. He may have additionally owned the equally fantastic Bruce Nauman neon Run From Fear, Fun From Rear (also at Christie’s) that passed unsold. They were the two works I most coveted from the series of auctions (and equally couldn’t afford).

When it comes to high-profile un-guaranteed consignments, the houses aren’t shy about throwing in not just a vigorish but the whole kitchen sink in addition to a fee. I don’t care to speculate on the whereabouts of Hockney’s swimming pool—I’m not the art world’s Oliver Stone (though there’s an opening if there ever was one)—but there are reasons to bid up your own work, especially when it pays off, literally. For starters, you can gear up (borrow) against a fat higher valuation. Then there’s the fame and notoriety you gain. (You may have noticed the Hockney on the internet—you’d have to be catatonic to have missed it.) It can even be a form of bequeathing, between family members or offshore entities (our new kinfolk).

The affair smelled rehearsed, preordained, a priori, and otherwise orchestrated. Even the rapport between the auctioneers seemed scripted and too relaxed on such a big lot. Really? If Joe Lewis bought back his own painting, and I’m not saying he did, Christie’s might not mind—it would contribute to increasing the house’s revenue on the books.

When the markets play in art they often get it wrong—very wrong. I should fail so well. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

There are two collectors whose names sound veritably the same but hail from Mexico and Greece who happened to be involved in a Warhol mega-deal together, by way of a Swiss dealer who represented the Greek on the sale of the blue “Disaster” painting well in excess of $100 million. If that constitutes a softened market for the master, god bless him. The Greek in turn splurged on the Pollock (buying it on one bid) and Calder at Christie’s. This is the merry-go-round that makes the art market the hotbed it is today, a pit no less frenetic than the NYMEX (New York Mercantile Exchange)—and with similar levels of risk.

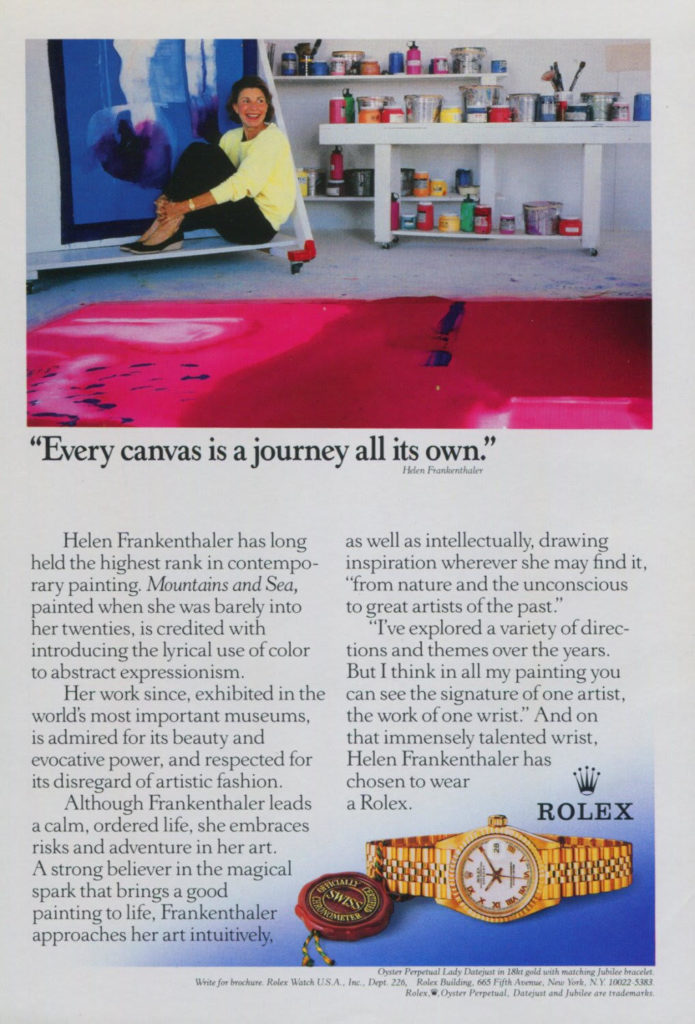

Helen, it can’t be so… Joan Mitchell was incensed apparently. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

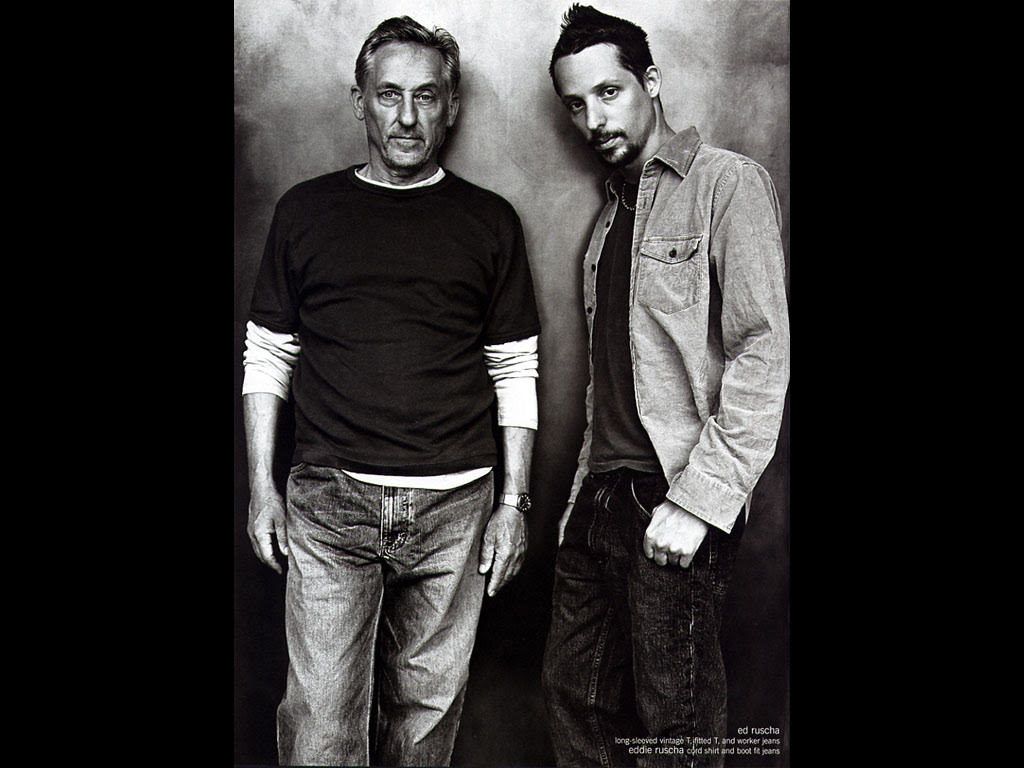

I couldn’t enter my hotel without encountering an entire building overrun with KAWS decals of bastardized “Sesame Street” characters like an nasty outbreak of chickenpox. On another note, researching artist endorsements, I came across examples by no less than Helen Frankenthaler from 1994, in which she seems to be saying that the artist’s hand is all in the wrist, especially when its sporting a Rolex. Flash forward to 2002, and there was Ed and Eddie Ruscha, the steely LA painter and his son, shilling for the GAP, striking poses worthy of any scene in Zoolander.

So, with Koons and his bags, Murakami and Hirst with their everything, the spiritual content of art is veering to the calibre of profundity of the local brand of toilet paper. Call it Conceptual Art Light (on concept). With KAWS, maybe my disdain stems from the fact that I was too close to Big Bird as a kid to find the humor or artistry beyond Jim Henson’s initial genius, especially when my large avian childhood friend is presented to me with the X’d-out eyes of a cartoon cadaver. Call me cynical, but when dealer Per Skarstedt goes to the dark side by representing this perfectly fine commercial artist, we are left scratching our collective heads, and suffering a little. But the money continues to pour in with the record-breaking sales I can regretfully report.

Ed and Eddie, smoking! Their art’s not bad either. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Since Warhol’s Brillo Box, the products have taken over the art that once took over the products. And then they just became the same thing. Maybe a backlash will soon be underway—I can only hope. My sources tell me David Zwirner cancelled Jeff Koons’s next exhibit due to not wanting to shoulder the (overly) excessive production costs and concomitant lack of demand.

Next up? Art Basel Miami Beach, and I can’t wait (it’s freezing and raining today). Then Los Angeles, where I will actually participate in the Felix Fair, the alternative to Frieze, and have a one-person show at Niels Kantor Gallery. And then, I’m working on an art-market musical! Why not? In art, the meanings of content—as in subject and satisfaction—merge.