Every Monday morning, artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, more proof that the only thing separating offline and online conflicts is a screen…

KICKSTARTING AND SCREAMING

Last Saturday, Nathan J. Robinson, editor-in-chief of the bimonthly progressive political magazine Current Affairs, wrote a searing firsthand account of what happens when an institution has partnered with a digital platform, only to find out that that platform may not align with its values. Current Affairs was in the midst of a Kickstarter campaign when Robinson and his team learned of Kickstarter management’s reported opposition to the staff’s efforts to form the tech sector’s first white-collar union. That turbulence ended with Current Affairs deciding it could no longer work with Kickstarter because of what Robinson deemed (in an email exchange with Kickstarter’s senior director of communications) the company’s “damaging and indefensible position” on the unionization effort.

And while the saga has only thin direct connections to the art world so far, I suspect it could open an online theater in the largely offline war over ethical patronage that has consumed several museums (and much of the art-media cycle) in 2019.

First, the context: Before Robinson and his team concluded that their principles left them no choice but to abandon Kickstarter, Current Affairs and two like-minded publications published a statement that expressed solidarity with the startup’s labor force and blasted the company for its alleged union-busting tactics, including the firing of two staff members heavily involved in the organizing process. (Kickstarter contends that the dismissals were unrelated to their unionization efforts and that it will present evidence documenting their performance problems to the National Labor Relations Board, where both employees filed complaints regarding their terminations.)

The magazine also set up an online submission form for anyone else interested in pledging their support for Kickstarter workers, and Robinson has been posting pro-labor testimonials from other Kickstarter project creators on his Twitter account for days. By the time he published his essay on September 28, vocal allies included artist Molly Crabapple, best-selling author Neil Gaiman, and Anita Sarkeesian, the media critic behind the Feminist Frequency video platform.

Artist and activist Molly Crabapple, one of the Kickstarter projector creators who has come out in support of a Kickstarter union, is arrested during a protest of Amazon’s affiliation with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in August 2019. Photo courtesy @mollycrabapple via Twitter.

A few days after Robinson’s post went live, Kickstarter took to Twitter to proclaim that it “will recognize a union if [its] staff votes for one,” but only if they do so in an anonymous election certified by the National Labor Relations Board. The startup also released a statement from CEO Aziz Hasan and updated an online FAQ about the situation. All of these transmissions are shot through with explicit and implicit messaging that the pro-union segment of Kickstarter’s staff A) isn’t as big as the media would have you believe, B) is unfairly and unduly pressuring undecided colleagues, and C) doesn’t understand how good they have it at the company already.

In short, the two sides aren’t exactly racing toward common ground, and this clash will probably get worse before it gets better.

Now, I’m not going to pretend that I have a comprehensive understanding of every twist and turn in the unionization saga at Kickstarter. But my natural inclination is always to side with workers over management, and nothing I’ve binge-read about the situation this weekend gives me a good reason to deviate from that position. To paraphrase Jeff “the Dude” Lebowski, that’s just, like, my opinion, man.

But the point of this column is not to try to get to the bottom of what is, or isn’t, the truth of Kickstarter United’s struggle for recognition. The point is to show that artists attempting to build their careers through online patronage platforms are now being faced with some of the same ethical dilemmas as artists attempting to build their careers through traditional patronage platforms—and to consider what that means for the future.

Protesters at the Whitney Museum. Courtesy of Decolonize This Place.

IMMORAL EQUIVALENCY

The months-long campaign by Decolonize This Place and other activist groups to oust now-former Whitney Museum trustee Warren Kanders is almost inarguably the highest-visibility and highest-stakes conflict we’ll see in the art establishment this year. As my colleague Ben Davis wrote in the immediate aftermath of Kanders’s paradigm-shifting resignation from the museum’s board this summer, “The Tear Gas Biennial,” a virtuosic essay by Hannah Black, Tobi Haslett, and Ciarán Finlayson published online at Artforum, proved to be the final turning point in the struggle—not just because it renewed a call for artists participating in the Whitney Biennial to withdraw their works from the show, but because it seemed to convince eight of those artists to actually listen.

What made “The Tear Gas Biennial” so effective? Davis contends that it managed to drill through the wall of sound regarding the need for more systemic institutional change and articulate a clearly defined, achievable response in the moment. As the authors write, “If we believe that our capacity to act against this evil”—meaning the powerful influence of dirty money in the art world—“is limited, we should take every opportunity given to us to act.”

In other words: Yes, the problem is bigger than this one specific trustee’s business and politics. But this specific trustee is a part of that bigger problem, and he is close enough to you, WhiBi artists, to actually make an impact. All you need to do is claw back your work from this specific exhibition, and you will strike a blow that radiates upward and outward. Conversely, to leave your work on view in this tainted platform is to tacitly support the ethically bankrupt business and politics that make it possible.

You don’t need otherworldly aim to fire a harpoon from the animus that brought down Kanders to the animus that triggered Current Affairs’ departure from Kickstarter. So how far off can we be from politically progressive visual artists and art organizations feeling like they have to jettison their own Kickstarter campaigns to be able to navigate to the right side of the ethical line?

Well, it turns out we’re already there.

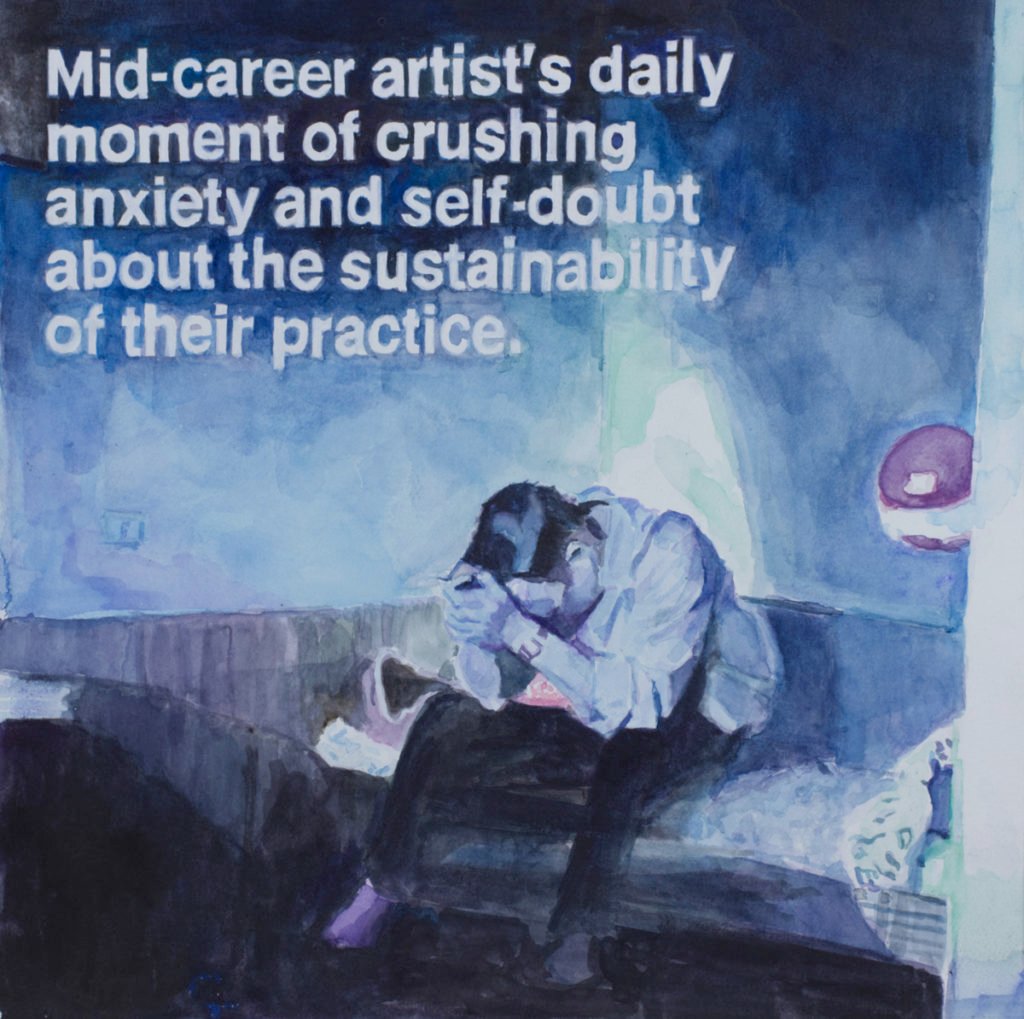

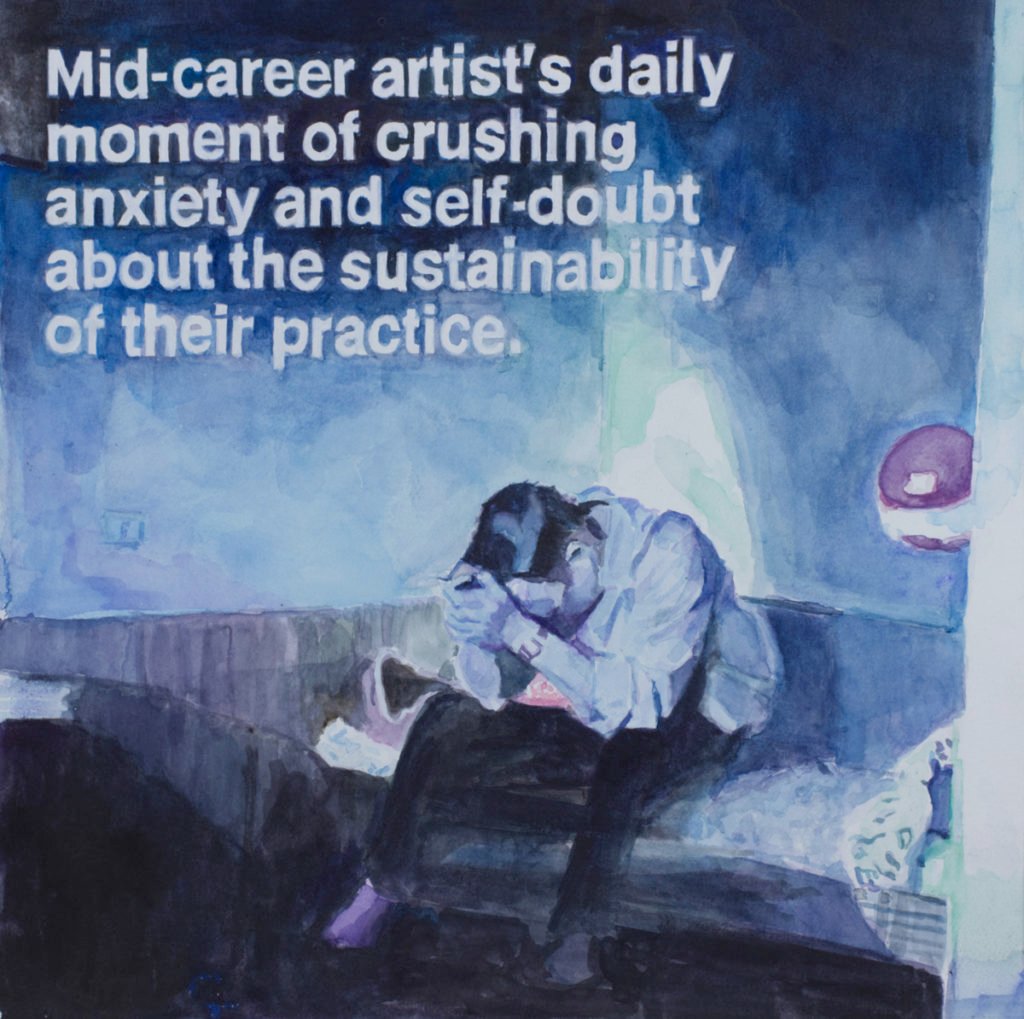

William Powhida, Crushing Anxiety (Chernobyl) (2019). Courtesy of the artist and Postmasters.

NOWHERE TO RUN?

True, you’d be hard-pressed to find many people willing to argue in good faith that the types of union-busting tactics that Kickstarter’s leadership is being accused of are as morally reprehensible as tear-gassing unarmed children at the border or, in the case of allegations against the scandal-plagued Sackler family, profiting off of thousands of lives destroyed by opioid addiction. Also true: the momentum toward organizing among staff at major arts institutions—most recently the New Museum, whose freshly formed union just finalized a contract with management last Wednesday—has not yet compelled artists to pull their work, or publicly reject an exhibition opportunity, over perceived anti-union activity. (Prominent artists such as Tauba Auerbach, Nayland Blake, Andrea Fraser, and, not coincidentally, Hannah Black did sign a letter of support for the New Museum union in January, but that’s obviously a lower-key contribution than a boycott.)

That said, Robinson states that Current Affairs patrons on Kickstarter “began revolting” after they caught wind of the labor battle at Kickstarter, and that he had to try to “convince them not to pull donations” because they couldn’t stomach five percent of their funding being siphoned off by the union-resistant company acting as an intermediary. Also important for our purposes: some of the same artists who took part in actions against Kanders are now pivoting some of their focus to Kickstarter. In addition to Molly Crabapple, artist William Powhida told me in a text message this weekend that he “won’t support anything on Kickstarter again if they continue to maintain their anti-union stance.”

I’m not concerned about the heavy hitters who have benefited from projects launched on the crowdfunding platform if support for a boycott does gain more traction in the art world. I’m confident that Robert Irwin, Ugo Rondinone, and Olafur Eliasson, among others, are going to be just fine with or without Kickstarter.

But what about the hundreds, if not thousands, of lesser-known artists, many of whom began working with Kickstarter precisely because they have not managed to get traction in museums, galleries, or other players in the legacy art world? If they feel pressured to abandon arguably the most prominent online-patronage platform around, how do they replace the lost revenue? (Patreon, Kickstarter’s most direct competitor for crowdfunding creatives, has faced its own scandals over increased fees and alleged political bias, albeit from the opposite side of the aisle.)

To be clear, I am not—repeat, not—saying inclined artists and art professionals should think twice about boycotting Kickstarter because of the temporary pain it could cause to project creators. That would be the same kind of scare tactic that anti-union executives have spouted for decades to try to maintain a pro-management status quo. Meaningful change almost always requires meaningful sacrifice.

Still, the consequences are real, and the solutions uncertain. Regardless of your personal stance, it seems clear that the online-patronage ecosystem is becoming as tumultuous as the offline one for which it was supposed to be a healthy, inclusive alternative. It just goes to show, once again, that the internet is not necessarily an escape from IRL challenges. Often, it’s just a new arena for us to fight the same battles. But the more aware artists are of that fact, the better the odds that they can find a way to emerge victorious in a digital setting—or, at the very least, survive.

[Current Affairs | artnet News]

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: changing your scenery is pointless if it’s the only thing you change.