Have you ever wondered what your rights are as an artist? There’s no clear-cut textbook to consult—but we’re here to help. Katarina Feder, a vice president at Artists Rights Society, is answering questions of all sorts about what kind of control artists have—and don’t have—over their work.

Do you have a query of your own? Email [email protected] and it may get answered in an upcoming article.

Last summer I designed and sewed an original outfit for an artistic photo shoot involving my friend who is a model and another friend of ours who is a photographer. Imagine my surprise when I recently learned that a small gallery brought the resulting photograph to Art Basel Miami Beach, where it sold for $35,000! My outfit wasn’t “fashion,” per se, but I feel it contributed to the work. Am I entitled to any of this money?

Probably not, for reasons that may infuriate you.

The purchaser of this photograph didn’t buy the model, the outfit, or the abandoned Massachusetts mental institute where your scoundrel of a collaborator probably staged this photo shoot. (So cliché!) The collector bought only the photograph, which has just one author and one copyright owner.

Your case has something in common with a recent one brought against Jeff Koons involving his infamous “Made in Heaven” series of 1989, which consists in part of photographs in which Koons is having graphic sex with his then wife, the Italian porn star Cicciolina. In December, Koons was sued by the sculptor Michael Hayden, who made the serpentine surface on which the couple copulated, and apparently only found out about this series in 2019.

The defense’s latest dispatch in this case argues that the stony bed of snakes is not an artwork, but instead a “useful article” not protected by copyright. Koons is probably the most-sued artist of all time, so it’s no surprise that he has good lawyers: this is a shrewd argument. A “useful article,” per the government, is “an object having an intrinsic utilitarian function that is not merely to portray the appearance of the article or to convey information. Examples are clothing, furniture, machinery, dinnerware, and lighting fixtures.”

A 2017 decision involving cheerleading uniforms (with some fun-sounding amicus briefs by cosplay enthusiasts) set a new test for “useful articles,” but stipulated that in order to be eligible for copyright, the design needs to be able to be separated from its “utilitarian” functions, like covering a body. So you can copyright your original pattern of chevrons and zigzags, but not the clothes or the outfit. Since we’re discussing a get-up made for a photo shoot, I worry you might not have much of a case.

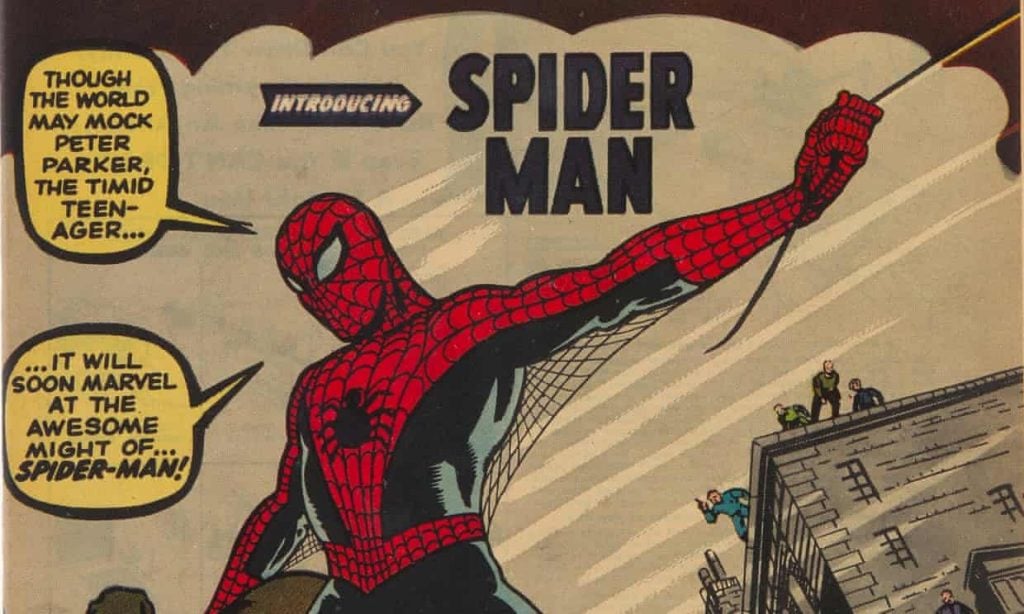

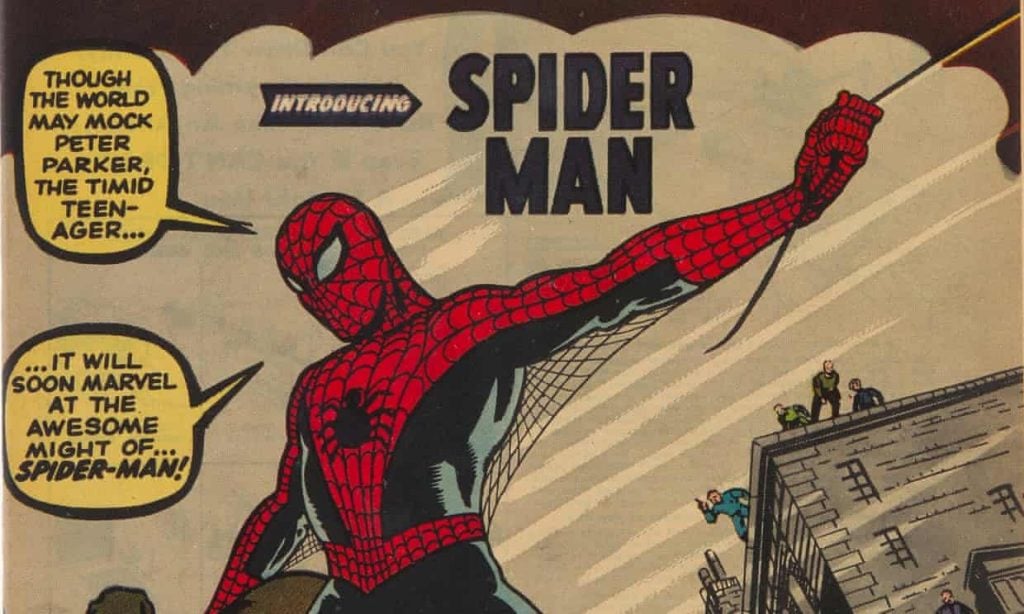

Spider-Man in his first appearance in Amazing Fantasy #15 in 1962. A

copy sold for $3.6 million at Heritage Auctions in September 2021 to set a comic book auction record. Photo courtesy of Heritage Auctions.

You recently pointed out that there are thousands of Spider-Man NFTs that seem to exist on NFT platforms with the approval of—or, I guess, without the disapproval of—the people who own the Spider-Man copyright. But what would happen if one day they decided they did care? Could they order the destruction of the NFTs?

Let’s start on a fun note. It is true that a judge may order the destruction of property that has been “made or used in violation of the copyright owner’s exclusive rights,” such as “plates, molds, matrices, masters, tapes, film negatives, or other articles by means of which such copies or phonorecords may be reproduced.” This makes sense: if you’re busted for hawking unlicensed Bart Simpson T-shirts, the judge wants to make sure you won’t make any more of them after you render unto Disney your misappropriated funds.

We do this with artworks, too, but we call them forgeries—and if they’re not destroyed, they often end up back on the market. With NFTs, though, the matter becomes vastly more complicated. This year has already seen a number of cases that may help determine what the rules are going forward. Both LVMH and Nike have sued NFT creators alleging trademark infringement. The creator of the so-called MetaBirkins claims that his virtual bags do for Hermès what Andy Warhol did for Campbell’s Soup…which is an, er, ambitious defense, since I can’t think of a single way in which the two situations are similar.

To return to your example of the Spider-Men, a Sony lawsuit would mean costly and expensive litigation for the offending creators. For the buyers of these unauthorized NFTs, if Sony did pursue high-profile legal action or issue their own authorized Spider-Man NFTs, that would probably crater the value for the old, off-brand ones.

In short, to all NFT buyers out there, I would say: Be aware of the provenance, and if it’s not the real thing, pass on the purchase.

Jason Momoa attends the Dune UK Special Screening at Odeon Luxe Leicester Square on October 18, 2021, in London. Photo: Mike Marsland/WireImage.

I know we’re all laughing at the Spice DAO people, but why, exactly, weren’t they able to follow through with their business plan? How did they get so far before they realized that it wasn’t viable?

Laugh we did. While I do my best to maintain a certain level of IP decorum, it’s hard not to call this snafu on the part of the Spice DAO anything but silly.

A DAO, or a decentralized autonomous organization, is akin to a venture capital fund meets a Stalinist members-only club, with a crypto twist. DAOs are both automated and decentralized. There is no board of directors or CEO calling the shots. Instead, governing rules are embedded into the code, with decisions reached by consensus and implemented programmatically.

DAOs first made headlines in 2016 when the DAO for a German startup, slock.it, creatively named “The DAO,” was allegedly hacked to the tune of $50 million in Ethereum. Although the hack was made possible by slock.it’s faulty code of and not the underlying blockchain technology, there was a subsequent fallout, and DAOs were relegated to the fringes of crypto culture. Until recently…

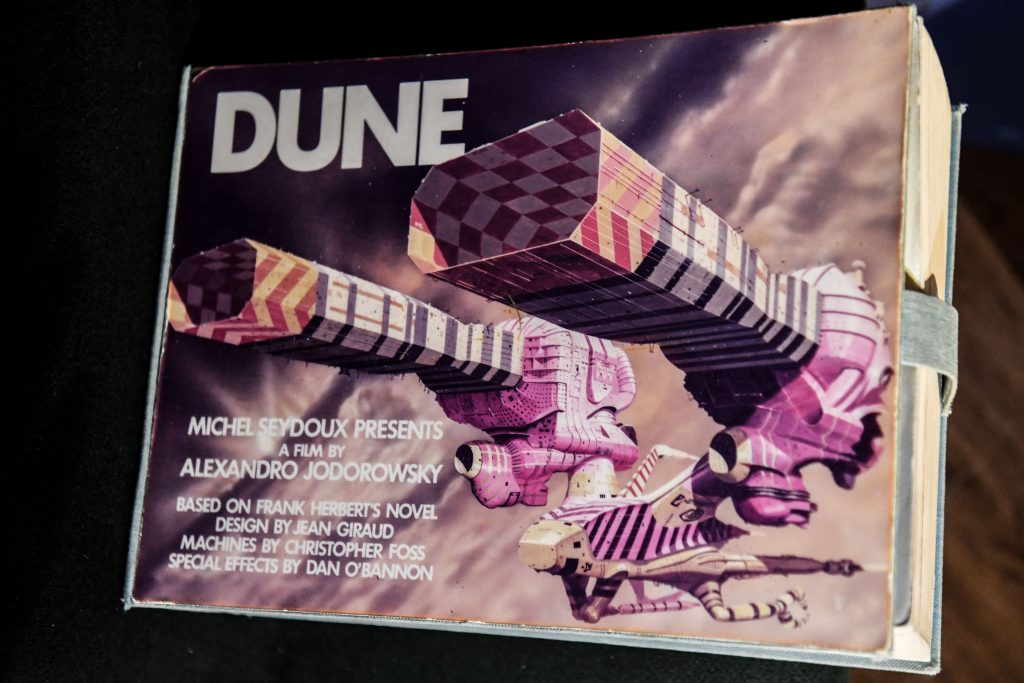

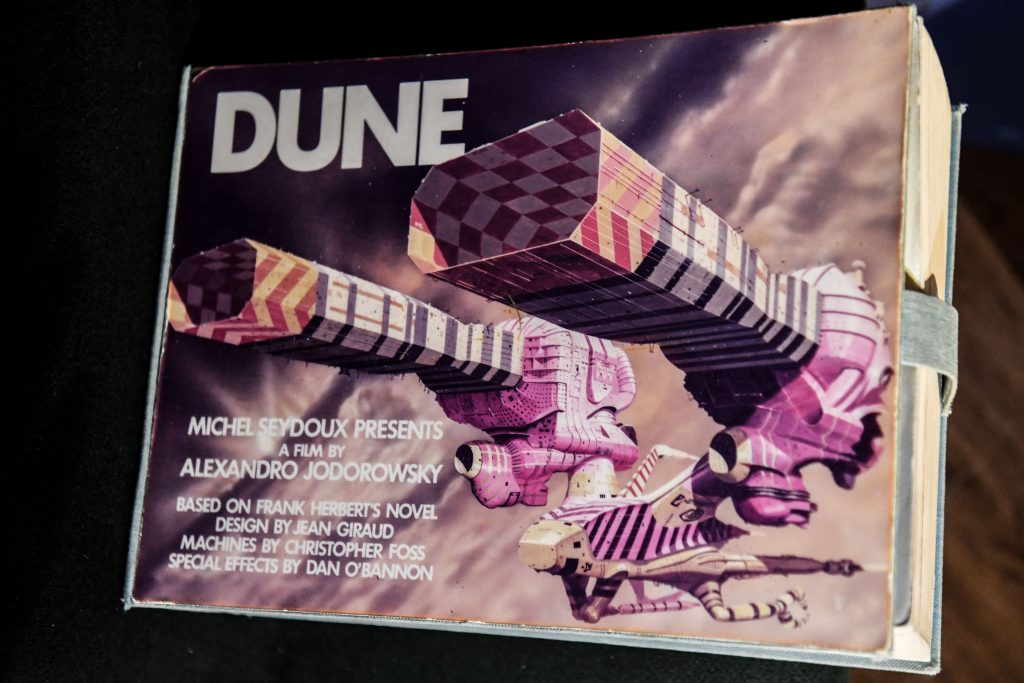

Which brings us to the Spice DAO (“Site Under Construction…”), which made its organizing mission the liberation of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Dune, the experimental filmmaker’s planned adaptation of Frank Herbert’s 1965 stoner sci-fi epic novel. Denis Villeneuve is currently enjoying quite a bit of Oscar buzz for his adaptation of the book that came out last year, but Jodorowsky’s film was set to be even trippier, with Salvador Dalí slated to play the emperor of the galaxy. Alas, the film’s producer died in 1973 before the movie could be made, leaving the world with nothing more than the sketches and storyboards Jodorowsky produced with French comic book artist Jean “Moebius” Giraud.

One of the ten copies of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s epic 1970 Dune storyboard, featuring illustrations by Moebius and H.R. Giger, on display at Christie’s Paris, November 19, 2021. Photo: ALAIN JOCARD/AFP via Getty Images.

When a book of the drawings came up at Christie’s in November, Spice DAO paid $3 million—roughly 100 times the market estimate—to procure the book with the stated aim of using its IP for the production of NFTs, as well as its characters for the creation of an animated television show.

If this sounds nonsensical to you, that’s because it is. As any reader of this column could tell you, the purchase of a physical object has absolutely nothing to do with the rights to use the underlying copyright, first editions be damned. Now it’s $3 million later, and the Spice DAO has the same claim to the rights for Dune’s IP as they would have if they’d walked into McNally Jackson and bought a copy of the novel for $15.99.

How this could happen is really anybody’s guess. It has been speculated that this was simply a PR stunt, but for $3 million? Unlikely. More likely, I would think, is that the autonomous structure of a DAO makes it easy for participants to miss the big picture. With no one officially at the helm, there’s no one to take the blame, no figure of authority to have second thoughts and read the fine print in the auction catalogue. Hopefully they kept a few bucks for some Spice…

The Aboriginal flag, created by Harold Thomas in 1971, is projected onto the sails of the Sydney Opera House during the Australia Day Live concert on January 26, 2022. Photo: James D. Morgan/Getty Images.

I was heartened to hear that the Australian government recently purchased the copyright for a new flag that celebrates its Indigenous people. I was slightly disheartened, however, to learn at the same time that flags can be copyrighted in the first place. What could be the purpose of that?

Yes, flags are protected by copyright. And why shouldn’t they be? Copyright, by definition, protects all “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which they can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device.” Does this not describe the American flag, an original work with its own author and organizing ideas? Even the Jolly Roger is said to have its own progenitor in Emanuel Wynn. Though that probably wasn’t the kind of thing you could sue someone over, since everyone involved would have been, you know, a literal pirate.

Since copyright in the United States (and most other countries, including Australia) covers the life of a creator plus 70 years, most flags wouldn’t still be subject to copyright laws. But the Australian flag in question, generally known as the Aboriginal flag, was created by Harold Thomas in 1971 for a march, and recognized in 1995 as one of the country’s official flags. But, as we often like to remind people in this column, it’s rather difficult to separate a copyright from its creator. In 2018 Thomas gave the flag’s reproduction rights to WAM Clothing, who promptly started suing the well-meaning people who put it on dresses and T-shirts. Perhaps realizing his mistake, Thomas has just now sold the copyright to the Australian government—though not, of course, before minting an NFT of it.

Copyright isn’t the only protection offered to flags, as other newer offerings, like the Olympic flag, tend to be shielded by international agreements. In 2007, Johnson & Johnson even attempted to sue the Red Cross over alleged trademark infringement, which was about as successful as their initial Covid-19 vaccination rollout (I kid! Sort of. Proud J&J vax card holder.).

Gilbert Baker, the man who created the rainbow LGBT flag, has always renounced any rights to it, because he wanted it to fly freely. You asked about the purpose of copyrighting flags, but I think that misunderstands the nature of copyright. It’s not something that you need to apply for or seek. It’s something that the law imbues in a unique work from the moment that it’s completed. Its only real purpose is to protect the creators’ vision, because they tend to be its best stewards.